Woodborough’s Heritage

An ancient Sherwood Forest village, recorded in Domesday

Woodborough Male Friendly Society - by Peter Saunders

A Friendly society had been enrolled in Woodborough in November 1794 having 71 members by 1803 and is believed to have met at the Four Bells. There were 108 members of friendly societies living in Woodborough in 1813, 110 in 1814 and 115 in 1815. It seems likely that all these would have been members of the village friendly society, though not necessarily so. For some reasons unknown, this society appears to have ceased to function sometime between 1815 and 1826.

A branch of the Nottingham Ancient Imperial United Order of Oddfellows began in 1843, formed by members of a former sick club, probably the above friendly society, but transferred to the Gleaner public house at Calverton shortly afterwards.

The Woodborough Male Friendly Society, whose records are the subject of the following account, began in 1826 and was first enrolled in 1827. It is recorded as meeting at the Punch Bowl Inn in 1876 but later moved to the Four Bells – the Punch Bowl closed in 1907.

A public house would not, one would suppose, have been the most suitable place for a friendly society composed mainly of devout non-conformist framework knitters to meet. Probably the availability of a suitable room for meetings left them little choice.

Admission for membership of the Woodborough Male Friendly Society was open to men over the age of sixteen but not over thirty one. Of 620 plus admissions in the Society’s registers the ages on entry of 403 is recorded, the average age being 21. Applicants had to provide a medical certificate confirming their fitness, and a ballot of members at the monthly meeting was held, a majority in favour being necessary to decide if the applicants were fit persons to be admitted as members.

There does not seem to have been any rule that membership was only open to residents of the village. Members are recorded as living in neighbouring villages such as Calverton, Epperstone and Burton Joyce, further afield at Selston and Beeston, and as far distant as Doncaster. However it would seem, judging by their names, that these were probably members who had moved away from the village due to marriage or employment, but had continued their membership of the Society.

An entry payment had to be made by new members usually in two instalments, the second being required by the end of the first 6 months of membership. The entry fee in 1827 was 5 shillings, had risen to 7 shillings and 6 pence by September 1843 and in March 1884 it was 7 shillings and 8 pence, with two payments of 3 shillings and 11 pence and 3 shillings and 9 pence. After 1891 it reverted to 7 shillings and 6 pence but by the 1922 rules it varied from one shilling for those under 17 to 15 shillings for those aged 30. A monthly subscription of one shilling was also payable by members throughout the history of the Society. Stock to the value of £3 was purchased during or at the end of five years membership and in 1837 it was agreed that those with less than 5 years membership should pay a deposit of £1 10s towards the £3 of stock. In the 3 years 1829-31 inclusive the value of stock was £57 8s 5d, £60 0s 0d and £56 14s 0d respectively.

Subscriptions/funds in excess of a small amount of cash in hand were deposited in the savings bank. Early entries show deposits of £15 in 1829, 1833 and £25 in 1834 with interest of 14 shillings and 3 pence in 1828. There are occasional entries for ‘going to the bank 6 pence’ – would this have entailed a long walk from Woodborough to Nottingham and back? – perhaps the 6 pence was to make up for lost wages through the journey. When there was a lack of ‘cash in hand’ for the payment of sick benefit, loans were sometimes made by one of the local publicans.

The amended rules of the Society dated 1922 show that the Society was enrolled with the Registrar of Friendly Societies in 1827 and the rules would have been drawn up and printed with the approval of the Registrar.

The objects of the Society were threefold. To provide

(a) Sick benefit for its members during sickness or other infirmity.

(b) Medical benefit for members and their wives.

(c) Funeral benefit for members and their wives.

Incidentally members only received funeral benefit for their first wife, nothing for second or subsequent wives. None of the above benefits were to be paid until a member had contributed for 18 months. There was no benefit for unemployment, so in difficult times, when trade was poor and prices low, it was a question of work or starve, and in framework knitting this work involved the whole family, often including children as young as 6 years of age. This may have been one of the reasons that the Society purchased land with its surplus funds so that members could rent a ‘Club piece’ to provide some food in times of depression.

The Society’s officers consisted of a secretary, treasurer and two stewards, and the management of the Society was undertaken by them, together with five committee men and three trustees.

The position of Steward seems to have been an onerous one. It was they who received members contributions at the monthly meetings and they who were required to pay out benefits to members, giving an account of their transactions at each monthly meeting. A Steward also had to visit every week each member living in the parish receiving sick benefit to ensure he was not malingering, visiting the public house, earning any money or away visiting, the latter allowable only with the Medical Officer’s permission. It is to be hoped that a Steward was appointed for each half of the village as, with as many as 38 members receiving benefit in some winter months, a journey in snow from the foot of Bank Hill to the far end of Shelt Hill distributing benefit would have been an arduous task. For this work the Steward received an annual remuneration of 15 shillings in 1878 rising to £1 14s by 1918.

From the 1922 rules it appears that the Secretary was responsible for the keeping of the account books. However, the duties of the Secretary were so numerous that the accounts for the member’s monthly subscriptions for the benefits paid out and for the very occasional fines for breaking Society rules were kept by two book-keepers as annual payments were made to them for this work. Joseph Hucknall and Thomas Leafe, both framework knitters, were paid six shillings each in the years 1849 and 1850. By 1907 the book-keepers’ salaries had risen to £1 2s for the year.

At this time the Secretary and Treasurer received annual salaries of £1 12s and ten shillings respectively. Considering that the Officers and book-keepers had probably received little or no formal education in the early years of the Society they seem to have managed very well. Perhaps as the majority were framework knitters they had to be fairly astute financially to organise their own little family ‘business’.

