Woodborough’s Heritage

An ancient Sherwood Forest village, recorded in Domesday

Update report – Spring 2010

The WI recorded headstone inscriptions and the churchyard flora and fauna. They noted 155 visible headstones in the churchyard, of these about 50% are weather damaged, some to an extent that nothing can be discerned. Recently obtained records show that over 2462 burials took place between 1572 and 1879. The churchyard closed for burials in 1878 when it was deemed to be full, a new cemetery opened on Roe Hill in 1879.

All headstones in the churchyard have been photographed; this in itself has enabled some names and dates to be read more easily and thus it has been possible to complete some of those incomplete inscriptions. Additionally baptisms, marriages and burial records for Woodborough have been acquired; these have been transcribed by the Nottinghamshire Family History Society from records held at the Nottinghamshire Archives Office. Having these data discs has enabled cross checking to take place resulting in more information to be included about the deceased’s name, date of death, date of burial and age at death.

With reference to earlier reports about visible headstones; it is possible that there are headstones lying beneath grassed areas. With the help of St Swithun’s and Nottinghamshire County Council archaeology department it is soon hoped to carefully and respectfully check the open areas for hidden headstones. If more are found this will compliment the excellent work carried out 28 years ago by the Woodborough WI.

In May 2010 (see below) an outline of a forthcoming geophysical survey being undertaken by the Nottinghamshire County Council archaeology department was produced. The survey was to last one week.

One objective was to establish if there were fallen headstones lying just below the surface of the open grassed areas of the churchyard. It had been hoped to find some, but alas none were found. That leaves 154 plus 4 that the WI did not record, visible headstones now known and on view. It was reported that at least 50% of these headstones have become weather damaged over the years and can only be read with difficulty, or in some cases not at all. Members of the Photographic Group have been studying the damaged headstones with a degree of success, they have been able to completely identify or partly identify some of those not previously recorded by the WI.

In the week they were at St Swithun’s, the Nottinghamshire archaeology team undertook a geophysical survey. They accurately recorded the boundaries and features of the churchyard. They also plotted the exact position of the church, all headstones, trees and shrubs currently on the site. They also recorded the ‘graffiti’, including several ‘mass dials’ which can be viewed on the outside south wall of the church. They noted mason’s marks inside the church and plotted the position of engraved flagstones marking burials within the church.

There are still some headstones that need further examination to determine their inscriptions; this will proceed during the summer months. The archaeology team will shortly produce an accurate plan of the churchyard and a detailed report of their findings. We hope this report will be available in church for residents and visitors to read.

Nottinghamshire County Council archaeology department will re-visit Woodborough to record the condition and type of materials used for the headstones; they also plan to record inscriptions where previous attempts have proved unsuccessful.

----------------------

1. Introduction to Final Report Autumn 2010: Parish records began in 1572 between then and 1879 there were at least 2462 burials when the churchyard closed. But with only 158 (154 + 4)visible headstones it was thought there could be many fallen headstones buried under grass or shrubs.

Members of the Woodborough Photographic Recording Group (WPRG) commenced a social history survey of the headstones in the St Swithun’s churchyard during June 2009. The aim was to expand on the survey undertaken by the Woodborough WI in 1982.

The work consisted of a photographic record of the headstones, along with a record of the details from the headstones. This was compared with the WI list, and resulted in an updated record. The new record was cross-referenced with the parish records. The exercise resulted in 90% of headstones being identified, an increase from approximately 50% achieved by the WI.

As part of a Nottinghamshire County Council Local Improvement Scheme, and in conjunction with the WPRG, a graveyard condition survey of St Swithun’s Churchyard was carried out by Nottinghamshire County Council Community Archaeology. The survey was undertaken in three parts; firstly a map of the locations of gravestones on the surface was created, secondly a sub-surface probing survey searched for stones that had been lost or buried, thirdly a full gravestone recording condition survey of the stones and memorials in the churchyard, and within the church was undertaken.

The survey took place to the specifications for graveyard recording prescribed by the Council for British Archaeology and English Heritage (Mytum 2002).

