Woodborough’s Heritage

An ancient Sherwood Forest village, recorded in Domesday

History of farming in Woodborough - by Peter Saunders

Pre and post Enclosure of 1795: This article about the history of agriculture as it appertains to Woodborough commences with a print of a household inventory taken from the Thoroton Society’s ‘Nottinghamshire Household Inventories’ edited by

P A Kennedy in 1962. This example of William Alvye’s Inventory happens to be the earliest known for Woodborough.

Early times

In the 14th century the feudal manor system was breaking up and the forced labour of the peasant was giving way in part to working for wages and the leases of land, but boon days, working for the lord of the manor still existed.

From the time of the Anglo-Saxons until the Inclosure awards, the Open Field system was used when each villager had a number of strips scattered throughout the unenclosed fields. These strips or selions, consisting of either half an acre or an acre, were ploughed in such a way as to form the ridges and furrows, now virtually gone from Woodborough but still plainly visible in other areas.

Sometimes the divisions between the strips were grass baulks but often were left as furrows to allow the rainwater to drain away. Perhaps three of the Open Fields were arable but another was usually left fallow.

The meadow allowed each villager to have a certain number of cattle on it, according to agreement by the community, and the hay meadow, after the crops had been cut, was thrown open for grazing, as was also the arable land after the corn harvest or the harvesting of other crops. With no pesticides there would have been quite a growth of grass and weeds.

Whilst forced service for the land of the manor could be enforced, it was often more satisfactory for the lord or his bailiff to hire workers for wages than rely on the grudging service of those who would have preferred to have been cultivating their own strips.

These early pictures are taken from the Luttrell Psalter, made for Sir Geoffrey Luttrell whose family lived at Irnham, near Corby Glen (Bourne) in Lincolnshire about 1320 and would probably be typical of what was also happening in Woodborough at that time:

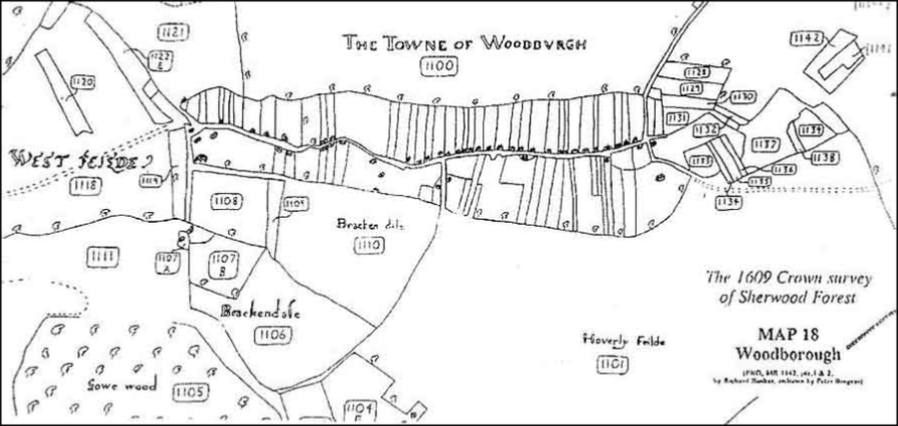

The Black Death of 1348/9 had reduced the population; estimates vary from a third to a half, so many strips of land then became vacant and could be incorporated into what had been smaller holdings. Also by agreement strips could be exchanged to make large holdings larger still which in some cases, as on the Sherwood Forest map of 1609, could be fenced off by hurdles. Also because of the Black Death, finding labour became more difficult and so landless labourers could demand higher wages.

From this map of the Open Fields and dwellings along Main Street we can trace the gradual rise of the husbandmen and the yeoman farmers, although in Woodborough the term ‘farmer’ was not in use until about 1750.

1. Shows ploughing with oxen – the plough doesn’t have wheels and the depth would be controlled by the ploughman.

2. Broadcasting the seed; there was even problems with rooks in

those days, one at the corn sack and the other taking the seed

before it is harrowed in.

3. The harrow is of wood and all square, later the supports were at

an angle to give maximum effect.

4. This one is a bit ambiguous – too many sheaves for a stook to dry the corn – perhaps they are getting ready to load them onto a cart.

Towne Street section (Main Street) centre of Woodborough - Richard Bankes map 1609.

The Open Field system was in existence in Woodborough right up to the Inclosure award of 1795 when the detested tithes to the Lords of the Manors and the clergy were abolished, and the tithe owners awarded land in lieu. Before Inclosure in Woodborough it was a case of subsistence agriculture for the majority of inhabitants. Hopefully you grew or reared everything that was needed to survive. What you couldn’t grow you bartered, lent or borrowed. Debts owing to or owed by the deceased as listed in inventories show a whole range of things borrowed or lent.

Spinning and Weaving - In the 16th-18th centuries people often never travelled outside of their village. If you needed new clothes or bed linen you had to make your own. You couldn’t even buy ready-made materials to make up these articles. It was a case of growing the necessary crops or obtaining sheep’s wool, spinning the fibres to make a yarn and taking the yarn to the village weaver to make the articles you require.

Weavers were the most frequently mentioned tradesmen in the 16th and 17th centuries in Woodborough, so there must have been plenty of spinning done by the women of the village, and perhaps by some of the children. A number of inventories contained spinning wheels of various descriptions. Their use, whether for wool, flax or hemp was often unspecified, but occasionally a wool wheel or a tow wheel was mentioned.

Flax - Nowadays flax, a 3 to 4 foot high plant with blue flowers is grown for two reasons, for the stem fibres which when processed can be spun and woven into linen or for the seed from which linseed oil is obtained.

Flax would have grown quite satisfactorily in the loamy soil of the Woodborough valley and the inventories of the period show that this indeed was the case. A quarter of an acre of flax had to be grown by law if a person had more than 60 acres of ploughed land, but it would seem that more than the obligatory amount was grown in Woodborough, judging by the amount of flax, tow and linen cloth in the inventories. One can imagine some of the strips in the Open Fields in the early summer, a tight mass of flowering flax plants, sown closely in order to achieve the length of stem and the straightness of the stem required to obtain the best fibres. In order for the flax to be harvested, the plant stems were pulled, not cut, as the fibres needed for the making of linen extended from the root to the top of the plant. Length of fibre is one of the important qualities of flax. The fibres are also strong and absorb water readily, hence their use for modern tea-towels.

They also conduct heat well, giving that lovely cool feeling experienced with linen sheets. The bundles of fibres, when pulled, were stacked to dry as were the sheaves of corn in Woodborough before the advent of the combine harvester.

The fibres then had to be separated from the remainder of the stem material. This was done firstly by a process called ‘retting’ i.e. allowing the bundles to soak in water long enough for the stem material to decompose whilst leaving the strong fibres intact. Retting could be carried out either by laying the flax on grass and allowing the dew or rain to moisten it or by immersing the flax in ponds or running water. When the retting had taken place the bundles of flax would be hung up to dry, probably in the ‘hinge-houses’ or hinging houses frequently mentioned as being among the farm buildings. Next the flax stems had to be broken i.e. getting rid of the decomposed straw stem, and this was achieved in Woodborough using a ‘brake’ mentioned in several inventories. A brake was usually a board with, or against which, the bundles of flax were beaten to remove as much of the unwanted stem as possible.

The next stage was the use of ‘heckle’ which was a type of trestle with rows of pointed nails or pins protruding from a board along the top edge. The bundles of flax were pulled across the pins which served a three-fold purpose. Firstly it removed the remainder of the unwanted straw, secondly it removed the shorter flax fibres known as ‘tow’ which could also be used, and thirdly it helped to align the longer fibres ready for spinning.

