Woodborough’s Heritage

An ancient Sherwood Forest village, recorded in Domesday

If so, his high hopes have come to nought. No memorial of the family is there within the church; no effigies, no memorials, no tablets even only the Strelley arms in the gable beneath one of the very rare crucifixion crosses to be found in such a position.

In other ways Mansfield Parkyns was equally remarkable. He wandered like a mystic through Abyssinia and the desert, living a wild, nomadic life, getting back completely to the elementals, satisfying a wanderlust in a strange romantic manner. And when all his wanderings had lost their fascination he came in due course to Woodborough, content to settle in an English village, adorning the church towards which he had assumed an oversight.

Five hundred years lay between Strelley and Parkyns but their tastes were identical. Each felt that the church was worthy of the best he could offer. A queer, incomprehensible partnership, only proving once again that art is interminable, though life is regrettably brief.

The above article was first published in the Nottingham Journal July 20th, 1940

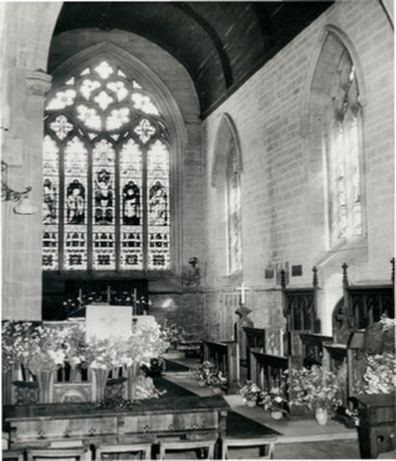

The splendid photograph above right of St Swithun's chancel taken in 1956 shows only some of Mansfield Parkyns work, namely the pulpit and the choir stalls, what cannot be seen are the four ceiling bosses in the chancel's arched roof and also the organ screen.

Woodborough may be very near to Nottingham as the crow flies, but it is far removed in other respects. Every furlong down the steep hill is welcome progress to rusticity. Suburbia and its lingering trail of ribbon building is completely left behind, with consequent peace of mind and a sense of tranquil detachment.

There was a time when the peace of Woodborough was sorely ruffled by the constant rattle of knitting frames. The village was submerged under the flood of commerce that followed on Lee's invention. Like Calverton and Lambley, Woodborough gave itself up completely to the demands for hose, whole families finding employment from one end of the village to the other in the rapidly developing mechanical production.

With the rise of the factory system and the establishment of vast machines, power-driven, attrition began to set in for the villages and gradually gave back something of long-lost peace and complacency. There may be some who would wish again the relative industrial importance of Woodborough, but the fact does remain that what the village has lost in commerce it has regained in peace.

By no means distinctive in beauty, Woodborough still has a charm all its own. No wonderful landmarks are there to set one's thoughts surging along the ages; no beautiful old houses, picturesque in architectural splendour or quaint with half-timbered appeal. No great barns or battered windmills; no little wrinkled bridges, not even a church of unquestioned purity of style. Only a chancel, and that, as though making up for all shortcomings elsewhere, a building of exceptional grandeur.

It must be acknowledged that carpenter, Richard Ward, assisted Parkyns in his work. What is not known however, which of the two men contributed the largest part. Sadly, Mansfield Parkyns died January 12th, 1894, very soon after they completed their work. [Ed 2009]

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Bosworth’s Woodborough "With an Artist at the Wheel"

A snapshot of Woodborough in 1940.

Down in the valley where the waters of the Beck gurgles pleasantly along, Woodborough spreads itself out like a great wrinkled monster. It has length but not breadth. It stretches along the highway with spasms of variegated building from a grand old church to a prosaic pumping plant, from stockinger's cottages to sparkling new villas, from thickly wooded drives to war-time allotments. Nothing arresting in its architecture, nothing remarkable in its situation.

Why it should have chosen such a site when the hill beyond presents such a wondrous view is rather a mystery, yet one which goes far back to days when more primitive man preferred the protection of the valley and its ready access to water. Woodborough loses such a lot by this inherited timidity. If only it could transplant itself to the top of the hill, how much grander the outlook might me. That panorama from the point where the Plains terminate is one of Nottingham's most magnificent prospects.

In these days of motor transport the hill loses much of its fearsomeness, but it must have been a cruel climb for carriers' carts when real horsepower was wont to set the pace. And yet, in spite of that, the people of Woodborough preferred the seclusion of the valley to the ever-changing prospect of rolling dumbles.