Left: Michael Harrison & Margaret Kirk recording memorial inscriptions in 2009.

Right: David Bagley, Margaret Kirk & John Hoyland probing for hidden memorials in 2010. All are WPRG members.

2. Site Location Geology and Topography: The churchyard of St Swithun’s. Woodborough is at OSGR 463170, 347710 (see Figures 1 and 2 below). The area is underlain by bedrock of the Triassic Mercia Mudstones Group. The rocks of this group present at this location are mudstones and siltstones of the Radcliffe formation, siltstones and sandstones of the Sneinton formation (known locally as skerry), and sands of the Sneinton formation. These bedrock formations are overlain by superficial quaternary deposits occupying the lower sections of valleys. These consist of clay, silt, sand and gravel deposits, including Head (erosional) deposits, and alluvium (waterborne) deposits of Holocene age.

.jpg)

Above - Figure 1: Woodborough village shown in relation to Nottingham. Figure 2: Survey Area within the churchyard.

Woodborough is situated in a valley, a tributary of the Doverbeck. The village is surrounded by high ground to the north, south and western sides. St Swithun’s church is recorded on the Nottinghamshire Historic Environment Record as Monument M1892. The graveyard is well maintained with mown grass and tended vegetation.

3. Historical and archaeological background: St Swithun’s church dates at least from the Norman period, with the north re-set doorway (blocked) being ‘Norman, of three orders, with colonnettes with scalloped capitals and cable zigzag mouldings of the voussoirs’ (Pevsner 1979). The chancel dates from the mid-14th century, but much of the church was restored in the period 1891-97 and the mid-20th century. The majority of window glazing dates from the period 1907-1910. The tower has a 13th century base and a perpendicular top (HER). The church is notable for graffiti especially on the external south wall, with a number of mass dials being preserved.

Previous archaeological work within the churchyard includes the excavation of foundation and service trenches for the construction of a new extension to the south aisle of the church by JSAC in 1999. An inhumation was encountered lying immediately below southwest drainage pipe. This extended outside the evaluation trench and was left in situ. Also during the excavation work significant numbers of disarticulated human remains were recovered. A dump of bones was found below the existing tarmac footpath at the southeast corner of the new foundation trench. The dump consisted of fragments of at least four and up to seven human skulls along with a number of larger bones. The lack of smaller bones pointed to this feature being a re-internment. All bones were re-buried (JSAC 1999).

A watching brief conducted in 2000 found no archaeological remains (Brooke 2000). The Nottinghamshire HER also locates a mound in the northeast corner of the churchyard as element number L10293.

4. Aims and Objectives:

- To record the locations of all gravestones in the churchyard, and to produce a 2-dimensional map showing their positions.

- To discover if there are buried gravestones in the churchyard and to map their locations. The number of extant gravestones at 158 is far less than the 2462 burials listed in the parish records from 1572 to 1879 when the records were kept.

- To produce a 3-dimensional model of the site using data recorded during the survey.

- To record details from the stones including full transcripts of surviving texts, measurements of dimensions, photographic and fully illustrated record.

Right - Figure 3: Geology of Woodborough.

5. Methodology

5.1 Mapping of surface features: The survey was carried using a Leica Flexline TSO6 Electronic Distance Measuring (EDM) Total Station. Points were recorded for each gravestone. Control of survey was maintained using initial coordinates and height taken from Ordnance Survey data, further control points were then pegged out around the site. These points provided lines of sight for optical survey, acting as station location points. Data was prepared and final maps created using MapInfo Geographical Information Systems (GIS) software.

5.2 Mapping of Subsurface features: The total station mentioned above was used to peg out a 25m base line in the south eastern area of the churchyard. From this base line a grid of 5m squares was pegged around the churchyard. This grid was then used as a guide for probing the ground at 0.5m intervals in both x and y axis. The probe survey was undertaken using 1 meter long metal rods, 1 centimetre m in diameter. The rods were entered into the ground to a depth of 10-20cm. Where a subsurface feature was encountered more intensive probing established its extent. Shallow features 10-20cm below the surface were uncovered and recorded.