The adult female population of Woodborough would have been adept at using the spinning wheel for spinning and their early wheels would probably have been turned by hand, one hand turning the wheel and the other teasing out the carded wool, flax or hemp from a distaff into a long continuous thread. Flax would probably in early times have been spun using a spindle and whorl until the introduction of the flyer spinning wheel which allowed the flax fibres to be twisted and wound on to the bobbin at the same time. Later the treadle spinning wheel was developed allowing the spinner to use hands for drafting the fibres. A ‘reel’, also mentioned in our inventories, rather like the hub and spokes of a cartwheel, was used to wind the linen thread from the spinning wheel’s bobbin to form a hank of yarn. The circumference of the reel allowed the winder to work out how much yarn was in each hank or ‘slipping’. The younger members of the family probably wound the yarn into hanks whilst mother or an elder sister was engaged in the spinning.

As no looms are mentioned in the inventories, other than the inventories of the weavers, it would seem that all the yarn was taken to the weavers to be made into cloth.

Hemp - Hemp, a much taller plant, was also grown in the village and the fibres of hemp and the tow or shorter fibres of the flax were both spun, and the yarn used in making hemp and harden cloth which were rougher and coarser than that made from the best flax yarn. Items such as cart cloths, wall painted cloths, sacks, window and winnowing cloths, ropes and halters would be made from tow or hemp, although most households in Woodborough possessed some hempen and harden sheets as bed linen.

Wool from the village sheep had to be combed in order to remove burrs and weed seeds and it was then ‘carded’ using ‘wool cards’, boards covered with nails or pins. The wool was laid between the boards which on being stroked in opposite directions lined up the wool fibres for spinning. Woollen cloth would have been used for blankets, coverlets and much of the clothing worn by the majority of Woodborough people.

The russet cloth mentioned in some inventories and valued at 1s.3d a yard in 1578 would almost certainly have been woollen. ‘Carsey’ with its variety of spellings and originating from Kersey in Suffolk, was a coarse, narrow woollen cloth, usually ribbed and valued at 1s.7d a yard. Linsey–wolsey was a cloth with the warp threads of linen and the weft threads of wool, and both Carsey and Linsey-wolsey occurred in Woodborough inventories.

Webs of cloth, linen, wool and hemp are frequently listed, a web being a whole price of woven cloth from the loom waiting to be made up into articles of apparel or for household use.

The ‘ticking’ in the inventory of Mark Hather, 1719 would most probably have been made of linen and used for covers for mattresses and pillow cases (pillowberes in the inventories). Wool unsuitable for spinning either on a wool wheel or tow wheel would no doubt be used to stuff the flock mattresses commonly used.

The weavers probably worked in the area between Beckside and the Nags Head, living and working on the north side of the Main Street and using the land opposite. The deeds of several houses where Bill Alvey lived are recorded as being built on ‘Tenter Close’, a tenter being a frame on which the weaver stretched his cloth, possibly to stop it going out of shape after it had been washed or dyed. The stream running along the south side of Tenter Close would have helped to make this a suitable area for weavers to ply their trade. The weavers, judging by their inventories, did not seem to have kept any stocks of yarn or webs of cloth, suggesting that the weaving was done to order, as and when the housewives of the village took their spun yarn to be woven.

Rye - Firstly, early quotes from E.M. Trevelyan’s Social History of England:

Until the 18th century it was not possible to ripen enough wheat to feed the whole population. Oats, wheat, rye and barley were all grown, some more, some less, according to the soil and climate. In all parts of England the village grew a variety of crops for its own use, and its bread was often made of a mixture of different kinds of grain.

Writing in 1577 Harrison said “The bread throughout our land is made of such grain as the soil yieldeth, nevertheless the gentility commonly provide themselves sufficiently of wheat for their own tables, whilst their household and poor neighbours in some shires are forced to contend themselves with rye or barley, yea, in time of dearth many with bread made out of beans, peason, or oats and some acorns among”.

In about 1605 it was written “The English husbandmen eat barley and rye brown bread and prefer it to white bread as abiding longer in the stomach, and not so soon digested with their labour, but citizens and gentlemen eat most pure white bread”.

By the time of George I c.1720 English agriculture had improved so far that more wheat was sown than in medieval times. Wheat was reckoned at 38% of the bread of the whole population, rye came next and barley and oats a good third or fourth.

So what about the growing of rye in Woodborough? The earliest record of rye being grown is 1601, and although it is difficult to be certain it appears that whilst wheat was often grown as a separate crop, a significant amount of wheat and rye were sown and grown together. For example, John Clarke in 1662 had one acre of wheat and rye valued at £3 whilst George Clarke 1664 had an acre of wheat and rye worth £2 10s. John Bould, gent, 1628, had in his corn barn wheat and rye in the straw (un-threshed) worth £3 4s.

Richard Truelove, 1635, had listed under ‘corn in the field’ all white corn and barley, wheat, rye and oats valued at £26 16s. and Mark Hather, 1745, had a wheat and rye stack worth £3 10s.

In the early years, say 1500, whilst the gentry and better off yeomen and husbandmen in Woodborough would probably have eaten predominantly white bread, the cottagers and labourers would have eaten a maslin bread, i.e. a mixed grain bread of wheat and rye. As we get to the last of the inventories in 1758 which mentioned wheat and rye, more people would have been eating bread made predominantly with wheat. After Inclosure it seems unlikely that rye was grown in Woodborough although the Rye Close is mentioned in the Inclosure Award. At just over 8 acres it was what we know as the Park – Stanley Wood to Main Street (Park Avenue).

Crops on the ground and in store - The amount of land put down to the various crops is sometimes difficult to estimate because of the way the inventories were written. For example, many of the early inventories just gave a value for ‘corn on the ground’ or ‘all the hay and corn’ with no indication as to variety, whether wheat, barley, rye, oats or a mixture, particularly of wheat and rye which were often sown together.

Sometimes it didn’t state if the crop was in the barn, stackyard, or field. Richard Crofte’s inventory of 1601 mentioned wheat and rye and barley in Westfield, Shutfield and Brackendale, worth £23, barley in Eastfield worth £12, the peas and oats in Horlayfield worth £13 6s. 8d and the fallows being valued at £10.

Although Richard’s inventory shows some variety of crops and that the fallow ground was valued, it does not help to assess the proportion of land given to each crop.

Left: Stackyard adjacent to Nether Hall (also known

as Old Manor Farm), Woodborough, in 1949.

One early acreage in the inventory of John Clarke, 1662, who had one acre of wheat and rye worth £3, one acre and a half of barley, also worth £3, and three acres of peas worth £3, showing that his acreage of peas was equal to that of his cereal crops. The value of his peas per acre was less than half that of the corn.

Philip Lacock, 1668, had 20 acres of barley worth £35, 4 acres of wheat worth £7 and 8 acres of peas worth £8.

Left: Pea harvesting near Roe Lane. - Right: Pea picking at Grimesmoor both Woodborough scenes dated 1946.

Peas seem to have occupied more ground than all the other cereals put together so they must have played a very important role, either as food for humans, animal food or probably both. As far as food for people is concerned, they could be used for pease-brose made by pouring boiling milk over oatmeal, peasemeal or a mixture of both, peaseporridge, pease pudding and pease soup. The peasemeal could also have been used as an additional ingredient for rye bread or for thickening a stew. There was so great an acreage that it must have been used as an ingredient in the food for livestock.

