Woodborough’s Heritage

An ancient Sherwood Forest village, recorded in Domesday

Woodborough, an ancient Sherwood Forest Village

Introduction: There will be frequent references to Inquisitions and Inquisition Post Mortem. Historically Inquisitions were enquiries, conducted usually by local Lords of the Manor, acting as a Jury, to decide whether a course of action, usually by another local Lord of the Manor was fair, what would be its effects in regard to the Crown and to the local peasantry.

A definition of Inquisition Post Mortems by the Thoroton Society is as follows:-

“These records were concerned solely with the lands held of the King and were taken in order to determine what feudal rights accrued to the Crown on the death of any tenant in chief”.

The inquiry was held to determine:-

- Of what lands the deceased died possessed.

- Of whom and by what services the same were held.

- The date of death.

- The name and age of the lawful heir.

These Inquisitions and Inquisition Post Mortems are of great use to us in local history because they not only tell us who were the local gentry on a particular date, but also inform us about the way people lived, their problems and how the problems were dealt with, and they can all be found at the Nottingham Archive Office. Ancient spellings are used throughout this article.

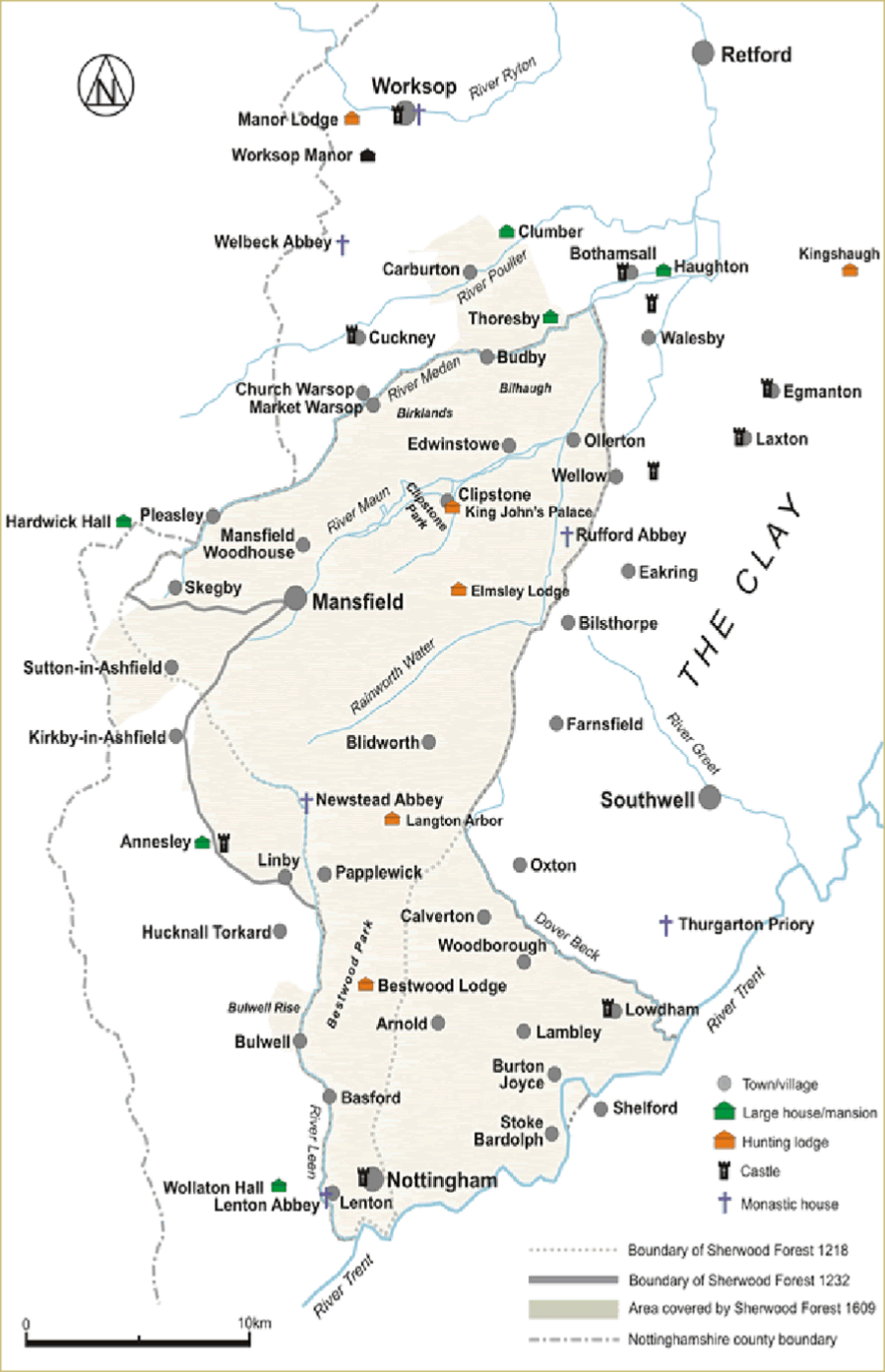

With acknowledgement to The Thoroton Society - Richard Bankes plan dated 1609 showing the extent Sherwood Forest

had on Nottinghamshire from the River Trent at Nottingham in the south and reaching up to Worksop in the north.

What does the word forest mean to you? An old but good definition of a forest was a portion of territory consisting of extensive waste lands including a certain amount of both woodland and pasture, circumscribed by defined metes and bounds within which the right of hunting was reserved exclusively for the King and which was subject to a special code of laws, administered by local as well as central ministers.

A Chase was like a forest but could be held by a subject. Offences in a Chase were usually punishable by Common Law and not by forest jurisdiction. However, Woodborough, which was in Thorneywood Chase, part of the wider Sherwood Forest, appears to have come under forest law, as the officers were concerned with petitions for coppicing, and for ensuring assarts were legal. [Assarts (Old Law). An assart was an illegal encroachment of the Forest for agricultural or any other purpose].

A document dated 1232 and Robert Morden’s map of 1695 show the extent of Sherwood Forest over that period. The boundaries were the River Idle in the north, the River Trent in the south, the Maun in the north east, the Dover Beck in the south east and the Rivers Leen and Meden in the west.

With all the water courses, plus the Rivers Poulter, Ryton and Rainworth Water, there would be an abundance of water mills – there are records of 12 mills on the Dover Beck [only three are shown above]. The mills tended to be on the Forest side of the boundary rivers and streams and all would most likely have had to contribute to the Royal coffers.