5.3 Gravestone survey: The third phase of the project was to conduct a survey of the monuments in the graveyard, recording the details, construction materials, decoration, size, and condition. An example record sheet can be seen in Appendix 1. The survey work was carried out by the WPRG Group alongside volunteers from the community archaeology database. Nottinghamshire Community archaeologists supervised the survey to ensure that standards and guidance for recording were adhered to. A photographic record consisting of five photographs per memorial was taken. Each record included an overview photograph to show the grave’s location and photographs with and without a photographic board.

6.0 Results

6.1 Mapping and subsurface survey results: The mapping survey recorded 158 standing gravestones within St Swithun’s churchyard. The survey also recorded the names and locations of 103 square stone cremation memorials, and the location of two buried stones discovered by the probing survey. The mapped gravestones were given a number and details taken to allow comparison with previous work, and to facilitate use of the map in the gravestone recording survey. The map containing these details is available as part of the archive, and working copies were given to WPRG (see Figure 4 for the locations of the features mentioned above). The plan below is now sited in the NAVE on the NORTH wall (opposite the main entrance doorway).

Above - Figure 4: St Swithun’s Churchyard map showing surface gravestones, subsurface features.

This plan is clickable and will open a larger image.

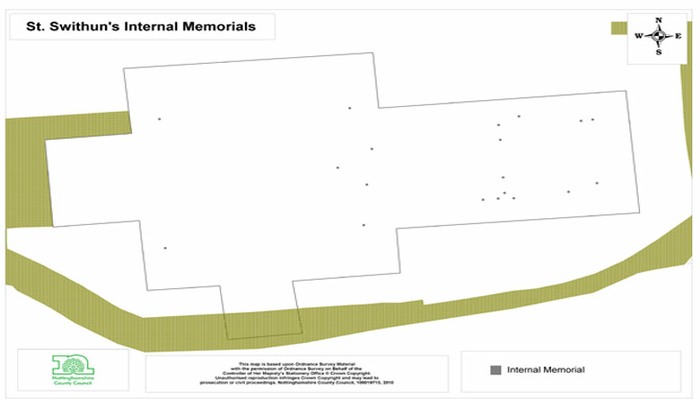

The subsurface probing survey discovered only two features present in the churchyard, which are marked on Figure 4. These were photographed and appear below in photographs 1 and 2. The survey also mapped 18 memorials within the church as shown in Figure 5 below.

Above - Figure 5: Showing position of internal memorials

Photograph 1 shows feature 001. The feature consists of the base of a gravestone broken at ground level. The stone is 57cm in width and approximately 5cm thick. To the east side of the stone are five clay bricks used as packing stones to prevent the stone collapsing due to subsidence above the burial.

Above - Pictures 1 & 2: Showing buried features facing west.

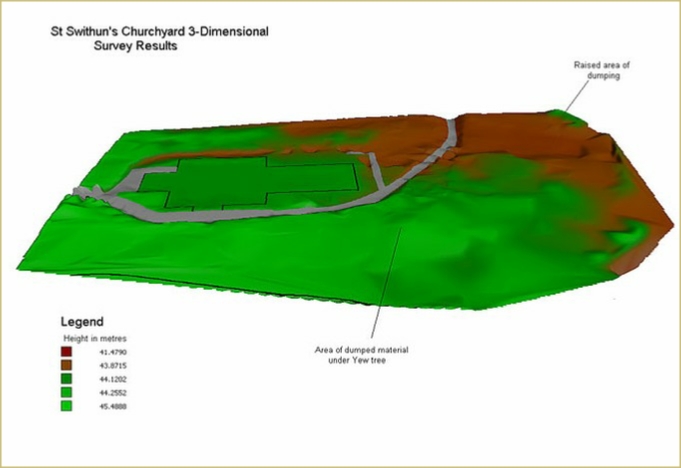

Photograph 2 shows what appears to be the top right corner fragment of a gravestone. The remaining fragment is 35cm left to right by 40cm bottom to top as seen in the photograph. Carved bordering can be seen to the top and right hand sides of the stone. The stone is broken to the left and bottom sides as seen in the photograph. The illegible remains of carving can be seen towards the top left of the stone. The stone is of a similar kind to that in photograph 1, but no definite association is possible from the remains. As part of the survey height or ‘Z’ coordinates were recorded alongside x and y locations. This enabled a 3-dimensional digital terrain model (DTM) of the churchyard to be created in Vertical Mapper software, an extension of MapInfo GIS software. The results are shown in the image in Fig. 6.