From the inventories:

- Nathaniel Foster, April 1669, had 4 quarters of pease at 16s a quarter – value approximately £8 and 24 acres of pease at 20s. 8d an acre valued at £32 compared to £24 for 12 acres of wheat and £3 for 4 acres of oats.

- John Lee, framework knitter September 1704, had peas in the stack worth £6.

- Henry Clemson, yeoman, March 1718, had pease threshed and un-threshed worth £10 5s and 5 acres of wheat sown worth £13 10s.

- John Thorpe, May 1730, had 6 acres of pease and oats worth £6 and 6 acres of wheat and barley worth £12.

As late as November 1758 – towards the end of detailed inventories, Richard Wheeler has pease in the framed hovel worth £6 10s and old peas at £2 10s. It seems that pease and oats were often sown together, if so they could be ground as a meal for human and livestock use. Did they know that growing pease helped to improve the soil?

Farm implements – carts - Carts would be required for all the usual farm activities, transporting manure to the Open Fields and bringing the crops of corn, hay and peas back to the homestead or barn. The roads around Woodborough pre-Inclosure would probably have been no better than bridle tracks, rock hard ruts in summer and autumn, deep in mud and pot-holes in the winter and early spring.

Carts are mentioned in the earliest inventories:

- William Alvye, husbandman, having two in 1567.

- In 1589 Nicholas Alvey possessed ‘one iron-bound waine and one bare wain’ valued at £1 10s.

- Robert Lightladd, 1578, had ‘two bounde carts, whele timber and plowe timber’.

- Henry Chaworth, gent, 1640, had ‘a waine, a cart and 2 sleades’.

- Tumbrils, cart which incorporated a tipping device, were possessed by Nathaniel Foster, 1669.

- Mark Hather, 1719, had a pair of tumbrils and a wagon valued at £6 5s.

- The wagon and cart of Samuel Lee, yeoman, 1632, were valued at £7 10s.

Cart ropes are mentioned in several inventories, for tying down the hay or corn on the carts and wagons, and the hemp previously mentioned would have been used for strong ropes for carts and horse halters.

Sleds - The construction of sleds would be much easier and cheaper than that of wheeled vehicles, wheel making being such a specialised craft. Where it was difficult to use carts and wagons such as on the slopes towards Ploughman Wood, sleds would probably have been used. The owners of the Upper Hall would have been able to use sleds in winter on the frozen ground to bring the timber down from Woodborough valley to their sawpit at the Hall.

Christopher Alvie, husbandman, 1667, possessed ‘two iron-bounde carts, a cart bodie and a sleade’. Woodborough farmers in the 1930’s had carts, tumbrils and wagons and the Old Manor had a moffrey, a cart which could be converted into a wagon for carting hay or corn. Moffreys were used in Lincolnshire.

Livestock - Horses - Horses had apparently replaced the oxen in Woodborough at a surprisingly early date. An inventory of William Alvye, husbandman, 1567, lists four horses, one colt and one old mare. Horses seem to have been kept in good numbers for ploughing, harrowing, carting and other farming tasks as well as for riding to travel round the countryside and as pack animals. There are references to saddle horses and carthorses and George Clarke, 1578, had a grey filly and a black filly as well as several other horses.

There would be a considerable strain on both cart wheels and cart bodies and the wheelwrights would certainly have been kept busy, although the craft of wheelwright is not specifically mentioned. Occasionally carts are listed separately to distinguish iron-bound ones, that is, those with iron hooped wheels from those that were not. It is unclear whether the iron-bound wheels had the rim shrunk on in one piece as was still practised in the village in the 1930’s, or perhaps nailed on in sections.

Right: A typical 1900’s

horse and cart.

With poor trackways, small amounts of goods would have been carried by horseback as there are references to a pack saddle and panniers. No doubt salt from Cheshire, via Salterford Dam, would have arrived in Woodborough by packhorse.

Ladies would also have travelled on horseback as Henry Chaworth, gent, 1640, had a side saddle and a pillion and cloth.

Horses were bred as a matter of course in the village, stallions and geldings were referred to as ‘horses’ as distinct from mares.

A number of inventories include foals, colts, yearlings and fillies but the word pony does not appear until 1742. Husbandmen and yeomen had anything up to eight horses but the gentry, with their enclosed lands, seem to have had the largest number.

- Charles Lacock, gent, 1683/4, had two saddle (riding) horses worth £15, six carthorses valued at a total of £41 and two young horses worth £5.

- Nathaniel Foster, gent, 1695, had fifteen, comprising ten horses and mares and five foals, with a total value of £47.

The average value of a horse in 1578 was about £1 6s 8d and had risen to about £4 by 1750, the value naturally depending on the horse’s age and condition. It is interesting to note that John Lee, 1682, whose trade was described as ‘silk stocking framework knitter’, also ‘farmed’ and had a fair amount of livestock including two fillies, a horse, two mares and a gelding – the only one so described.

The occurrence of a ‘half-horse’ in the inventory of Joan Sugar, 1590, is puzzling until we arrive at the Will of William Glover, 1594, who leaves a horse to be shared by his wife and his eldest son.

Cattle - The generally accepted idea that the majority of cattle were killed off in the winter because of the shortage of fodder does not seem to have applied in Woodborough:

- Charles Lacock, who died in February 1683/4, had 14 cows and a bull, 12 young beasts, 6 yearling calves and 10 young calves as well as 173 sheep. His hay was valued at £20.

- Henry Clemson, who died in March 1719, had 9 beasts and 2 calves.

- Richard Wheeler, who died in April 1686, had 11 beasts and 8 calves with hay still in the barn.

- Nathaniel Foster, October 1695, had obviously prepared for winter fodder, with hay valued at £26 to feed his 9 cows, 2 bulls, 10 young beast and 8 calves. (Beasts in the inventories only applied to bullocks).

Both Charles Lacock of the Upper Hall and Nathaniel Foster of the Nether Hall would have run quite big estates, probably with many labourers and servants living-in or living in neighbouring cottages, who would need milk and the butter and cheeses made from it.

They would also have supplied the elderly, the village craftsmen and those without land to keep a cow, with milk, butter and cheese. As there is no mention in any of the inventories of food for cattle, apart from peas and cereals, it would appear they would rely mainly on hay for fodder. (Turnip Townsend, 1740 – Coke 1780). The average value of a cow in 1600 was about £1 13s 4d, which had risen to about £2 10s by 1700. How did enclosure affect the raising of cattle in the village? With the extra land granted to them in lieu of tithes the three manors would have been able to increase their stock. Now that the village was divided into small fields the lesser land owners could, as well as having some arable land, have put some down to pasture, using some grass land for hay for fodder for their horse/s and cattle for the winter, or use it as grazing for horse and cattle.

Turning to more modern times, there were few large herds of cows such as in the Severn Trent farm at Bulcote. Drings on Shelt Hill and Baguleys at the Old Manor had herds of cows. Probably Stevensons at what is now Cottage Farm, Dunthornes on Main Street and the Middle Manor would have had a house cow or two. Mannie Foster’s accounts show the sales of bullocks, steers and heifers between 1945 and 1953 all were sold to the Ministry of Food. Sometimes the bullocks were bought at market to be fattened; sometimes calves were purchased from Drings for £3 or £4, presumably male calves that in modern large herds would be killed at birth. Mannie Foster’s accounts show sales of 6 heifers in July 1950 for £314, and 8 steers and 2 heifers in October 1953 for £745.