Sherwood Forest extended for approximately 20 miles north to south with an average width of 9 to 10 miles giving an area of roughly 175 to 200 square miles. You, (at least those with local knowledge), will appreciate how big Sherwood Forest is when you consider that an area, from Dorket Head to Timmermans (Sheepwash Bridge) and Spindle Lane to Ploughman Wood, only covers about 3 square miles.

Left: This is thought to be the 1767 Bowen map of Nottinghamshire.

Right: Cary's 1787 map in full, shows more accurately Sherwood Forest relative to Nottingham and Worksop.

Sherwood Forest and the 1609 Survey and Map by Richard Bankes: Sherwood was a royal forest dating from the twelfth century, surviving well into the eighteenth century as an important landscape feature and until the early nineteenth century as a legal entity. Occupying some 100,000 acres of central Nottinghamshire it was one of the most significant of the seventy royal forests in England in the Middle Ages.

The prime purpose of a royal forest was to provide an area where beasts of the chase (venison) could be fostered and hunted by the King and his followers. The crown's right to hunt included all freehold and tenanted land within a royal forest and officers were appointed to safeguard the king's interests and ensure that no agricultural activity contravened the forest laws protecting the vert (trees and ground cover).

From a book entitled - Nottingham Past Book of Essays in honour of Adrian Henstock, edited by John Beckett 2003. This chapter by Steph Mastoris - 'mapping Sherwood Forest'. Seven maps survive that were directly produced by Crown officials. By far the most important of these arose from the survey by Richard Bankes between 1608 and 1609. The map depicts the southern third of the forest extending from the River Trent in the south to the top of Bestwood Park, Arnold and Calverton parishes in the north. A written survey was also drawn up by Bankes providing sometimes fuller descriptions of the owners, occupiers, agricultural use, name and acreage of each parcel of land. As this written survey covers the whole of Sherwood Forest, it seems likely that Bankes originally produced maps of the area not shown on this extant map. Annotations on the written survey, together with references to this work in contemporary administrative records, revealed that Bankes' map was commissioned by Crown officials as preparation for a major campaign to detect and prosecute those landlords who had assarted land in Sherwood Forest. Within a few months of the completion of the map and written survey, a number of landowners were being summoned before royal commissions for defective titles to answer cases of assarting forest land without adequate permission to do so. The resulting litigation resulted in a considerable amount of new revenue for the Crown, as well as directly and indirectly motivating private landowners to commission map surveys of their estates.