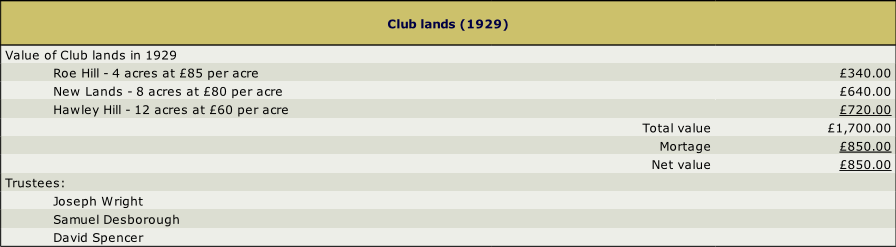

The Society’s rules were regularly revised, amendment being recorded on at least 8 occasions between 1827 and 1953. Unfortunately the names of the Trustees are not mentioned as such in the account books but it is recorded elsewhere that Joseph Wright, Samuel Desborough and David Spencer were the Trustees in 1908 and the same names also appear in the 1922 rules with John Clayton as secretary.

The Society’s accounts had to be audited at least once a year, but the first mention of auditors in the account books occurs in 1890. Elijah Wright was an auditor for most years from 1890 to 1910, first with William Hogg and then Joseph Clayton. After 1910 Joseph Clayton continued as an auditor with headmaster John Gee from 1911 to 1917 and then with headmaster A.W. Saunders who was still an auditor in 1951.

The Society’s rules state that a Qualified Medical Practitioner should be appointed, becoming either a benefit or honorary member of the Society. He was to attend all sick members and their wives within a 3-mile radius of the Society’s registered office providing them with proper and sufficient medical and surgical care and the necessary medicines during sickness. The Committee and the doctor would agree to the latter being paid a certain sum for each member and wife contributing to the Medical Aid Fund. The 1922 rules stated that each member must contribute one shilling per annum towards the doctor’s salary. The doctor was to be the sole judge of the necessity for placing a sick member on, and declaring him off, the sick fund of the Society.

As the medical aid and sick benefit were two of the three main aims of the Society, limited to those living within a 3-mile radius of the Punch Bowl*/Four Bells public houses, this virtually excluded non-residents of the village from the Society’s benefits.

* The first registered office was at the Punch Bowl and then the Four Bells.

As all members had to be under 31 and provide a certificate of good health on joining the Society, it is not surprising that for a number of years after the Society’s formation the doctor’s annual fee paid half yearly, was small, under £7 until 1850. As the age of founding members increased, and as the Society grew, so did the doctor’s annual remuneration. By 1877, when membership was about 170 and founder members would be aged between 66 and 81, the doctor was receiving about £24 a year. In the census year of 1881 a total of 51 members received sick benefit. The doctor would have had to see each sick member at least twice to sign him on and off, including perhaps intermediate visits and prescribing medicines, so that the £28 18s 9d he received for that year would appear to have been well earned. From about 1884 to 1900 the doctor’s salary varied between £30 and £35 a year, coinciding with peak membership of approximately 210.

The purchase of property on the north side of Netherfield Lane (Lowdham Lane) called the New Land, one grass field 3 acres 3 roods 39 perches and one arable field 7 acres 3 roods 38 perches for a total cost £943. Re-sold the grass field to Mr Roby Liddington Thorpe for £314,

February 23rd 1891 – John Clayton, Secretary.

By 1913 membership had dropped to about 150 and the doctor’s salary to about £22 and by 1947, after the passing of the National Health Act, and with membership of about 80, the doctor received less than £8 per annum.

The first purchase of land by the Society occurred in 1841 with the entry ‘May 3 1841 for land £18 6s 3d’. Half yearly interest to Southwell amounting to £3 10s starts in 1842 as well as entries for Land Tax, so it would appear that the main money for the purchase of the land was borrowed from Southwell and the sum of £18 6s 3d above was a deposit. The annual interest of £7 at roughly 4% would value the land at approximately £180. Rent for the land presumably from the ‘allotment’ holding members stood at £4 4s 4½d in September 1843 and expenses occurred in managing the land began to appear in the accounts. Items such as mending the gate, one shilling and sixpence, August 1844; hedge knife, three shillings and eight pence, May 1845; new gates, drainage, cutting the hedge, fencing, keys and locks occur.

In January 1856 more land was bought, a deposit of £26 10s was taken to Southwell. A mortgage on this land was immediately taken out and the half-yearly interest increased to £17 giving the impression that the total value of land held was approximately £850. In April 1856 the Society carried out improvement work on this land with bills for measuring, ploughing, mowing, drainage tiles, hedging, ditching, mending fences, gates, locks and keys.

A piece of land was evidently retained for Society use, i.e. not divided into allotments, and cultivated on the Society’s behalf, mainly for growing potatoes and barley. In July 1858 the sum of four shillings and sixpence was paid for potatoes to be hoed and in 1859, a winnowing machine, riddle, sieve and a barley chopper, fork and skep were purchased for a total of £5 5s 8d, four shillings was paid for the harvesting of the potatoes.

There was either a barn on the Society’s land in need of repair, or one was constructed, as there are bills for bricks, tiles and lime, a bill for the barn floor and one paid to Mr Patching, a village builder. Further work on the land with bills for drainage work, pipes, carting the drainage pipes and repairing the gateway occurred in November 1861 and January 1862.

Land rent was collected at the monthly meetings from members, amounting to £30 12s 5d in 1864. After 1865 references to land in the general accounts book ceased, presumably to be kept in a separate account book, now unfortunately lost.