Sheep - Sheep are mentioned in about half of the Woodborough inventories. From the number of references to wool kept in the house, to woollen cloth and implements used in spinning and weaving, it would appear that sheep were kept more for their wool than for food. There are no references to lamb or mutton as food, although bacon flitches occur regularly and beef or ‘hung beef’ on several occasions. No doubt older sheep not fit for breeding were killed and eaten but by that time were probably only be fit for stew or broth. Lambs, although often mentioned in Wills were only itemised in two inventories.

John Thorpe in May 1730 had thirty-five sheep and twenty lambs valued at £11 and James Cliff in October 1742 had twenty-one sheep and seventeen lambs worth £10. It was often the practice of yeomen and husbandmen to leave a ewe and a lamb to their godchildren or grandchildren in their Will.

In the period 1567-1742 there were twenty flocks which contained 38 or more sheep, the highest numbers being the 173 sheep of Charles Lacock, 1683/4, 107 of Nathaniel Foster, 1695, and 90 of Richard Wheeler, 1722/3. The average number of the flocks of eight husbandmen from 1567/1667 was 50. The two largest flocks both belonged to the gentry whose land would have been enclosed, but I feel sure that the other large flocks of the yeomen and husbandmen would have been on enclosed land even though this was before the official Inclosure of the village.

In earlier times it was the practice laid down by the lord of the manor that all the sheep of the village people had to be folded in winter in the lord’s fold which was to his benefit and the villagers’ detriment that he obtained the manure. However by the 17th century the yeomen and husbandmen folded the sheep by means of fold fleaks mentioned in many inventories in their own yards and so retained the manure for their own use. The same thing probably happened at lambing time. With no artificial fertilisers, manure from all livestock was very valuable and was priced on most of the land ‘farmers’ inventories.

As to modern times, there were very few sheep in Woodborough although there may have been some at the Old Manor. It was when Kirkham’s moved to Bank Hill Farm numbers increased. Could it be that apart from some pre-war permanent grassland it was more profitable to have arable land?

Pigs (swine) - The majority of families on Woodborough in the 16th and 17th centuries kept a small number of pigs, usually 2-4, although George Clarke, 1578, had 12 swine valued at £2 2s 6d. Generally the value of a pig was slightly more than that of a sheep. The fact that all parts of a pig could be eaten, together with the fact that ham and bacon could be cured and eaten during the winter months no doubt enhanced the value of the pig. Christopher Alvie, 1617, had a ‘sow and pigs’, presumably a sow and piglets, and 4 swine ‘shotes’ and Richard Truelove had 2 shotes valued at eight shillings. Shotes were either un-weaned or castrated pigs, glossaries differ as to the meaning.

William Oldney’s inventory, May 1615, contained eleven swine and also eight bacon flitches, could they all have been for his household’s consumption? Perhaps he had live-in workers and servants needing to be fed.

Swinecotes are mentioned in the inventories of Henry Bennett, 1607, and Henry Alvey, 1616, and Edward Foster had ‘fat swine and field swine’. The fat swine might have been restricted to stys and received additional household scraps whilst the field swine would forage for themselves by day and be kept in the swinecotes at night.

As the Upper Hall and Middle Hall ‘owned’ the only woodland in the village it is unlikely the villagers’ pigs were allowed in them to eat the acorns as was the case in the true forest.

In the 1800’s the framework knitters were encouraged by the Male Friendly Society to have an allotment to provide food for their families and extra for a pig. In more recent times, say the 1930’s, most smallholders in the village would have kept a pig or two. Mr Snodin kept a pig and his wife used to boil up the small or ‘pig’ potatoes in the copper in the outhouse to mix with the pig-meal. Mr & Mrs Worthington, Elise Leafe’s maternal grandparents, living at Beck Side next to Elsie Middup’s, always had a few pigs in a sty that backed onto the dyke.

On pig-killing day, Mannie Foster’s Uncle Peter could be seen wheeling his flat barrow along the village street with his knife on a length of twine and you knew that somewhere there would be a copper-full of water on the boil.

In 1918 he persuaded the school managers to obtain part of the Old Recreation Ground belonging to Mr Burton for a school garden which he divided into eight plots. As well as training in the use of tools etc. land measurement was also undertaken using a Gunter’s chain and visits were made by the older boys to local farms. Both boys and girls were allotted to a garden, each with its own set of numbered tools consisting of spades, forks, rakes, hoes and mattocks. These were checked by a responsible boy after each session to make sure they were clean.

Both sickles and scythes occur (see right), it would have been back-breaking work cutting corn with a sickle, although one hand could hold the crop whilst the other hand used the sickle. Hay was cut with a scythe, but when used for cutting corn the scythe was often fitted with a hazel attachment so that the following worker could more easily bind the corn into sheaves using straw bands. The wimble was rather like an old fashioned brace and bit; it could have been used for boring holes in wood but usually had a hook and appears mainly to have been used for making straw bands for sheaves and for making rope out of flax, hemp or straw. In 1916, when Mr Saunders came as headmaster, Woodborough was mainly an agricultural village and he obviously thought that as many boys leaving school at 13 would be working on the land so some training should be given at school.

The Fallows and Manure - The Fallows - The fallows or fallow land was land which was left uncultivated for a year, (what is now called ‘set-a-side’). The idea in the time of the Open Fields was that one field in rotation would be rested in order to regain its fertility. They do not seem to have realised that the beans and peas which they grew would help to put nitrogen back into the soil. Some enlightened people may have realised it but the tradition of leaving one field fallow remained.

The first reference in the Woodborough inventories to the fallows is that of:

- George Clarke, 1578, when his ‘fallows were ready to be sown’,

- Richard Croftes, 1601, a wealthy husbandman had crops in West Field, Shut Field, East Field, Brackendale and Hawley Field and his fallows were valued at £10.

- Two copies of the inventory of William Foster, 1620, a poor cottager, have survived, one very poorly written on paper and another on parchment in an educated hand, most probably by a Southwell scribe for their records, and they valued his fallows at 5 shillings. He probably had just a few strips of land in the fallow field.

- Richard Johnson, 1632, another quite well-off husbandman with assets of £120, had his fallows valued at £6 13s 4d.

When both the acreage and value are given we can work out the value per acre, and assume that this was the value of land in Woodborough at that time.

- Another George Clarke, March 1664, and a yeoman, had one acre of mixed wheat and rye worth £2 10s but his five acres of fallow were valued at £5, giving a value of £1 per acre.

- Charles Lacock of the Upper Hall, a very wealthy gentleman in February 1684 had nine acres of wheat worth £15 and his eleven acres of fallow were value at £14 or just over £1 5s an acre.

- Nathaniel Foster of the Nether Hall, another wealthy gentleman in October 1695, had 15 acres of fallow value at £19, again about £1 5s an acre.

In the period between 1728 and 1745 there are several references to ‘Clotts’ which must refer to stubble left on the fallow ground.

- James Cliffe in October 1728 had four acres of barley and wheat clotts value at £6 and

- John Thorpe in May 1730 had ‘six acres of fallow ground with manure to lay upon it’.

- Mark Hather in March 1745, yeoman, had ‘the barley clotts upon the fallows valued at £4’.

Leaving the barley or wheat stubble, together with the weeds and the manure would have benefited the soil structure when ploughed in. Leaving one Open Field fallow may have allowed the workers more time to concentrate on their other crops in the Open Fields and on their holdings.

Unfortunately the Woodborough inventories ceased about 1760. However, when the village was enclosed in 1795, each landowner would have been able to decide what to do in his own fields. With the loss of the Town Meadow many would probably have put their fields to pasture and for hay instead of leaving them as fallow ground.