The extent of woodland around Woodborough: Woodborough lies within the area known as Thorneywood Chase, at the southern end of the Royal Forest of Sherwood. The forest was divided into three parts or keepings, North, Middle and South. The South part including among others the villages of Lowdham, Lambley, Arnold, Bestwood Park, Bulwell, Basford, Calverton and Woodborough.

In 1231 Robert de Everingham of Laxton was the Chief Forester and his descendants continued to be Chief Foresters until 1289 when one of them abused the office of Chief Forester, incurred the King’s (Edward l’s) displeasure and the family were relieved of the office. However, during his term of office Robert would no doubt have journeyed through Woodborough on his patrols accompanied by a retinue of foresters, regarders, verderers and agisters.

As well as these minor patrols, perambulations or major surveys were carried out at intervals and those of Sherwood Forest record all the areas and boundaries visited. Records are available at the Nottinghamshire Archive Office for many of these perambulations including those of 1300, 1539, 1609, 1657 and 1793; in particular, the map of the 1609 with its survey by Richard Bankes provides considerable detail about Woodborough and its landowners. The perambulations marked the extent of the forest, its boundaries, water courses and any illegal encroachments or assarts.

In 1609 the main area of woodland around the village was to the west of the West Field reaching to the top of the valley and belonged to the Strelley family of the Upper Hall. At the time it consisted, as shown by the map above, of Woodborough Wood ² [Woodborrough Wood], Stoup Hill Coppice [Stoope Hill], Mardales [Mardakes], Fox Wood [Foxe Wood] and the Riddings [The Rydinges], the latter appears to have been a wood which had been clear felled, contained a lot of gorse and would have been classed as waste in forest terms. This large area of woodland and coppice covered about 530 acres. The other area was on the south side of the present Bank Hill and reached at least as far as ³ Aygrum Wells [Hagrams Well] on Lingwood Lane [this spelling of Aygrum probably dates from about 1300 AD.].

Notes:

¹ A full version of this map and its accompanying survey details of Landowners is published in The Thoroton Society

Record Series 1997, Sherwood Forest in 1609.

² Note that the above names in [ ] are the spellings consistent with the 1609 map.

³ For photograph and location map, see below.

It was owned by Mr John Wood of the Middle Hall (Manor). It included Sowe Wood also known as Sawwoode – probably forms of Southwood, and the present Stanley Wood then called Mr Wood’s Coppice. This woodland area covered about 56 acres. These two areas of woodland, totalling about 586 acres, appeared to have remained for about three centuries before and after 1609 until the time of the 1795 Inclosure Award. However, some names in the Woodborough valley area appear to have changed during the period to Old Coppice, Miers Coppice and Rough Riddings and all of the woodland appears to have been coppiced.

Left: Aygrum Well, as seen from Lingwood Lane looking due west towards Wood Barn Farm.

Right: Position of Aygrum Well relative to Woodborough Village, Sanderson 1835 map.

It is worth mentioning that another woodland known as Ploughman Wood [Hoeverley Woode], which is only one mile from Woodborough village and is in the Lowdham Parish, dominates Woodborough's southern skyline. It currently covers over 32 hectares and is one of Nottinghamshire's few remaining ancient woodlands, it is now in the care of The Nottinghamshire Wildlife Trust. Documentary evidence shows that it dates back to the 13th century and was part of an area of woodland covering more than 120 hectares.

Interestingly research has uncovered some of the earlier history of the South Wood going back well before the 1609 map. An Inquisition Post Mortem was held at the village of Cromwell on the death of Ralph Cromwell of Tattersall Castle on 4th November 1398 in the 22nd year of the reign of King Richard II. Among other things it states that Ralph Cromwell died owning a parcel of underwood called South Wood in the fields of Woodborough, held of the Archbishop York, by service unknown, worth nothing a year because it was within the King’s forest of Sherwood. His son and heir was also named Sir Ralph Cromwell.

Much later at another Inquisition Post Mortem held at Nottingham on 7th July 1498 in the thirteenth year of Henry VII after the death of Matilda Willoughby widow – it states a wood called South Wood in Woodborough by virtue of a gift made by Ralph Cromwell to Ralph Cromwell – Knight. Later Inquisition Post Mortems of the Willoughby and Meryng family are rather vague as to the ownership of South Wood and eventually it was owned by the Wood family, who may have held it as owners of the Lambley Manor before they came to Woodborough in 1607.