Above - Figure 6: A 3-dimensional model of St Swithun’s Churchyard.

6.2 Gravestone condition survey results

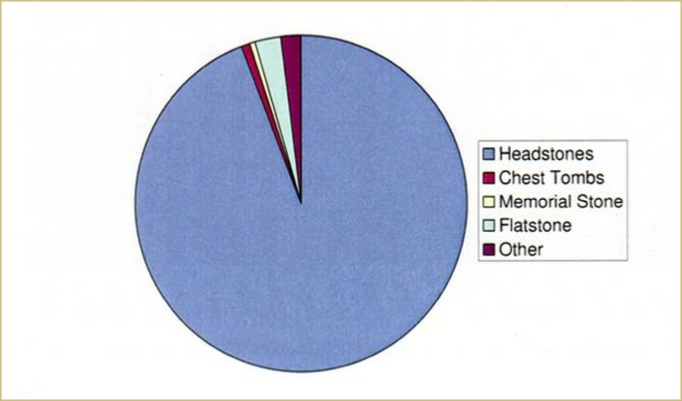

6.2.1 Monuments in the Graveyard: A total of 158 monuments were recorded in the graveyard over the course of 3 days. As Figure 7 below shows the vast majority (149) of the monuments are headstones. The other monument types include a chest tomb, flat stones and low kerbstone surrounded flat monuments.

Above - Figure 7: Pie chart showing the type of monuments in the graveyard.

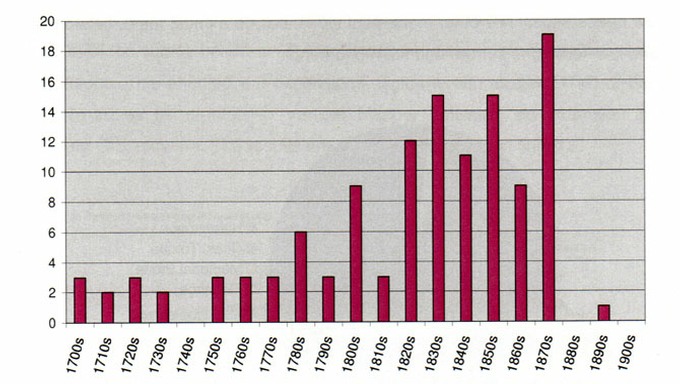

The earliest readable date visible in the graveyard is 1708 (monument no, 135), and the most recent readable date is 2004 (no. 054), although this late one is a memorial stone rather than a grave marker. As the chart below shows there is a steep drop-off in monuments from the 1870’s to the 1880’s, and this presumably coincides with the closure of this graveyard and the referral of subsequent burials to a nearby cemetery. A reference to this is seen on monument 048 which reads; ‘In Loving Memory of Ann, Wife of John Mellows, who died June 30th 1873 aged 69 Years. Also of John Mellows who died December 2nd 1884 aged 82 Years, Interred in the Cemetery Grave number 20’. This is clear evidence that St Swithun’s graveyard was closed to burials prior to 1884.

With the inclusion of number 054, which is a memorial stone rather than a grave marker, there is only one burial after the 1890’s, and this is memorial number 140. This marks the grave of Mansfield Parkyns, the mid-19th century of Woodborough Hall who carved the Victorian stalls inside the church (Pevsner, 384).

Above - Figure 8: Bar chart showing the number of memorials from each decade period.