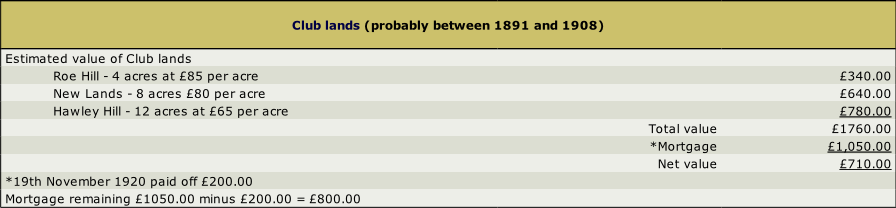

In 1891 a third piece of land was purchased for £943, part of which was immediately resold for £314 perhaps because it was unsuitable for the type of market gardening/agriculture practised by the members. The purchase brought the total land mortgage to £1050. A round sum, beginning in 1888, was transferred from the Land account to the General account. This varied from £20 in 1888, £27 in 1921 and £40 from 1937 onwards with £50 in 1944 and 1945.

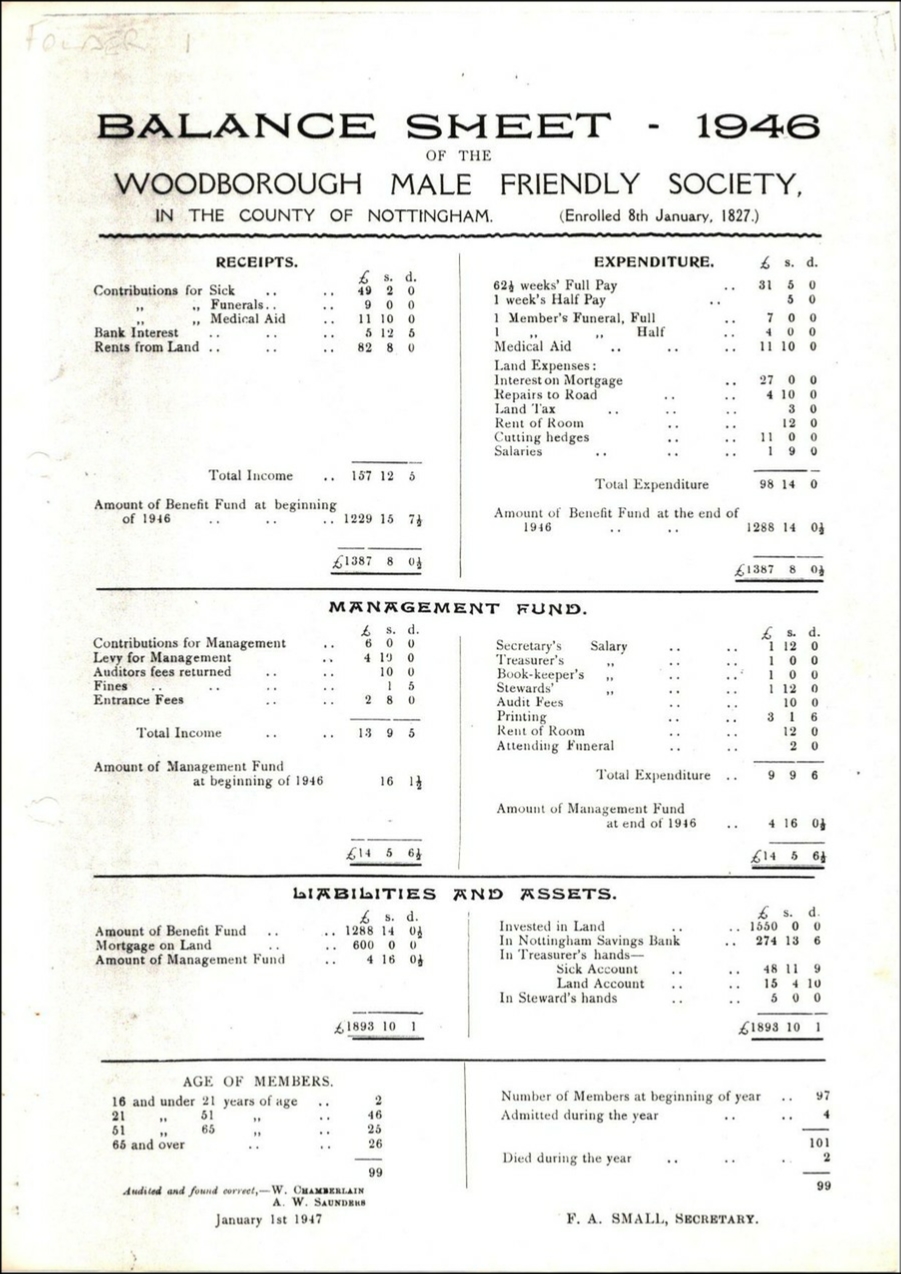

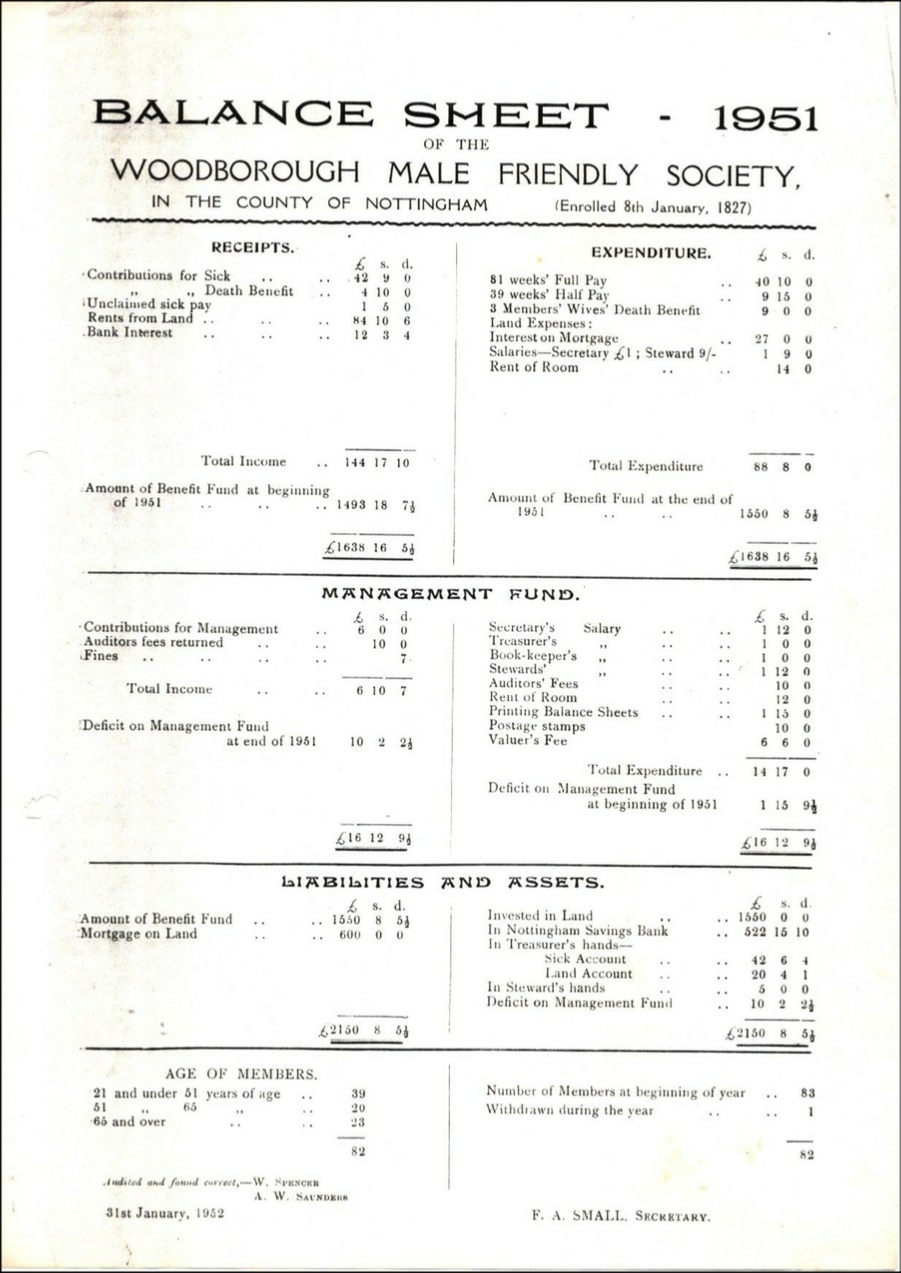

The assets of the Society had to be valued every five years. The 1929 valuation showed that the Society had 24 acres of land, worth £1700 with a mortgage of £850. By 1946 the mortgage had reduced to £600 and remained at that figure until at least 1951 with mortgage interest charges of £27 per annum.

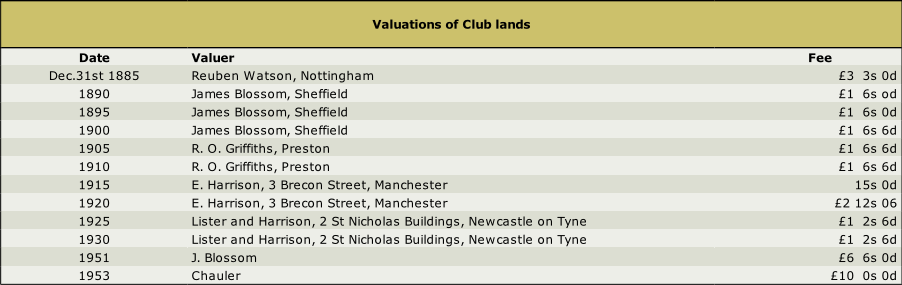

The balance sheets of 1946 and 1951, income from rents for the land amounted to £82 8s and £84 10s 6d respectively. The valuers were not always local people, from 1885 onwards they were from Sheffield, Preston, Manchester, Leamington Spa and Newcastle on Tyne, as well as from Nottingham.

As some allotment holders were agricultural labourers their employers would lend horses and plough for the allotments to be ploughed ‘en masse’. On occasions Mr A.W. Saunders, headmaster 1916-1950 at the Woodborough School, who possessed a Gunter’s chain, would be asked to go and mark out the allotments after ploughing.

Because the Society held land they presumably had to contribute to the rates of the parish. There are a number of references in the accounts to Land Tax, Poor rate, Church rate and Highway rate at a time when the Churchwardens and Overseers of the Poor were responsible for looking after the parish needy and the village was responsible for maintaining the roads within its boundaries. Entries such as these occurred between January 1843 and June 1865:

August 1845, Poor rate and Church rate 8s 1d

December 1848, Land, Highway and Poor rate 6s 9½d

Although a membership admissions list occurs for the Society, and also a list of funerals benefits paid to members or their families, there are only four lists of members at different times. These occur in 1826, 1888, 1907 and 1935. However, using the monthly subscription receipts as a guide, it is possible to arrive at an approximate membership total for other periods in the Society’s history.

There are two lists for 1826, one list gives 47 paid up members, but most of these names occur again in a second list of 30. Admittedly they could have been ‘family’ i.e. nephews or sons with the same Christian names.