If any lord of the manor wished to assart or enclose a piece of the waste or forest, an Inquisition was held before a jury of his peers to see if the assart was detrimental to the King’s forest, his deer, or in fact any persons whatsoever – even peasants. Because the local lords had to fight on the King’s behalf and kept retainers, to ensure they did not get up to mischief the King made them do jury service over their peers so as to maintain order. When a lord or wealthy person died there was also the Inquisition Post Mortem, to see if anything from the deceased’s estate belonged to the King, or any fees were due to him. At an Inquisition held at Woodborough on 18th June 1293 the King, Edward I, wanted to know whether it would be to the King’s damage if he should grant to Sir Hugh Bardolph, who in the King’s service had been ordered to depart into the parts of Gascony, in order to cover his costs, might cut down and sell timber in his wood at Gedling to the sum of £100 (Edward was contesting his rights as a vassal in Gascony with Philip IV of France).

On the face of it, it seems reasonable that if Hugh of Bardolph was commanded by the king to go and do foreign service for him he should be able to finance the expedition and sell £100 worth of his timber. However the jury – who were all local men thought differently. They included Sir Robert de Jorz (Burton Joyce), Peter of Lowdham, Thomas of Bulcote and Roger of Gedling, and as it concerned the king’s forest, four verderers, seven regarders and two agisters were also present. Their conclusion was that if the King gave Sir Hugh permission to cut £100 of timber from Gedling Wood, there would virtually be no timber left standing. Also because the wood was near to the King’s deer enclosure of Bestwood haie, Gedling Wood was a good place for harbouring the King’s deer. (A haie was an enclosure within a park or forest, fenced with a rail or hedge or sometimes both, where the deer could be fed by the foresters and possibly released for hunting). The jury also said that the people who lived in Gedling would have no place to feed up their pigs on the acorns and it would be detrimental to those people who had other common rights in the wood e.g. timber for repairing their houses, barns, plough carts, handles for tools and dead wood for kindling. So you see the welfare of the peasants had to be considered too as they did boon work for the lords of the manor and the lords would not wish it to be done grudgingly. It would be interesting to know if Hugh of Bardolph did eventually go to Gascony and if so how he raised the money for the expedition.

Inquisition re mill on Thorndale Plantation - Inquisition at Calverton 1347: Alexander of Gonalston wanted to build a mill and divert the Dover Beck at Thorndale – which is the plantation between Beanford Lane at Oxton where the ford is and the main Nottingham/Oxton road and if it would affect the King’s forest. The Inquirers, one of whom was John de Blidworth of Woodborough who was a Forester, decided that there would be no profit for the King, presumably the mill would have been on the east side of the stream and not in the King’s Forest so Alexander would be able to divert the stream and build the mill. Lowdham miller was also one of the inquiry team?

Officers of the Forest - Chief Forester, Verderers, Regarders, Agisters and Forest Courts

Chief Forester: The Chief Forester, Warden or Keeper was allowed, in his official capacity, to distribute a certain amount of venison to the county gentlemen of the district without obtaining a direct warrant. Perhaps this was to compensate to some extent for the damage done by the king’s deer wandering on to their home farms or to dissuade them from taking any deer illegally.

Red deer typical of the 1600 period and a typical open space In Sherwood Forest for deer cover.

The Chief Forester would also be responsible for carrying out the King’s wishes as to the distribution of timber. Around 1228 there were Royal Grants of oaks from the forest to various religious communities for building purposes. As there were a number of priories and abbeys in Nottinghamshire at that time probably many of them benefited.

Verderers: Verderers dealt with all legal matters concerning the forest. They were officers who had charge of the vert and venison. In forest law vert was considered to be every green leaf or plant having green leaves that could give food or cover for the deer.

They had to deal with such offences as trespassing, taking or attempting to take the deer, and taking or cutting down timber without permission. The verderers were elected by the freeholders and were unpaid and without privileges. In this area it would seem they were usually county squires, in 1331 Lord John of Annesley and Samson de Strelley were verderers.

Another of their duties was to take special care of the deer during the time the hinds dropped their fawns. This usually happened from about a fortnight before to a fortnight after Midsummer’s Day and during this time the forest was closed to prevent disturbance. During the winter the verderers supplied the deer with deer-browse or tree clippings when necessary.