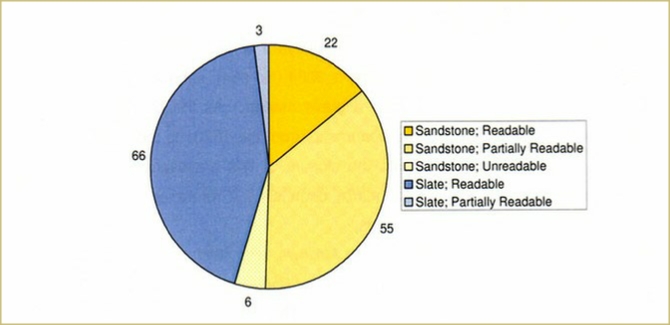

Above - Figure 9: Pie chart showing the relative legibility of

sandstone monuments against the slate monuments in the graveyard.

All but six of the monuments within the graveyard are made of slate or sandstone. There are slightly more sandstone memorials (83) than slate ones (69), but as is very clear from the chart in Figure 9 the sandstone monuments are far less legible than the slate ones. Just over 26% of the sandstone graves are fully legible, as opposed 95% of the slate ones. In addition none of the slate graves are completely illegible. Clearly inscriptions in slate survive much better than those in sandstone. Monuments constructed of marble and other materials total six, and all are legible, and have not been included in the above chart.

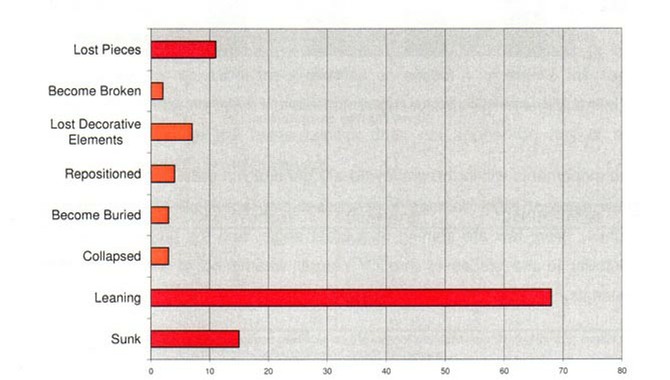

Not only was the condition of the inscription recorded, but the condition of the overall monument was noted in the survey. The chart in Figure 10 shows that by far the most common noted factor under the condition survey was that many stones were leaning; 43% of the memorials in the graveyard in fact, which is equal to 68 stones. This is partly due to the large number of headstones in the graveyard, which are prone to leaning as the soil around the grave settles. Just over 9% of the memorials were recorded as sunken. Gravestones become sunken through the same mechanism, and through ground levels rising gradually over the years. Only 11 stones were recorded to have lost pieces through breakage.

Above - Figure 10: Chart to show the factors recorded under the condition survey.

It is clear that many of the stones in the graveyard are leaning.

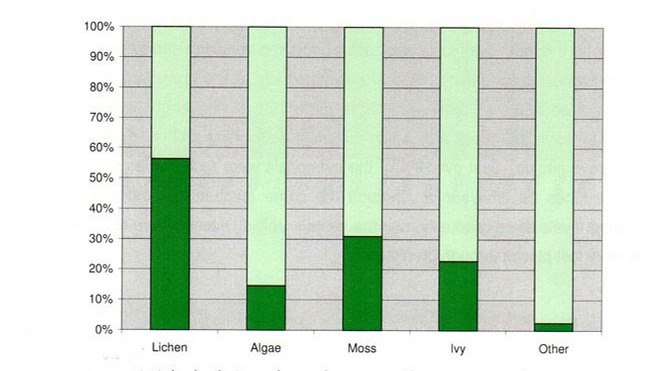

Another factor that can affect the condition of the monument is vegetation. The condition survey recorded instances of lichen, moss, algae and other vegetation around the monuments. The chart if Figure 11 shows the results of the survey of vegetation, and indicates that over half the graves have lichen present on them. This is perhaps an indication of clean air in the area. The presence of moss and ivy on a number of graves is likely to be related to a number of graves being under the canopy of trees, resulting in damper shaded conditions, ideal for the growth of these organisms. A total of 74 monuments are under the canopy of a tree, reflecting the shaded nature of the graveyard.