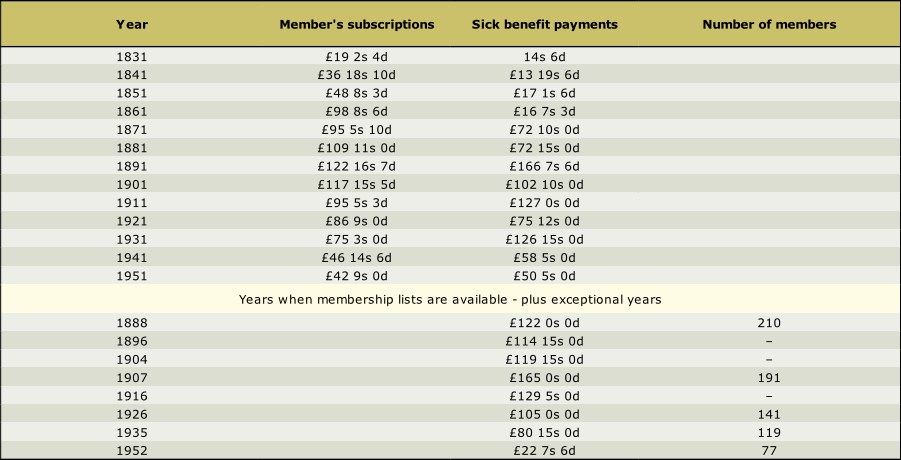

In the first few years after 1826 recruitment was slow with an average of 3 or 4 new members joining annually. There was an unusually high number of new members, 15, in 1835, but for the next 15 years an average of 4 or 5 new members joined. The greatest rise in membership was during the three decades following 1850, 1860 and 1870 with 74, 73 and 80 respectively so that by 1888 there were about 210 members. Recruitment continued with about 55 new members in each of the two decades between 1880 and 1900, but after this the number of annual admissions steadily declined so that after 1910 there were only 2 or 3 each year. By 1907 the membership stood at 191, fell to 141 in 1926, 119 in 1935, 108 in 1941, 84 in 1945 and in 1952, the year before the Society was wound up, membership had dropped to 78.

The ‘Club Feast’ was the highlight of the year, according to witnesses still living in the village in 1989, who remember the event. It took place on Whitsuntide Tuesday and according to the 1886 rules every member was expected to be at the Club Room by 9 a.m. and from there to process to Church or Chapel to hear Divine Service. By 1922 the Rules merely stated

‘The anniversary of the Society may be held on Whit-Tuesday in each year. No part of the expenses of the anniversary shall come out of any of the funds. Attendance shall be voluntary’.

Those who remember the Club Feast in its heyday recount how members processed, the band would start playing commencing on Shelt Hill leading to Shelt Hill Farm where the band played a requested tune for the occupant. Returning to the New Inn [closed in 1927], they sampled their first liquid refreshment before continuing to the Nag’s Head for about an hour. They arrived at the Four Bells Club Room in time for lunch and then proceeded up the Main Street to Thorneywood where for an hour the band supplied music for the dancers on the tennis courts. Retracing their steps to the Hall, another hour would be spent dancing on the lower lawn, down as far as Johnny Ball’s shop – he was an officer in the Society, and onto the Manor, after which they returned to the Band Room and dispersed. No doubt between 1827 and 1922 refreshments would have been supplied at the Cock and Falcon (closed c 1864), the Punch Bowl (closed 1907), and the Bugle Horn (closed 1922), as their licensees/beerhouse keepers are recorded as having given donations towards the Feast. Is it any wonder that the day had been described ‘a proper boozy affair’? It would also appear that a collection to defray expenses was made en route and in 1863 raised the sum of £7 6s 5½d. This, with gifts that year, raised a total of £10 15s 5d which covered more than half the expenses of the Feast.

Occasionally the bills for the Feast expenses were itemised as in 1843 for mutton, cheese, mustard, pepper, lettuce, cabbage, bread and sugar, together with Mr Wood’s bill and Mr Clay’s, probably for meat and potatoes. Together with the cook’s bill of 2s 6d, the total came to £4 2s 6½d, less than half the 1840 bill. By 1855 the amount spent on the Feast had risen to £11 13s 1d, to include bills for meat, cheese, potatoes, cauliflower and an item for bread and baking to Mr James, the village baker. The band’s fee of £1 10s was included in the total. In 1865, the last year when expenses for the feast were recorded, the bills had risen to £24 7s 4d. Perhaps we can judge the amounts consumed from bills of 10s 6d for 12 pecks of potatoes (150 lb in 1863), 10s 6d for milk and £10 3s 4½d for meat in 1864. These were considerable sums at a time when sick benefit was only nine shillings per week.

The costs of the Feast were offset by donations from the local gentry, and also to a lesser extent by the village’s publicans and shopkeepers, who no doubt recouped their gifts, and much more, by supplying goods for the Feast and liquid refreshment for members on their promenade through the village. Although most of the members probably paid for their own ale on their walk, there is an item in the 1859 Feast accounts to Mr Gadsby for ale £3 11s 3d. This was probably consumed at the sit down meal as John Gadsby was the Licensee of the Four Bells at that time and had made a donation of five shillings to the Feast’s funds.

Instead of the Feast in the years 1830 and 1835 a Christmas supper was held. The expenses for these are entered in January 1831 for £2 1s 10d and December 1835 £2 5s 11d. These must have been modest affairs compared with the Feasts but at the time the Society would be still quite small. Also on two occasions there appears to have been a Christmas share-out. In January 1839 is an entry ‘Paid to members £9 2s’ and in February 1842 ‘Divided among the members £3 0s 0d’. The last Club Feast, according to Mannie Foster, was held in 1931.