Regarders: Regarders were knights who reported on the condition of the forest in detail. Their main responsibility was to ensure that no person enclosed or ploughed up any part of the forest or waste without permission. They reported any encroachment, whether for building a house, barn, mill, or for any other purpose. Robert of Winkburn was a regarder in the reign of Edward lll (1350-ish). Regarders had to be present when trees in the forest were marked for felling.

Agisters: Although certain people, in particular those who were freeholders in the forest or on land adjoining it, had certain rights of pannage (the right of pasture for pigs either in woodlands or on common pasture) and pasturage in the forest, they had to pay for the privilege. The officers who organized and supervised the feeding of pigs and cattle in the forest were called Agisters. They were responsible for collecting the money, ensuring that only the number of pigs registered were in the forest, the charge being one penny (1d) for each pig over one year old, and that the pigs were only in the forest for the specified period, usually from about 11th September to 11th November. Anyone having more pigs in the forest than had been registered could have some of them confiscated.

Plough oxen, horses and sheep were only allowed restricted access to the forest as they did more damage and goats were forbidden. The horses probably had to be hobbled as in one Woodborough inventory horse-locks were mentioned. The pigs benefited from the surfeit of acorns and beech mast fattening them up, but the forest itself also benefited as some acorns and beech mast were often buried by the pigs when feeding, so helping to rejuvenate it.

The Forest Courts: There were three different forest courts – the lowest was the Attachment Court – also known as the 40 day Court or Woodmote. The middle one was the Swainmote and the highest the Justice in Eyre’s seat.

Any person breaking the Forest Law such as trespassing, gathering wood, acorns, beech mast or committing any minor offence could be fined unless the damage was estimated to be more than four pennies (4d). If more he would be attached by the forester and would have to find two people willing to stand bail for him to appear at the next Attachment Court before the Verderers of the Forest.

If a trespasser was found to have killed a deer, or be carrying one away, he would immediately be arrested and imprisoned until the King or a Justice in Eyre bailed him to appear at the next Eyre.

The Eyre was supposed to be held every seven years but circumstances often meant that this was not the case. When Eyres were held they were rather impressive affairs. The local Sheriff had to order the following to attend. All the gentry and other freeholders who had holdings within the bounds of the forest, the reeve and four men from each township or village, all the foresters and verderers including those who had previously been in office when any of the offences before the court were committed, together with all the regarders and agisters.

To some poor peasant who had been unlucky enough to have been caught red-handed with a deer and who had perhaps been waiting several years to be tried, being brought before such an assembly must have been a terrifying experience.

On the 13th June 1325, Edward ll reign, a Woodborough man, Hugh of Wotehall and three other men went to the wood at Arnold on a hunting expedition armed with bows and arrows. They must all have known the likely penalties for being caught armed in the King’s Forest, but either a thirst for adventure or from sheer necessity as hungry peasants, they considered the risk worthwhile. Difficult as it would have been for four men on foot to creep through undergrowth to within arrow distance of a deer, they managed to loose an arrow which severely wounded a deer but allowed it to escape. For one reason or another, the four men decided it would not be prudent to follow the injured beast. When the deer’s carcase was eventually discovered by foresters, the arrow was still embedded in it, but the deer’s flesh had rotted and been partly eaten by vermin. The men involved in this killing were somehow identified and those apprehended were brought before the Attachment Court and presumably had to find pledges for bail until brought before the Eyre, which is the highest court.

Although as mentioned previously the Eyre was supposed to sit every seven years, it was almost nine years before Hugh from Woodborough was presented in March 1334 (Edward lll) and sent to prison. In the meantime, one of the other men had died and two did not appear before the court. They had probably fled the county and as they seemed to have no property which could be destrained, the court outlawed them. At a later date Hugh was brought out of prison and pardoned because he was poor. Perhaps the authorities realised that there was no way they could be reimbursed for feeding him and releasing him solved the problem.

The Swainmote met at least three times a year in accordance with the Forest Charter of 1217 to manage the Crown’s woodlands. A fortnight before Michaelmas (29th September), it would regulate the pasturing when, the freeholders would say, how many pigs they intended to feed in the forest. It also met on St Martin’s Day (11th November) when the pannage dues were collected. The Swainmote also met when the forest was closed and cleared of sheep and cattle, just prior to Midsummer’s Day before the hinds had their fawns. The Court is also considered to have been busy during the pannage period to fine those who had pigs in the forest that they hadn’t registered with the Agisters.