Little land was left uncultivated, and certainly from 1939-1945 during World War II, fuller use was made of the land as it must have been during World War I.

Manure - Before horses were in general use in the village, and with no artificial fertilisers, manure would have come from the folding of cattle and sheep, and some swine would have been kept close to the cottage or homestead. During the winter stock would probably have been kept in the yard or under cover where straw might be laid down to bed the animals. The manure, which the appraisers of the inventories always had difficulty in spelling, was invariably valued in the inventories and from the prices given it is obvious that it was a valued commodity. Later with the greater use of horses for farming and riding they would have been stabled at the homestead and were a welcome additional source of manure.

In the inventory of:

- John Thorpe who died in early May 1730 it states ‘six acres of fallow ground with the manure to lay upon it’.

Several inventories had the value of the manure in the yard, mainly in the months of December to April valued at about £2.:-

- Nicholas Lee, April 1670, had ‘all the manure in the fold yard valued at £2 10s’, his namesake in 1667 had manure in the yard valued at £4 and

- William Shephard, 1661, says in his will that his wife is to have the remaining sheep to maintain her land by folding them, and the wool for her own use.

In a mainly agricultural community it was necessary to ensure all your goods were distributed fairly to the farming sons and in his Will, Walter Lee, husbandman, 1656, left all his manure in the yard to his son Thomas.

Fold fleaks and the fold yard are mentioned in many inventories. In the 1920’s/30’s and at least up until World War II cattle at the Middle Manor would be kept in a covered yard with the young stock in loose boxes round the crew yard, e.g. Mr A Dunthorne’s barn on Main Street. The manure from the horses and the milk cows would often be in an open steaming heap in the crew yard, but if the stock were in the covered yard or loose boxes, layers of straw would be put down and regularly added to, often it was quite deep, until it could be put on the land as manure when the cattle were put out to grass. The manure in the crew yard could be put on the land in the winter, a job with hedging and ditching, or later in the spring. It was usually spread from the back of cart or tipped in heaps from a tumbrel to be spread by hand later.

The demise of the horse in agriculture, the railways also employed an enormous of number of horses, meant that a valuable source of manure was lost. When I was a teenager in Woodborough I did a lot of gardening but I could never persuade anyone to sell me any manure. They said it was like selling your birthright.

Fertilisers - There was always a pile of bags of soot, the pile varying according to the season, on the farm track between the Little and Big Sickes, a few yards in from the Lingwood Lane gate. With coal fires in those days there was plenty of soot to be had. Presumably it also provided an extra source of income for the Nottingham chimney sweeps. It had to be left for some months to weather as otherwise it would have burnt any young plants with which it came into contact. Usually by the time it had weathered, the sacks had disintegrated. It was put around young cauliflower and cabbage plants to deter slugs after the plants had been set out in the field. The Manor must have used a lot of soot for Mannie Foster’s accounts show that in February 1946 £20 16s 6d was paid for soot and in August of the same year £18 10s was paid for two loads.

The principal fertilisers used were Kainit and basic slag (known as Bassic Slag in Woodborough). Kainit consisted of magnesium sulphate and potassium chloride and was associated with deposits of salt whilst basic slag was a bi-product of the basic steel making process and was rich in lime. However according to Mannie Foster’s account, considerable amounts of money were paid for fertilisers at the Manor. Amounts paid to Fisons were £93 5s in 1947 and £217 in 1951. Other bills for fertilisers were for £242 in 1946, £244 and £200 in 1950, £17 for a ton of potash and £17 for sewerage sludge. This would be when the Nottingham sewerage farm settled the sludge in banked open fields at Netherfield and also at Bulcote before the modern methods of sewerage disposal were developed.

Agricultural Implements - Ploughs and Ploughing - There is no doubt that in earlier times oxen were used in Woodborough for ploughing in the Open Fields but by the end of the 16th century practically all the ploughing was done using horses. The ploughs and gears of Nicholas Alvey in 1589 were valued in his inventory at five shillings but his yolk of oxen for pulling his plough was valued at £3 16s 8d. A yolk did not necessarily mean a pair, Nicholas also had horses so one wonders if the teams were mixed as in an illustration in the Gorleston Psalter of circa 1310-25, or whether oxen pulled one type of plough and horses another.

Richard Croftes, in 1601, a prosperous Woodborough husbandman had two ploughs, two dozen plough handles and six plough heads. He also had 16 shelfboards (or shellboards) and Thomas Weir’s inventory of 1616 includes 9 shelfboards.

These shelf or shelfboards could either have been the wooden mouldboards for the plough, the part which actually turns the soil over, or they could have been extra boards or shelves which were fitted onto the sides, front and back of a wain or cart at harvest time to enable them to carry larger loads of corn or hay. Glossaries differ in meaning.

Right: A typical hand guided plough from 1923.

Frequent references are made to coulters and shares, parts of the plough which were made of iron and so long lasting and more valuable. The coulter, like a knife, cut the soil so that it parted cleanly and the share was the metal point fastened to the mouldboard and taking the most strain.

‘Plow timber’ occurs frequently in the inventories and would be used for the plough beams and handles which were liable to break under stress, or may have been the actual spare parts for the plough. ‘Plows and their gears’ could include the swingletrees and traces for attaching them to the horse’s collar:

- Philip Lacock, 1668, had ‘five plowes and plow timber’ with the coulters and shares.

- Nathaniel Foster, 1669, had cart timber and plough timber.

- William Pickard, 1675, had ‘three plow beames’, and

- Robert Owell, 1669, had plough timber and felloes, but as he was a carpenter, he was probably a maker, user and supplier of them.

There is no mention of wheels for ploughs, it could be that they were not needed for the type of plough being used, the depth of furrow being controlled by the pressure on the plough handles.

Harrows - After ploughing, the soil needed to be broken up so that the seed could be sown evenly. If the ploughing was done in the autumn the frost would break up most of the clods. If the land was ploughed again in the spring a harrow was used to create a better tilth. Harrows at first would have been made of wood with metal tines, but later of iron entirely:

- Robert Lightlad, 1578, had an iron harrow.

- Thomas Weir, 1616, still had an ox harrow.

- Christopher Alvey, 1617, who, by the size of his inventory was an extremely prosperous husbandman, had two iron harrows.

From 1669 harrows were usually referred to in the plural, perhaps they had learned to gang harrows together depending on the number or horses used and the nature of the soil.

Rolls - Horse-drawn rolls were a common sight in Woodborough in the 1930’s either of the flat or Cambridge type but they are rarely mentioned in the early inventories although:

- Thomas Weir, 1616, had ‘one roule’ listed with his ploughs and harrows.

- Robert Wheeler, 1758, had ‘a rowl’ worth five shillings.

Chain harrows, consisting of chain-linked loops of iron were used in the 1930’s, and I expect are still used in the spring to tear apart old tussocks of grass and level mole hills in pastures.

The effects of Enclosure - It was the 1795/8 Inclosure Act which probably caused the greatest upheaval in Woodborough’s agricultural life. The enclosure of land in the village had been going on in a quiet way for some time as the yeomen and husbandmen had gradually been increasing their holdings.

If holders of neighbouring strips had become too old or disabled to cultivate their land it gave the opportunity for the more wealthy or foresighted landowners to purchase the strips or even exchange strips in order to obtain blocks of land which they could then enclose.

The Inclosure Act was to the benefit of some small landowners but a disaster for others. Those village people who rented their strips in the Open Fields found that the owners had been allotted bigger compact areas which they could sell to the highest bidder which the bigger landowners could afford.