From the beginning of the Society there is an entry for ‘Shot’ as an expense at each monthly meeting. J. O’Neill suggests that this may have been a synonym for ale, particularly as the meetings were held at a public house. An alternative meaning may be ‘refreshment’ or ‘snap’ as used by the local mining fraternity. Shot was by no means a small item of expense, although the amount spent on it each meeting varied considerably over the years. From 1827-1830 it was about 6s 6d, from 1831-3 it was 5s plus. By 1836 it had risen to 7s 6d. Perhaps they had a good summer weather-wise in 1839 when the August and September amounts were 12s 6d and 9s 2d respectively. It levelled off at about 8s 4d until 1848 when it was reduced to just one or two shillings.

When one considers that sick benefit was only seven shillings a week for a man and his family at this time, many husbands would probably have been subjected to harsh words if their wives had known the amount spent on refreshment, liquid or otherwise, at the monthly meetings. One wonders how many of the then members attended the committee meeting in 1856 when 5s 6d was spent on shot!

Shot was also recorded after the funeral of a member(1). In the 1886 rules one of 13 chosen members was in rotation, to attend the funeral of a member residing in the Village. In the 1922 rules, two officers of the Society were to attend. It seems that often other members of the Society also attended and funeral ‘shot’ varied from 3s 3d in 1830 to 4s 10½d in 1847. After May 1855 until entries for shot ceased in 1866, the average amount for funeral shot was 4s 3d. Whether different book-keepers referred to ale as shot is difficult to determine as an item in March 1854 reads ‘ale for Thomas Leafe’s funeral 2s 11d’ and in June 1861 ‘for shot and ale at other times 7s 3½d’.

Source: 1. J. O’Neill

Although the Officers and members of the Woodborough Male Friendly Society must have been aware that it was illegal for the Society to spend their money on social activities, one wonders what must have happened in 1866 to have brought their recording of expenses on the Feast and Shot to such an abrupt halt. After a long period under which shot may have been concealed under the heading ‘Expenses of Management’ usually for a similar amount, ‘refreshment’ appeared again in 1897 at an average of about one shilling. However, in February 1900 there were five members’ funerals and in the following May there were four more with ‘refreshments’ costing 18s 5d and 14s 6½d in the two months. Perhaps having suffered on a cold February day at the windswept Woodborough cemetery they needed something to keep out the cold.

A band, possibly the Woodborough Village Band, existed as early as 1829, for in that year ‘the Band’ was paid one guinea for performing on Club Feast day. The Band continued to play annually at the Feast, for what would a procession be if it were not led by a band. It’s fee rising to £1 10s by 1853 and £2 10s in 1865, the last year in which Feast expenses were recorded. Collections on Feast day nevertheless occurred until 1883.

As the great majority of Society members were framework-knitters, so probably were members of the band at that time. The Reverend Buckland in his ‘History of Woodborough 1896’ gives the names of a number of instrumentalists, string, brass and wood-wind who accompanied the church choir. The 1841 and 1851 censuses confirm that they were all framework-knitters who were mainly Non-conformists and were instrumental in founding the Wesleyan Methodists, Primitive Methodists and Baptist chapels in the village between 1827 and 1851. Perhaps the church services provided them with a weekly performance as a band. The Band(1) in itself would be quite an attraction as a reference to the anniversary feast of the Ancient Order of Foresters Court Good Intent at Kneesall 27th June 1845 notes “The brethren walked in procession to the church preceded by the Woodborough Band dressed ‘á la militaire’.”

Source: 1. J. O’Neill

Although there are no references to uniform or a Club banner, there is a bill of June 1884 of £3 16s 5½d for thirteen sashes. It appears that according to memory black sashes were worn by Society Officers when attending the funeral of a member.

It is difficult to know which benefits of the Society its members valued most. When the Society began the sick benefit was set at 7 shillings a week, not much to feed and clothe a family but the average wage of a labourer at that time was about seven to ten shillings per week. The Society’s articles were altered in August 1843 raising the sick benefit to 9 shillings a week and in 1865 it was increased to 10 shillings where it remained for the next 88 years until the Society ceased to function in 1953.

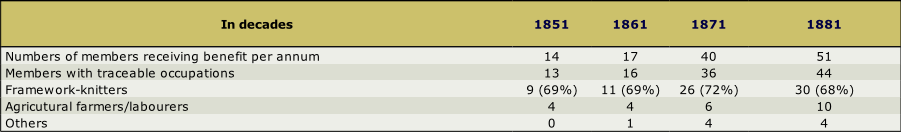

Who were the main beneficiaries? Undoubtedly the village framework knitters who formed a majority of the Society. In the five census years 1841 to 1881 inclusive 35 members joined the Society, 33 being Woodborough inhabitants, 23 of the 33 were framework knitters, 6 were either labourers or agricultural labourers and the remaining four were tradesmen/craftsmen. In both the years 1835 and 1856 there were unusually high numbers of new members, 15 in each year. Of the 1835 entrants, the occupations of 11 can be traced and eight of them were framework knitters. Only one person’s occupation in the 1856 group could not be traced and 12 of the remaining 14 were framework knitters.

Of those members receiving benefit in the census years whose occupations were traceable the following table can be drawn up.