Coppicing – the Law of the Forest: When a wood was coppiced and the underwood cleared it was necessary to ensure that a number of good young saplings of oak and ash were left to develop into mature trees for the construction of buildings and ships. It has been estimated that about 2000 mature oaks were needed to build a Man of War.

Strict laws were enforced [see agreement below] concerning coppicing in the King’s forest. Firstly the owner of the particular piece of woodland would have to petition the Justice in Eyre or Warden of that particular forest to encoppice a given acreage or area. Two verderers would be sent to view the parcel of woodland and give their view as to whether the felling and coppicing were justified. If approved by them, they would send a certificate to the Justice in Eyre who would issue the owner with a grant or permit to cut down, sell or use the timber for his own purposes. The grant would only be given if certain conditions were fulfilled and a bond or other security had to be lodged with the Forest Court.

The coppiced area had to be securely fenced to prevent the entry of cattle for the first 3 years after coppicing. Only a limited number of cattle, as specified by the Forest Laws were allowed to graze in it for the following six years. This was to allow the new growth of wood to develop. If the area to be coppiced was surrounded by additional woodland the application was looked upon more favourably as the King’s deer would have alternative cover and shelter until the coppiced area recovered.

TO ALL WHOM THESE PRESENTS SHALL COME THE RIGHT

HONOURABLE THE EARLE OF CARDIGAN CHIEF JUSTICE IN

EYRE OF ALL HIS MAJESTYS FORRESTS CHASES & PARKES

TRENT NORTH SENDETH GREETINGS

Forasmuch as I was lately petitioned by William Edge and Jane his wife of Woodborough within the chase of Thorney Woods in the forrest of Shirwood in the County of Nottingham Owners of a piece of Woodland Ground called Agrim Wells Coppice situate and lying within the Lordship of Woodborough aforesaid containing by Estimation Eight Acres of forrest measure that they may have liberty to cutt down and Incoppice, the same and being certified by Richard Porter and William Molyneux esquires two of the verderors of the said Forrest by their certificate dated the Twenty Fifth Day of February last that the said petitioners Request may be granted in their giving security to preserve the same when cutt down according to the Laws and Customs of the said Chase and forrest for nine years from the time of cutting the same. Know yee therefore that I the said Earle as much as in me lyeth Do give and Grant to the said William & Jane Edge and their assignes full power to fell cutt down and take and carry away the wood growing in the said woodland ground hereby petitioned for (Except Hollys and Crab Trees) provided they keep out of the said Woodland Ground so to be out down all Cattle whatsoever (The Deer Excepted) for the three first Intire Years after the said Coppice is Cutt and provided for Six Years next after they only stock the same with such Cattle in Quality and Number as are allowed by the Laws of the said Chase and Forrest to depasture therein and provided he do and shall well fence and Sufficiently keep Coppiced and Inclosed the said Woodland Grounds for the several terms of three and six years in all nine years¬ next after the Cutting Coppicing and Springing thereof according to the Assize of the said Chase and Forrest and provided he give a Bond to me or my Deputy Steward of the said Forrest of a reasonable penalty for the performance of the provisos and Conditions herein before mentioned.

Given under my hand and Seals this Tenth Day of May in the year of our Lord 1746

Cardigan (seal)

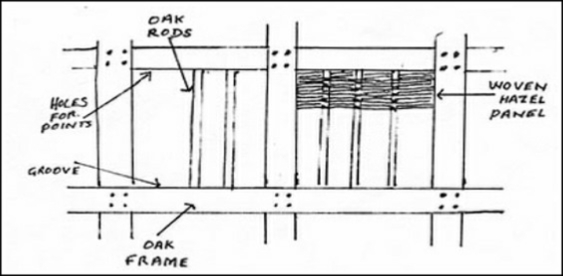

Typical wattle fencing.

Coppicing in practice: The practice of coppicing was the felling of certain types of mature trees to a little above ground level. The stumps or stools remaining sent up several stronger shoots which were ideal for posts and rails for fencing purposes. The woodland trees used for coppicing in Woodborough were probably mostly oak, ash and hazel on dry ground and alder in the lower, wetter areas where willows would also have been pollarded that is, cut off at about head height.

Left: Typical ash coppicing.

Right: Typical hazel coppicing.

Below:The Doverbeck running under Shelt Hill is the south-eastern boundary of Sherwood Forest.