The poor holders of selions, now given a block of land found it had to have a quickthorn hedge in the middle of a double rail fence and drainage had to be made. Many could not afford to do this and so sold their land to become cottagers or labourers. Fencing their land wasn’t so expensive if it was surrounded by other people’s fields so the expenses of fencing and ditching could be shared.

There were many disadvantages of the Open Fields system. One was drainage on sloping ground caused by the water running down the valleys of one furlong onto another, taking with it the top soil and any manure on it. Timber couldn’t be grown as the cattle and sheep were put on the land after harvest for communal grazing.

Access was difficult as the workers were forced to dog-leg across the headlands of different furlongs, often these headlands being cropped by some less fortunate member of the community. Travelling between strips in different parts of an Open Field and between the different Open Fields was very time consuming and is reputed to have been a cause of indolence and that self-sufficiency was the only goal.

An elderly neighbour, or an inefficient one, or one who was just bone idle could allow his weeds and rubbish to encroach on your strips and there were the inevitable arguments over encroachment of strips and taking in the land of others. All crops had to be sown and harvested within specified times, if you were late in preparing your land or sowing your crop, it might be too late to harvest it before the communal grazing began.

Grazing in the Town Meadow limited the number of animals you were allowed to keep, and during March parts of the meadow were closed until after the hay harvest. No building was allowed on the Open Fields so everyone had to transport their tools, and take their crops to their own barns or outbuildings across muddy tracks, a waste of time and energy.

Benefits - For the Upper Hall, now that hunting in the enclosed villages in Sherwood Forest had ended, the forested and waste lands could be farmed and so farmsteads were being built and leased out to tenants. In Woodborough valley Wood Farm, Park Farm, Stoup Hill Farm and Bank Farm were built.

As far as the lesser landowners were concerned, they could decide which field or fields were to be pasture or arable and learn what amount of stock a field could support. They could decide whether to concentrate on cattle, sheep, cereals or other crops. They could plough their land in a direction which would eliminate run-off of soil and manure, and dig a pond if necessary. They could plant hedgerow trees, instead of relying for timber on the woodlands of the Middle and Upper Manors, and if they so wished they could build a hay or corn stack, or even a barn and a shed for milking on their fields. Most of all it eliminated the continual trudge from strip to strip and Open Field to Open Field, enabling them to use their time and labour much more efficiently, and the use of wide, if poorly surfaced roads.

The Industrial Revolution - At about the same time as the Inclosure of Woodborough, another important effect on village life was the Industrial Revolution. After the inventories of Hargreaves’ Spinning Jenny, 1767, and Crompton’s Mule, 1775, spinning moved from the cottage industry to the factory and the weaving process also went from the village weaver to the factory, particularly with the advent of steam power. With the development of the cotton mills in Lancashire and the woollen mills of Yorkshire, the use of spinning wheels and the era of the village weaver would have been dying or already dead.

In the Inventory of Mark Hather, 1719, we find reference to ‘4 old spinning wheels’, suggesting that they were probably no longer used. The last weaver in Woodborough was probably John Morley who died in 1729, but his Will does not state to whom he left his weaving looms and equipment mentioned in his Inventory. With the introduction of cotton cloth there was less need for linen. Cotton cloth was cheaper to produce, lighter to wear and easier to launder. Growing of flax and hemp in Woodborough probably ceased in the middle of the 18th century.

The larger landowners in the country such as Turnip Townsend, Coke and Bakewell, had already begun to improve their crops and their livestock. After enclosure the fact that smaller landowners could set aside fields for pasture, some for grazing and some for hay, and some as arable land, meant that livestock could be kept in better condition throughout the winter months.

The larger landowners could not rely on the labourer’s use of sickle and scythe to harvest their crops and encouraged and financed the development of different types of horse-drawn machinery.

Grass Mowing - Before the advent of the horse-drawn mowing machines for hay-making, teams of men used scythes to cut the hay. It was then turned by hand for a few days if the weather was fine and then put into windrows and later into haycocks so that it was easy to load onto the cart. The horse-drawn mowing machine came along in the early 19th century and the swath-turner in the middle of the 19th century, about 1860. The side delivery rake would put the rows of cut and dried hay into windrows to be followed in about 1890 by the ride-on horse-drawn rake which by pulling a lever, the rider could raise the tines when a sufficient amount of hay had been collected. Mr Arthur Snodin, with his smallholding next to St Swithun’s Church, was still using a horse-drawn rake in the 1930’s.

Stationary steam and tractor-drawn balers first appeared in the 1930’s but tractor-hauled mobile balers didn’t really come into general use until after World War II.

Above: A side delivery grass cutter.

Below: A horse drawn grass cutter in action.

Above: A horse drawn ride-on rake.

Below: Peter Saunders the author

of this article (boy in white shirt).

Reapers and reaper binders - The problem with the first reapers was how to cut the blades of corn and pull them onto the cutter. It was not until 1831 that a man named Bell derived a cutter with a scissor-like action.

The Great Exhibition of 1851 introduced machinery from America by the two firms of McCormick and Hussey. These early reapers (see right) only cut the corn which had to be raked off the rear of the machine by hand and bound into sheaves with straw bands.

By 1880 the first twine reaper/binders came into use and developed into the horse-drawn type that were used in Woodborough in the 1920’s/30’s, with their canvas conveyor

belts and the sheaves bound and thrown off at the side which still had to be stooked by hand to dry in the wind.

The main problems were with the tension of the conveyor belts, which had to be slackened at nights to counteract the effect of the dew on them; the tying mechanism which occasionally failed or ran out of baling twine so that the odd sheaf had to be tied with a straw band, and the cutting blade which had to be re-sharpened.

The Seed Drill - Jethrow Tull, although not the inventor of the first seed drill, produced crude versions as early as 1702 and they were improved throughout the 18th and 19th centuries and as used in Woodborough in the 1920’s and 30’s. Versions were produced, not only for sowing corn, but for other seeds such as turnips.

Threshing - Threshing was originally done using a flail. In Woodborough a flail was known as a ‘leather’, because the two wooden staves were joined by a leather strap before the iron loops were introduced.

The barn at the Manor had doors opposite each other which would have allowed the wagons to pass through (see right). There were also side grooves for a threshold strip to stop the grain from being blown away. If done in the open the corn-chaff mixture was thrown across a fan, mentioned in a number of Woodborough inventories to separate the seed from the chaff.

In the first decade of the 19th century, the threshing machine was introduced and workers at the time were suffering from high unemployment. Because of a bad harvest in 1816, causing a high increase in food prices and that the threshing machine would cause further job losses, many early threshing machines were attacked and wrecked or burnt by mobs.

Threshing machines were usually hired by farmers in Woodborough in the late 19th and early 20th century. A family named Taylor owned one which was kept at Nordale on Main Street. About 1950 the first combined harvester came to the village, proved by Mannie Foster’s accounts.

Left: A common type of threshing machine powered by a steam tractor at Manor Farm 1930.

Right: In the 1950’s combined harvesters were introduced three being used near Lowdham Lane.

Note both photos are Woodborough scenes

Barley, Ale and Beer - Church ales were very common in the 15th century. Men and women sold and drank ale in the church itself or in the churchyard to raise funds for the fabric or for some other good purpose. E. M. Trevelyan in his Social History of England, states that in the reigns of Queen Anne and George I, 1702-1727, in counties such as Cambridgeshire, of all the corn grown, over 80% was barley to make malt for use in ale and beer. It was safer to drink than impure water and even the children drank ‘small beer’.