The chancel of St Swithun's is really the church. When Richard Strelley built it about 1350 his father also was erecting a church at Strelley [north west of the City of Nottingham] in which his magnificent effigy still reclines. The Strelley arms adorn the chancel at St Swithun's as though to secure for all time the recognition due to him who planned it. But while the chancel's relationship with Strelley is something for which it may be reasonably proud, its connection with other great architecture in the district gives it still greater cause for self-satisfaction.

'Twas a remarkable guild of builders upon whom Richard Strelley called when he first projected the sanctuary at Woodborough, a guild the like of which no other age can surpass. These men had built the famous chapter house at Southwell, the tower and spire of Newark, the magnificent church at Hawton, chancels at Car Colston and Epperstone, and most splendid of all, the Masonic masterpiece at Heckington, Lincolnshire. They grew old and honoured in their great endeavours and communicated to their sons and apprentices the true "mysteries" of their craft. They touched heights of craftsmanship superb and unexcelled.

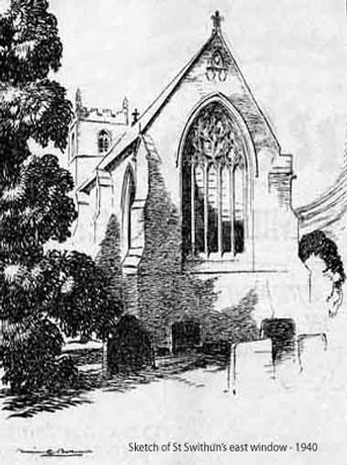

These were the men who came to Woodborough at the behest of Richard Strelley. Their work stands, possessing a masterly grace, finely balanced proportion, and a rock-like stability which has over-topped the centuries in spite of appalling neglect. When they had finished came the glass workers and those easy flowing reticulated spaces in the great east window blazed out in all the intoxicating splendour of medieval painted glass. The work of the masons remains, but little of the glass has survived. Think of the tragedy of it all!

Thoroton, the old antiquary whose tracks one is always traversing in the confines of the county, came to Woodborough in 1670, and the windows were then intact, so much so that he recorded in detail the brilliance and beauty of the work. But a century later, when Throsby came "the chancel windows......are so filthy, broken and patched that little can be made out to please by description". A generation later Stretton wandered round making his copious notes, and he records the sad finale, "now glazed with common glass and the painted lies in an old chest for anyone to carry away who chooses". The contemplation of such a loss is particularly distressing in a case like Woodborough, for the whole architecture of the chancel merits such rich adornment. Did Richard build the chancel as a chapel to enshrine his own memorial even as his father had done at Strelley?

| Navigate this site |

| 001 Timeline |

| 100 - 114 St Swithuns Church - Index |

| 115 - 121 Churchyard & Cemetery - Index |

| 122 - 128 Methodist Church - Index |

| 129 - 131 Baptist Chapel - Index |

| 132 - 132.4 Institute - Index |

| 129 - A History of the Chapel |

| 130 - Baptist Chapel School (Lilly's School) |

| 131 - Baptist Chapel internment |

| 132 - The Institute from 1826 |

| 132.1 Institute Minutes |

| 132.2 Iinstitute Deeds 1895 |

| 132.3 Institute Deeds 1950 |

| 132.4 Institute letters and bills |

| 134 - 138 Woodborough Hall - Index |

| 139 - 142 The Manor House Index |

| 143 - Nether Hall |

| 139 - Middle Manor from 1066 |

| 140 - The Wood Family |

| 141 - Manor Farm & Stables |

| 142 - Robert Howett & Mundens Hall |

| 200 - Buckland by Peter Saunders |

| 201 - Buckland - Introduction & Obituary |

| 202 - Buckland Title & Preface |

| 203 - Buckland Chapter List & Summaries of Content |

| 224 - 19th Century Woodborough |

| 225 - Community Study 1967 |

| 226 - Community Study 1974 |

| 227 - Community Study 1990 |

| 400 - 402 Drains & Dykes - Index |

| 403 - 412 Flooding - Index |

| 413 - 420 Woodlands - Index |

| 421 - 437 Enclosure 1795 - Index |

| 440 - 451 Land Misc - Index |

| 400 - Introduction |

| 401 - Woodborough Dykes at Enclosure 1795 |

| 402 - A Study of Land Drainage & Farming Practices |

| People A to H 600+ |

| People L to W 629 |

| 640 - Sundry deaths |

| 650 - Bish Family |

| 651 - Ward Family |

| 652 - Alveys of Woodborough |

| 653 - Alvey marriages |

| 654 - Alvey Burials |

| 800 - Footpaths Introduction |

| 801 - Lapwing Trail |

| 802 - WI Trail |