The coppiced oak needed a period of about 20 years to produce useful timber, the bark being used for tanning leather and the wood for the timber frames of houses, barns, furniture and for fence posts. The hazel only needed about 7 years to mature and would have been used for hurdles and fold fleaks for enclosing the sheep during the winter months, either in the farmyard or on the open fields to provide manure. Hazel would also have provided the lattice-work for the wattle and daub infill in the village’s timber framed houses, before the use of brick infill, and for thatching spars and baskets.

The oak rods are pointed at the top and cut to a wedge shape at the bottom. Holes are drilled in the top of the panel frame and a groove cut into the bottom of the frame allowing the points of the rods to fit into the holes and the wedge to slide into the groove. Round the rods a panel of hazel is woven and then covered with daub, a mixture of chopped straw, animal dung and clay which is then lime washed to make it waterproof.

Diagram showing the use of oak rods in buildings.

Ash wood is hard and elastic, it is especially suitable for axe shafts and tool handles, for carts, agricultural implements and furniture. The oak and ash were also used for fences and rails round the homesteads and were listed on the inventories as they belonged to the tenant.

Petition to encoppice: A petition by Philip Lacock of the Upper Hall (Woodborough Hall) to enclose 12 acres of forest measure of Stoop (sic) Hill Coppice on 11th February 1660 was granted on the 25th by William, Earl of Newcastle and Lord Warden of the Forest of Sherwood after the site had been inspected by two verderers. As it was surrounded by other woodland there was plenty of cover for the Royal game, but the enclosing of the coppice had to be according to Forest Law and Lacock had to give good security for this to the Forest Court. ‘Stendells’ and ‘weaners’ which were young saplings had to be left to develop into mature trees. And what happened to the timber? Probably used for the rebuilding of the Upper Hall before he died in 1668.

A petition dated 13th December 1708 by Philip Lacock, second son of the previous petitioner, to the Duke of Devonshire who was the Justice in Eyre of all the royal forests, chases and parks north of the River Trent, asked for leave to cut down the wood and underwood, and coppice a parcel of wood or woodland ground, again on Stoop (sic) Hill Coppice. The verderers appointed Monday 17th January 1709 to view the site of the proposed felling and the certificate was granted on that date with the usual conditions. A proviso of most of these coppicing petitions was that no holly or crab-apple trees were to be cut.

The verderers mentioned that the conditions regarding the grazing of cattle in the new coppices were not always adhered to and much damage to the new growth had been caused because of the inadequate fencing or over-stocking – a warning to Philip perhaps! And what happened to the timber from this petition? This Philip Lacock built or re-built the Home Farm, now called the Hall Farm, which according to the plaque over the (front) doorway was completed in 1710, two years after the petition. Had Philip planned to build Home Farm and needed a good supply of timber for the beams, joists, rafters, purlins etc? If so, his petition to encoppice part of the Stoop Hill woodland would have enabled him to prepare the oak he needed for building the house and to coppice the oak and hazel at the same time. He would have needed quite a lot of posts and rails to enclose 12 acres of coppice.

Hall (or Home) Farm house in 1922, a stone on the wall

above the porch has the inscription '1710 Philip Lacock'.

Home Farm appears to have been built on waterstone foundations, possibly of a previous timber framed building and the use of brick in the 1710 building followed the trend of the time for the gentry to build in brick. Possibly a little of the timber framing of the former house has been incorporated in the present building but undoubtedly much new timber was needed and Stoup Hill woodland may well have been the source.

You may have noticed that both petitions to coppice were during the winter months. It would have been easier to work on frozen ground and when the sap was not rising. Also transporting the timber, either by sledge or horses dragging it downhill to the Hall sawpit would have been much easier in the days when they had proper winters.

Mountague Wood died aged 80 in 1741 and only he and his sister Katherine were alive when he/they founded Woods Foundation School in 1736 and she died in 1738 aged 86. It would be interesting to know what the condition of the Middle Manor was when Mountague died, after it had been occupied by elderly residents.

In 1746 Jane Edge, with her husband William, had inherited the Middle Manor five years previously and had petitioned to encoppice a piece of woodland known as Aygrum Wells Coppice, a piece about 8 acres in extent. The petition was received by the Earl of Cardigan, Lord Chief Justice in Eyre of all the King’s Forests, Parks and Chases north of the Trent at that time. Aygrum Well is the name given at present to the spring on Lingwood Lane near Woodbarn Farm at the bottom of the steep hill leading to Lambley. As the present parish boundary and that of the 1609 map run close to the spot, the coppice may have been on the west side or on both sides of the present Lingwood Lane as the road to Lambley was not made until after enclosure.