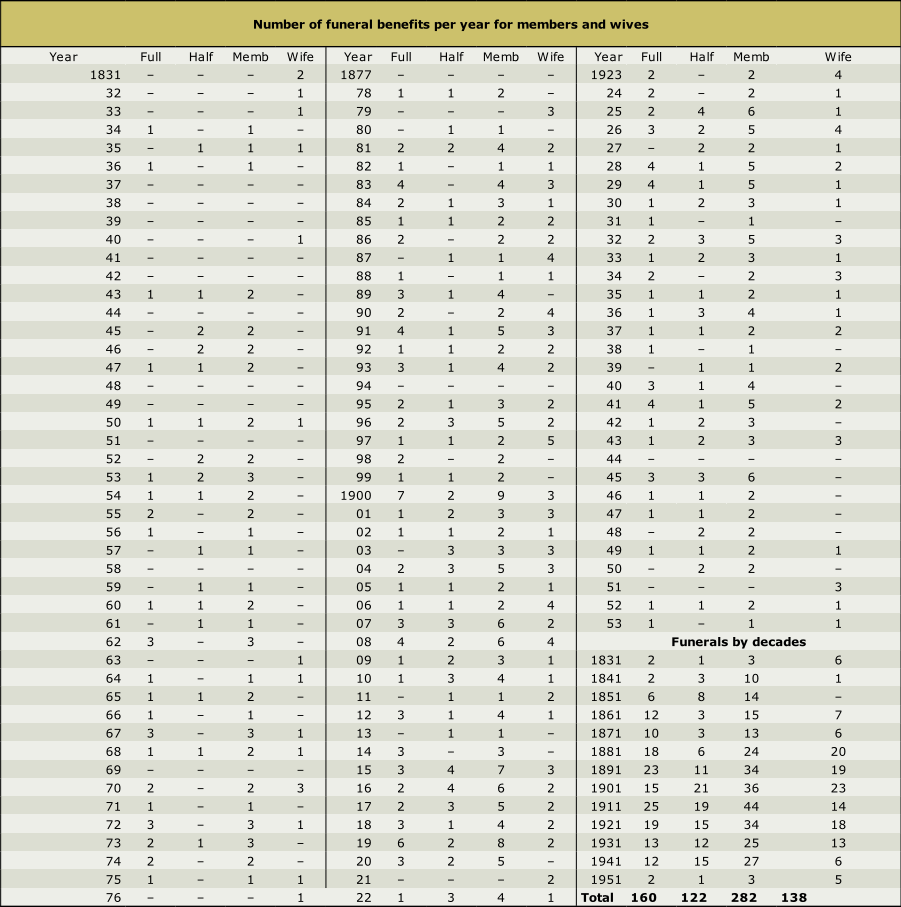

In cases where no claim was made for benefit the member was buried by the Society ‘in a decent manner’ and any surplus was returned to the fund. During the period November 1859 to July 1860 four members received 16 shillings each for a child’s funeral but there is no explanation in the accounts for this unusual procedure. Members were required to pay an additional shilling on the death of a member and six pence on the death of a member’s wife.

A record was kept each month in the accounts of the disbursement of sick pay. According to the rules current at the time members were allowed a number of weeks, usually 15 on full pay and thereafter another 20 weeks on half pay. At one period as in the 1886 rules, they were allowed one quarter pay for the remainder of their sickness. This latter could have been open to abuse as it was ceased in May 1894 when the rules were again revised. A member who had received sick benefit could not claim full benefit again until 18 months after he had ceased to benefit previously. If he declared within 18 months his illness was regarded as a continuance of his previous illness.

The number of sick payments to members varied considerably from £41 5s to 38 members in February 1900 to £2 10s to just two members in July 1894. The largest payments were usually for the months of December to April but 1891 and 1911 seemed to have been exceptional years with large payments in June and July, perhaps due to an epidemic.

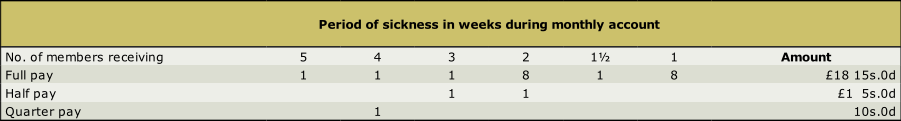

The following table shows the payments for March 1890 of £20 10s.

Another advantage of being a Society member was access to an allotment or ‘Club piece’. Some of the framework-knitting members had a garden attached to the property, many did not. The land purchased by the Society over the years enabled members to grow enough vegetables for their family’s needs and the land cultivated on the Society’s behalf probably provided potatoes and barley for those members having the facility to keep a pig.

In what was an agricultural environment, those framework knitting members would have been familiar with the practices of their neighbouring agricultural members, if they were not gardeners already. As mentioned by J. O’Neill this agricultural experience proved most useful when the framework-knitting industry started to decline, many turning their hands to intensive market gardening, their produce finding a ready market in Nottingham where it was taken by the local carrier’s carts.

The fact that the majority of the Society’s members for most of its existence were non-conformist framework knitters must have meant that there were close bonds between them in this otherwise agricultural community. Although there is no suggestion whatsoever in the records that the Woodborough Male Friendly Society was in any way a trade or political organisation, the regular contact it afforded both its framework-knitting and agricultural members must have kept them abreast of trends in their occupations, and as many of the same frame-workers’ names occur in neighbouring villages through inter-marriages, information on the trade would not just be confined to Woodborough experiences.

As the table shows, there were many years from 1888 to 1951 when sick benefits payments exceeded the subscriptions received. Money transferred from the Land Account may well have kept the Society on an even keel.