Above - Figure 11: Chart showing the types of vegetation present on the

monuments, and the percentage of graves that they are present on.

The monuments within the graveyard are generally in good condition. Some show signs of slight damage from grass-cutting activities, 43% are leaning slightly. Very few are leaning at a great angle, and the greatest cause of illegibility in the stones is through natural weathering of the construction materials.

6.2.2 Monuments inside the church: It is harder to apply statistical analyses to the memorials on the interior the church, as there are only 18 and they are of very different styles and dates, but can be summarised in the following points.

There are 18 memorials recorded in the church interior. Of these 11 are sandstone, and 7 are another material (mostly copper alloy plaques). Four are wall-mounted and the rest are in the floor of the church.

The earliest visible recorded date is 1668 (number 175). There are a number of graves with incised cruciform decoration, but no written date or other details (numbers 160, 161, 164). These grave slabs may date back as far as the 14th century.

Above - Pictures 3 & 4: Fragments of grave slabs with

Incised cruciform decoration, grave 161 left and 164 right.

It is possible to make out the surnames on all but one of the 15 inscribed monuments, and from this it is clear that the Lacock family were influential in the 1700’s, although the name Lacock does not appear on any of the readable monuments in the graveyard.

Above - Figure 12: Table showing the surnames readable on the Interior

monuments (note number 173 contains both Cartwright and Lacock surnames).

The chart in Figure 13 shows clearly that the majority of the monuments in the church are either readable or un-inscribed, with only five being partially readable, and none being completely illegible.

Above - Figure 13: Pie chart showing the legibility of monuments within the church.

Of the 14 memorials laid into the floor 8 have been significantly worn and damaged by footfall and other scuffing. Of the six not significantly damaged in this way, four are copper-alloy. The copper-alloy plaques throughout the church interior are in better condition than the sandstone monuments.

The wall mounted monuments are in generally good condition, with the exception of number 172; the only wall monument constructed of sandstone rather than copper-alloy. This monument, although still readable at the moment, is suffering surface flaking, peeling and blistering. The other wall monuments are in good condition, with some tarnishing being the only real sign of age.

Above - Picture 5: Monument number 172 shows signs of

damage to the sandstone surface, perhaps through damp.

7. Conclusions: The subsurface survey discovered only two features. These were in close proximity to each other, with at least one being in-situ. The absence of any fallen or buried gravestones is an interesting discovery. Although it is disappointing to not discover new stones, this in itself raises a number of questions. The absence could either suggest that older gravestone have been removed, or that stone grave markers were not used for all of the burials recorded in the parish records for the 18th and 19th centuries. The 3-dimensional digital terrain model in Figure 6 above highlights two raised areas associated with dumped material including rubble and charcoal indicating possible garden fires and management of the graveyard. The mound mentioned in the north east corner of the graveyard (L10293 on HER) appears to be one of these areas of dumped material.

The work done by the WPRG and the volunteers represents the first comprehensive survey of monuments both in the graveyard and in the church, including a condition survey and photographic record. It demonstrates that there are a number of graves, particularly those of sandstone construction, that are already partly or completely illegible, but that the general condition or otherwise of the churchyard and memorials within it, is relatively good.

Investigative work using parish records, and attempting to decipher gaps in the surviving text on graves within the churchyard is being carried by the WPRG, the information gathered in this survey should be a useful platform for this ongoing work. The information also acts as a benchmark for monitoring the condition of the monuments, and their rates of decay. The condition of stones affected by cleaning and/or the actions of maintaining the vegetation in the churchyard can also be monitored.

The following linked appendix should be used in-conjunction with the above report.

8. References and Bibliography

- Ainsworth, S., Bowden, M., McOmish, D. & Pearson, T. 2007. Understanding the Archaeology of Landscape. English Heritage.

- Bannister, A., Raymond, S. & Baker, R. 1998. Surveying. Longman, Essex.

- Bettess, F. 1990. Surveying for Archaeologists. Penshaw Press: University of Durham.