Although the name of the wood confirms that it had previously been coppiced, it was not fenced off at the time of the petition, probably because most of the trees in it were mature and would not be damaged by browsing cattle. Two verderers, Richard Porter and William Molyneux, Esquires, certified that the petition was acceptable so long as the laws and customs of the forest were adhered to. The Earl of Cardigan therefore granted Jane and William Edge the right to fell, cut down and carry away the timber apart from the usual holly and crab-apple.

Now to slightly more recent events. At a Nottingham court on 14th July 1783, William Sherbrooke returned the conviction of John Mellows of Woodborough for having in his house part of a Fallow Deer suspected to have been unlawfully killed. Mellows was adjudged to have forfeited the sum of £30. At a Nottingham court on 10th January 1785 George Stocks, late of Woodborough, cordwainer, was fined £20 for unlawfully coursing, hunting and driving deer on 25th December last in Thorneywood Chase in the parish of Lambley, several Fallow Deer, with intent to take or kill some of them.

According to an inquiry into the state of Sherwood Forest in 1789, immediately before Enclosure, there were no deer, apart from about 500 Fallow Deer in Thorneywood Chase held by the Earls of Chesterfield as keepers/rangers of the Chase by a grant of Elizabeth I in 1600. This is confirmed by Lowe, the Nottinghamshire agriculturist, who wrote in 1798 that after the Inclosures of Carlton, Gedling, Burton Joyce and Bulcote, Lowdham, Lambley and Woodborough there were no deer left in Thorneywood Chase.

The Earl of Chesterfield was apportioned some land in the Woodborough Inclosure Award because of the reduction of Thorneywood Chase by the Inclosure and for all the Woodborough Forest land he lost, he was given a measly 15 acres, 3 roods and 35 perches, and of what is left of the forest today only isolated small bits of woodland such as Fox Wood and Stanley Wood remain.

.jpg)

Above: Detail of the 1787 Cary map showing the position of Woodborough as just below the ‘gh’.

.jpg)

.jpg) Next page

Back to top

Next page

Back to top

Above left: Fox Wood in the distance, viewed from Bank Hill Farm.

Above right: Stanley Wood which is both above and behind Bank Hill Farm.

Acknowledgements:

- Text researched and prepared by Peter Saunders.

- Some maps and text from the Thoroton Society Nottinghamshire.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

| Navigate this site |

| 001 Timeline |

| 100 - 114 St Swithuns Church - Index |

| 115 - 121 Churchyard & Cemetery - Index |

| 122 - 128 Methodist Church - Index |

| 129 - 131 Baptist Chapel - Index |

| 132 - 132.4 Institute - Index |

| 129 - A History of the Chapel |

| 130 - Baptist Chapel School (Lilly's School) |

| 131 - Baptist Chapel internment |

| 132 - The Institute from 1826 |

| 132.1 Institute Minutes |

| 132.2 Iinstitute Deeds 1895 |

| 132.3 Institute Deeds 1950 |

| 132.4 Institute letters and bills |

| 134 - 138 Woodborough Hall - Index |

| 139 - 142 The Manor House Index |

| 143 - Nether Hall |

| 139 - Middle Manor from 1066 |

| 140 - The Wood Family |

| 141 - Manor Farm & Stables |

| 142 - Robert Howett & Mundens Hall |

| 200 - Buckland by Peter Saunders |

| 201 - Buckland - Introduction & Obituary |

| 202 - Buckland Title & Preface |

| 203 - Buckland Chapter List & Summaries of Content |

| 224 - 19th Century Woodborough |

| 225 - Community Study 1967 |

| 226 - Community Study 1974 |

| 227 - Community Study 1990 |

| 400 - 402 Drains & Dykes - Index |

| 403 - 412 Flooding - Index |

| 413 - 420 Woodlands - Index |

| 421 - 437 Enclosure 1795 - Index |

| 440 - 451 Land Misc - Index |

| 400 - Introduction |

| 401 - Woodborough Dykes at Enclosure 1795 |

| 402 - A Study of Land Drainage & Farming Practices |

| People A to H 600+ |

| People L to W 629 |

| 640 - Sundry deaths |

| 650 - Bish Family |

| 651 - Ward Family |

| 652 - Alveys of Woodborough |

| 653 - Alvey marriages |

| 654 - Alvey Burials |

| 800 - Footpaths Introduction |

| 801 - Lapwing Trail |

| 802 - WI Trail |