It is difficult to estimate the proportion of the varieties of corn grown in Woodborough, whether wheat, rye, oats or barley as the inventories are often vague with such terms as ‘all the corn and hay’ or ‘all the corn in the field’ but they point to the fact that a lot of barley was grown in the village, mainly for the brewing of ale and beer. It is obvious from the amount of brewing equipment and malt in the inventories that in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, Woodborough people brewed their own ale and beer.

The gentry, yeomen and husbandmen in the village had their own brew house or kiln house, even James Cliffe, who is described as a labourer had a brew house. Many inventories do not go into detail, just recording the equipment as ‘all the brewing vessels’. Those that are described by name point to the various processes involved. First the barley was steeped in water in a steep vat where it was allowed to sprout. It was then dried, having been spread over a hair cloth in either the brew house or kiln house. There are a number of records of brewing leads (leads - vessels made of lead for part of the brewing process), cisterns and steep vats, the latter having a number of other uses.

Mash vats were where the malt was then mixed with water to form wort, an infusion of malt and barley in the first stages of brewing. It was then put into a gyle vat or wort-tub in which the wort was left to ferment. We often find malt querns, pestles and mortars, various sized tubs, barrels and coal in with the brewing vessels. Most inventories contained malt which varied from one shilling to two shillings and eight pence a strike over the years. Strikes of malt were often left in Wills or listed as debts in the inventories. A strike of barley weighed about 25 lbs [pounds] varying in different parts of the country. In 1719 when it was worth two shillings a strike, Mark Hather, a rich yeoman, must have also traded as a maltster as his malt in his malt chamber was worth £75 17s 4d, equivalent to between 8½ and 10 tons.

Hops - Hops were introduced into England in the reign of Henry VIII, 1509-1547. There were church ales at this time which the church brewed and sold to the village people in aid of church funds. As church attendance was compulsory everyone was expected to be there. The great era for the growing of hops in Nottinghamshire began in the reign of George II but was chiefly in the reign of George III, 1760-1820. Most of the numerous index cards relating to hops in the Nottingham Local Studies Library have George III penciled in but as he reigned for 60 years the information covers a long period. It was a very productive time and George III did his share by having 9 sons and 6 daughters!

The greatest hop growing area in Nottinghamshire was in the Wellow, Eakring, Ollerton, Southwell and Retford regions [some 12 or more miles from Woodborough in the north and north-east of the county] where in 1790 there were a thousand acres planted with hops and in 1844 they were still being planted at Ordsall.

The variety of hops grown in Nottinghamshire was called ‘North Clay’ and although it was not as productive as the Kent hops it was stronger. As it grew best on wet or boggy land large areas of boggy scrub and waste land were cleared. In 1798 Lowe in his Treatise on the Agriculture of Nottinghamshire said there were 80 acres at Rufford, 30 at Ollerton, 30-40 at Elkesley and 75 acres at Boughton but it was reported that at Boughton it was only half of the area grown there previously.

In 1828 at Southwell land formerly used for growing flax, and there were flax pits there, was converted into a hop garden. Ash groves were planted in some areas for use as hop poles.

There is a close in Woodborough still called the Hop Yard. If you go down the village street to the Nag’s Head and instead of going left to Shelt Hill or right down Lowdham Lane, go straight on you would find yourself in the Hop Yard beyond the cottages.

The village dyke runs alongside it and it would be ideal for hop growing. A report states that there were annual Hop Fairs in Ollerton, Retford and Southwell where hops were bought and sold and no doubt much merry making took place.

Right: Woodborough’s hop yard would have

been the field to the right of the buildings.

Ollerton’s hop fair was on the last Friday in September and Retford’s on the first Saturday in November, presumably depending on when the hops were ready.

Philip Lyth, in his History of Nottinghamshire Farming, published in 1989, states that with the breweries being concentrated in the towns together with the shortage of labour for hop-picking, by 1880 the growing of hops in Nottinghamshire had ceased.

Apples and Stone Fruit - From the 1609 Sherwood Forest Map most of the properties on the north side of the village extended from the street to the back lane access to the Open Field (Moor Field). Judging from the way householders used these plots in the 1930’s the part nearest the house would be cultivated for vegetables and the rest as far as the back lane was orchard in which there would be apples, plums and damsons.

Robert Lowe in his Treatise on Nottingham Agriculture mentioned that Woodborough was noted for its stone fruit and a carrier’s cart went weekly from the village to Tuxford probably for the market there. If Lowe in 1798 mentioned the stone fruit, which was still in Woodborough orchards up to the Second World War, and 1961 it is possible that they were being grown in the 1600’s. Being fruit that would not keep they don’t appear in the inventories, but apples certainly do.

The first reference to them is in the inventory of William Sheppard in September 1603 when their value was included with his hay, and in John Clarke’s inventory of July 1662 his apples in the orchard were value at £2. By comparison his horse was valued at £2 10s.

Of course the Bramley apple, that wonderful keeper, had not been developed by Merryweather of Southwell until 1876, but there surely have been some earlier varieties that would keep in store for a short time, especially in store chambers under a thatched roof. William Pickard’s bushel of apples on 12th November 1675 were valued at 3 shillings. By Robert Lowe’s period, 1798, the apples of Robert Wheeler on 6th November 1758 in his store chamber were worth 3 shillings.

In more modern times those market gardeners and farmers with facilities for storing apples — a frost free building and perhaps available straw were able to keep apples throughout the winter and into the early spring when they would fetch a better price. In March 1947 Mannie Foster recorded selling two lots of apples for about £77 and £37 and three more lots, together with brussels sprouts for about £75 pounds — useful when other sources of income were few.

The vegetable garden at the School House on Lingwood Lane was on the west and south sides of the large playground. It had nine apple trees, a Warner’s King, a Lord Derby, a Lord Suffield and a Bramley, all cooking apples. Eating apples were a James Grieve, Pike’s Pearmain, a Blenheim Orange, an Ellison’s Orange, planted by Mr Saunders, the headmaster, and another which was never identified.

For stoned fruit there was a greengage, two ‘Johnnies’ [Roe] plum and a Victoria plum. The Johnny was an almost black-skinned plum with a bloom like a grape and a golden flesh, so full of juice that it ran down your chin if eaten raw. Most of the village people with orchards either took or sent their plums and damsons to market in late August and early September.

Bees and Honey - Beehives are mentioned in 14 inventories between 1578 and 1742 but far more households would have kept bees in the old straw skeps (see below right) before 1800. Honey was the main sweetener in England until the 18th century and was also an important ingredient in baking. Its anti-bacterial properties were well known so that it was useful in treating injuries and could also be made into mead. Honey is also an excellent source of energy. The beeswax could have been used for polishing what little furniture they had and also for candles.

The first record of bees in the Woodborough inventories is the 12 hives belonging to George Clarke in 1578 valued at £1 10s. Nathaniel Foster, Gent, 1669, of the Old Manor or Nether Hall, had seven hives worth £1 15s whilst John Thorpe, 1730, had six hives worth 3s 4d each.

Many of the bee keepers were named Lee or Cliffe so perhaps bee-keeping was traditional in certain families. In many of the inventories the number of hives is not given, just the value is stated. The first mention of sugar in Woodborough inventories is in that of Charles Lacock, 1684, who had three casters and a sugar dish and spoon.

As he was one of the gentry he would have been able to afford sugar, which was expensive.

The inventory and Will of Henry Alvie, 1616, had three hives of bees valued at 15 shillings. He must have considered them valuable because in his long and detailed Will, he wrote the following:-

I give to my daughter-in-law Grace Alvie one hive of bees which she will choose.