- Bowden, M. 1999. Unravelling the Landscape. An Inquisitive Approach to Archaeology. Tempus, Stroud

- Bowden, M. 2002. With Alidade & Tape - Graphical and Plain Table Survey of Archaeological Earthworks. English Heritage.

- Brown, A. 1987. Field work for Archaeologists and Historians. Batsford, London.

- Chapman, H. 2006. Landscape Archaeology and GIS. Tempus.

- Gaffney, C. & Gater, J. 2006. Revealing the Buried Past: Geophysics for Archaeologists. Tempus Publishing.

- Howard P. 2007. Archaeological Surveying and Mapping. Routledge, Oxford.

- IFA 1994 (updated) 2008. Standards and Guidance: for Archaeological Field Evaluation. Institute of Field Archaeologists.

- Lutton, S. 2003. Metric Survey Specifications for English Heritage. English Heritage.

- Menue, A. 2006. Understanding Historic Buildings: A guide to Good Recording Practice. English Heritage.

- Muir, R. 2004. Landscape Encyclopaedia: a Reference Guide to the Historic Landscape. Windgather Press.

- Mytum, H. 2002. Recording and Analysing the Graveyards. Practical Handbook in Archaeology 15. Council for British Archaeology in Association with English Heritage.

- Ordnance Survey. OS Mastermap Part 1: User Guide. V6.1.1-04/2006© Crown Copyright.

- Pevsner N. 1979. The Buildings of England: Nottinghamshire. Penguin Books Limited.

Websites:

- http://www.english-heritage.org.uk

- http://www.leica-geosystems.com

Acknowledgements:

This project has now come to a close and the following organisations are acknowledged and thanked for their contributions and support:

- St Swithun’s Church PCC (Alan Wright, Churchwarden)

- Woodborough Photographic Recording Group

- Notts CC Archaeology Department

- Cllr. Mark Spencer

- Woodborough WI

- Nottinghamshire Family History Society

- Nottinghamshire County Council Local Improvement Scheme

________________________________________________________________________________________

St Swithun’s churchyard survey of headstones

| Navigate this site |

| 001 Timeline |

| 100 - 114 St Swithuns Church - Index |

| 115 - 121 Churchyard & Cemetery - Index |

| 122 - 128 Methodist Church - Index |

| 129 - 131 Baptist Chapel - Index |

| 132 - 132.4 Institute - Index |

| 129 - A History of the Chapel |

| 130 - Baptist Chapel School (Lilly's School) |

| 131 - Baptist Chapel internment |

| 132 - The Institute from 1826 |

| 132.1 Institute Minutes |

| 132.2 Iinstitute Deeds 1895 |

| 132.3 Institute Deeds 1950 |

| 132.4 Institute letters and bills |

| 134 - 138 Woodborough Hall - Index |

| 139 - 142 The Manor House Index |

| 143 - Nether Hall |

| 139 - Middle Manor from 1066 |

| 140 - The Wood Family |

| 141 - Manor Farm & Stables |

| 142 - Robert Howett & Mundens Hall |

| 200 - Buckland by Peter Saunders |

| 201 - Buckland - Introduction & Obituary |

| 202 - Buckland Title & Preface |

| 203 - Buckland Chapter List & Summaries of Content |

| 224 - 19th Century Woodborough |

| 225 - Community Study 1967 |

| 226 - Community Study 1974 |

| 227 - Community Study 1990 |

| 400 - 402 Drains & Dykes - Index |

| 403 - 412 Flooding - Index |

| 413 - 420 Woodlands - Index |

| 421 - 437 Enclosure 1795 - Index |

| 440 - 451 Land Misc - Index |

| 400 - Introduction |

| 401 - Woodborough Dykes at Enclosure 1795 |

| 402 - A Study of Land Drainage & Farming Practices |

| People A to H 600+ |

| People L to W 629 |

| 640 - Sundry deaths |

| 650 - Bish Family |

| 651 - Ward Family |

| 652 - Alveys of Woodborough |

| 653 - Alvey marriages |

| 654 - Alvey Burials |

| 800 - Footpaths Introduction |

| 801 - Lapwing Trail |

| 802 - WI Trail |