Mortality

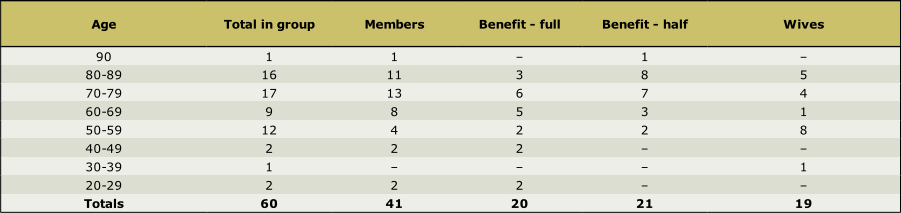

The task of connecting the admission dates of 620 plus members and their burial dates (not counting those living when the Society closed or those who had withdrawn from membership without record) proved too arduous a task but a list of 60 members and wives who died in the period July 1926-November 1938 in one of the subscription books reveals some interesting facts on the longevity of members.

The oldest member was 93 and the youngest 20. Out of the 41 members, 33 were over 60 and 25 were over 70 years of age when they died, 19 of the 33 members aged 60 or over had buried their wives. Members only received ‘half’ benefit if they already received ‘half’ on their wife’s death.

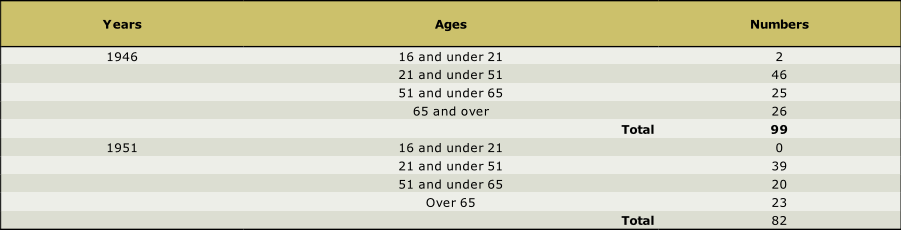

The summary of the ages of members shown on the Society’s 1946 and 1951 Balance Sheets illustrates the decline in membership, and the reluctance of young men to join in the final decade.

In order to remain solvent, the income from members subscriptions, entrance fees, funeral and medical contributions, bank interest and rents from lands had to cover all expenses. Expenses consisted mainly of sick payments, funeral payments, room hire, Officer’s salaries, doctor’s fees, and maintenance of Society land. It is a credit to the Society’s officers and members, probably having had little formal education in the early years of the Society, that over 127 years it remained viable until, with the coming of the National Health Act and the Welfare State its benefits were no longer a necessity. Even so, by 1951 the Benefit Fund had reached £1550 8s 5½d and was increasing by an average of £50 a year.

According to the rules of the Society the consent of five sixths in value of its members was necessary for its dissolution. Although the Registrar of Friendly Societies considered that the Society was still serving a useful purpose and that its funds could raise the levels of benefit, the members decided to dissolve the Society. The lands were sold and the assets of the Society amounting to £2201 18s 0d were divided among the 78 members of the Society according to the number of shares held and the mortgage also paid. So ended a village Friendly Society, run by the villagers themselves, which in its heyday had boasted over 200 members.

Finally two sets of official accounts, one for 1946, the second for 1951:

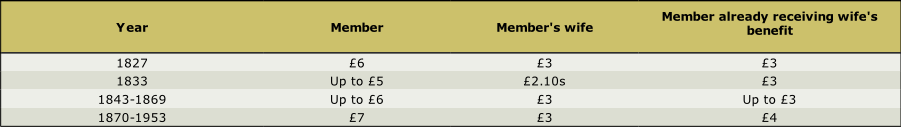

76 (70%) out of a total of 109 receiving benefits with known occupations were framework-knitters and 24 (22%) were engaged in agriculture. Out of the other 4 ‘other’ occupations in 1881 2 were beer-house keepers and one a publican. Another benefit received by members or their families was the funeral benefit. This varied during the Society’s history as follows.

Acknowledgement:

- Researched and written by Peter Saunders.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

| Navigate this site |

| 001 Timeline |

| 100 - 114 St Swithuns Church - Index |

| 115 - 121 Churchyard & Cemetery - Index |

| 122 - 128 Methodist Church - Index |

| 129 - 131 Baptist Chapel - Index |

| 132 - 132.4 Institute - Index |

| 129 - A History of the Chapel |

| 130 - Baptist Chapel School (Lilly's School) |

| 131 - Baptist Chapel internment |

| 132 - The Institute from 1826 |

| 132.1 Institute Minutes |

| 132.2 Iinstitute Deeds 1895 |

| 132.3 Institute Deeds 1950 |

| 132.4 Institute letters and bills |

| 134 - 138 Woodborough Hall - Index |

| 139 - 142 The Manor House Index |

| 143 - Nether Hall |

| 139 - Middle Manor from 1066 |

| 140 - The Wood Family |

| 141 - Manor Farm & Stables |

| 142 - Robert Howett & Mundens Hall |

| 200 - Buckland by Peter Saunders |

| 201 - Buckland - Introduction & Obituary |

| 202 - Buckland Title & Preface |

| 203 - Buckland Chapter List & Summaries of Content |

| 224 - 19th Century Woodborough |

| 225 - Community Study 1967 |

| 226 - Community Study 1974 |

| 227 - Community Study 1990 |

| 400 - 402 Drains & Dykes - Index |

| 403 - 412 Flooding - Index |

| 413 - 420 Woodlands - Index |

| 421 - 437 Enclosure 1795 - Index |

| 440 - 451 Land Misc - Index |

| 400 - Introduction |

| 401 - Woodborough Dykes at Enclosure 1795 |

| 402 - A Study of Land Drainage & Farming Practices |

| People A to H 600+ |

| People L to W 629 |

| 640 - Sundry deaths |

| 650 - Bish Family |

| 651 - Ward Family |

| 652 - Alveys of Woodborough |

| 653 - Alvey marriages |

| 654 - Alvey Burials |

| 800 - Footpaths Introduction |

| 801 - Lapwing Trail |

| 802 - WI Trail |