I give to the eldest daughter Elizabeth one hive of bees which she will choose when Grace hath chosen.

I give to my second daughter Jane one hive of bees which she will choose when the said Grace and Elizabeth hath chosen.

Perhaps when he made his Will on 2nd December 1615 he thought there were four or more

hives. He was buried on 16th February 1616 but by the time his appraisers wrote the inventory on 29th March they could only account for three.

Market Gardening - Now to the other side of agriculture in Woodborough — market gardening. When Nottingham had its Enclosure award in 1845 and began to expand beyond the old city boundary, the population increased with the subsequent need for more food. There were often periods of short time working in the framework industry and the Woodborough Male Friendly Society, which was dominated by frameworks knitters, in its wisdom, purchased 16 acres of land in the village in 1856 which it divided into twelfths of an acre, 400 square yards, and eighths, 600 square yards. It was intended that members would be able to grown sufficient crops, potatoes and vegetables, etc. to sustain the family and a pig. In 1894 the Society purchased another 8 acres known as the New Lands which was divided into fifths of an acre, 900 square yards, so that some members had quite sizeable plots and one presumes gained a lot of agricultural know-how.

According to Frank Small, strawberries were introduced into Woodborough about 1880 and became a profitable side-line for the framework knitter allotment holders. Obviously by the 1901 Census, many former framework knitters had decided that market gardening was a more profitable occupation as there were 20 men listed as either market gardeners working for themselves or as market gardeners employing additional workers. Two more classed themselves as framework knitters/market gardeners and there was also a carrier/market gardener. Clearly by 1901 the Nottingham greengrocers were being well supplied from Woodborough market gardeners.

By the 1930’s, with the last of the frame workers at Desborough’s factory on Shelt Hill facing unemployment, some new recruits such as Frank Small and Sam Middup turned also to market gardening and there were still up to 20 market gardeners in the village. Also with the demand for vegetables in Nottingham, some of the more traditional farmers, such as Fosters at The Manor and Hallam’s at Home Farm, were growing sizeable quantities of cabbages, cauliflowers and brussels sprouts and small amounts of strawberries and beetroot.

Right: George & Harry Baggaley horse hoeing on

the Hawley Fields near Old Manor Farm in 1950.

Woodborough scene.

What sort of produce did Woodborough market gardeners/farmers take to market? Fortunately Mannie Foster kept detailed weekly accounts, not only for the market garden produce, but also for the general expenses at The Manor. From the period 1944-1952 the main kinds of produce month by month were as follows:

January — sprouts and brussels tops

February — sprouts, tops and apples

March — sprouts tops, Savoys [cabbages] and apples

April — brussels, rhubarb and apples

May — cabbages, rhubarb, purple sprouting

June — cabbages and broccoli

July — cabbages, lettuce, peas and beetroot

August — cauliflower, beetroot, peas and kidney beans

September — cauliflowers, cabbages, peas, kidney beans, beetroot, plums, damsons

October — cauliflowers, beans, damsons, plums and early sprouts

November — cauliflowers and sprouts

December — cauliflowers, sprouts and tops

In addition The Manor grew strawberries on the Leys field. No doubt many market gardeners would have taken new and main crop potatoes to market but The Manor usually sold theirs to wholesalers. Stored apples and potatoes would fetch good prices in the early months of the year — there were no supermarkets importing out of season fruit and vegetables at that time. During and immediately after World War II, The Manor was getting a Ministry of Food subsidy for growing large quantities of potatoes.

Potatoes and Sugar Beet - Potatoes - What would we do without the humble potato? And yet if you had lived in Woodborough up until about 1800 you would probably have never grown one or even seen one. In all the Woodborough Inventories, with their detailed information on crops grown, crops in store in outhouses and barns, and in the store chambers in their houses from 1567 until the last two detailed Inventories of 1758 and 1759 there is not a single mention of the potato.

But less than a century later, by the early and middle 1800’s the growing of potatoes was common in all levels of society. So popular was the potato that the reliance on it as a staple food to feed the rapidly increasing population in Ireland, when hit by potato blight, led to the famines and starvation of the Irish in 1845 and again in 1878-80.

The arrival of the potato must have come as a blessing to those in Woodborough hit by the Inclosure, who found they couldn’t afford to drain and fence their allocation of land and had to sell it. Now, as labourers and farm workers and unable to grown their own barley etc. they would be able to grow potatoes on the land adjoining their cottages which would not only be a source of food for themselves but with vegetable and other household food waste would still be able to keep a pig.

Although in the 1930’s there were few Woodborough farmers growing large acreages of potatoes. But together with the large number of market gardeners in the village at that time, both the local population and the Nottingham Wholesale Market would have been adequately supplied. Most people in the village with a vegetable plot grew their own and many used a clamp to store them.

Apart from the laborious, but extremely satisfying lifting of potatoes by hand, there were two main ways of lifting potatoes using horses. One was using an angled share, rather like a large plough share but instead of a mouldboard it had inclined tines. The share lifted out the soil and potatoes and as the potatoes slid up the tines, most of the soil would drop out. Mannie Foster’s accounts have revealed the following:

- August 1947 cheque for potatoes sold £71 4s 4d

- April 1950 sold potatoes £90

- May 1950 sold potatoes £130 19s

- May 1951 sold potatoes to Tooleys (wholesalers) £157

potato harvest as the following entries in the Woodborough school logbook testify:

- 1941 October 30 - school closed two days for potato picking.

- 1943 October 25 - four scholars potato picking at Gunthorpe.

- 1945 October 22 - Upper Standard scholars have completed their period of potato picking and given every satisfaction. Their employers paid them 9d an hour instead of the standard price of 6d.

Sugar Beet - Honey was the main sweetener until the 18th century when it was giving way to sugar. The conical sugar loaves or replicas of them can be seen in museums. The larger loaves used in the kitchens of the gentry weighed up to 13 lbs (pounds) in weight.

During George III’s long reign, 1760-1820, luxuries like tea and sugar, the latter now in refined white loaves, became more common. Miss Marriott, who had the shop, circa 1930, next door to the Institute, would weigh up the sugar from a sack or box into the ubiquitous blue paper bags.

So why did the growing of sugar beet occur in Woodborough although on a somewhat limited scale when compared with the amounts grown in the alluvial Trent Valley and the vast expanses of East Anglia? After World War I it was recognised that we must grow sugar beet as we could no longer rely on supplies of cane sugar from overseas due to the vulnerability of ships crossing the Atlantic. The early 20th century saw an enormous increase in the production of sugar beet in East Anglia and the first factory had been built there in 1912. Enormous amounts of sugar beets were being taken by rail in the 1920’s/30’s to the sugar beet factory at Cantley between Norwich and Lowestoft.

Now to Nottinghamshire. At Kelham in 1917 a sum of £170,000 was spent by the Ministry of Agriculture and Home Grown Sugar Limited to purchase land in the area to grow sugar beet as an experimental crop and the first factory was built at Kelham in 1921. The Anglo-Scottish Beet Sugar Corporation then built a factory at Colwick in 1924. Samples of beet from the Manor would be tested for soil weight and sugar content before the load was emptied into an enormous flume. In 1972 when the Kelham factory closed for the season it had produced 30,000 tons of sugar from 250,000 tons of beet with the sugar content in 1970/71 about 16½-17% and 26 Irish labourers then returned to Ireland. According to Philip Lyth, 7,800 acres of sugar beet were grown in Nottinghamshire in 1939 but by the end of the war the acreage had more than doubled to 17,500 acres.

After 1950 more sophisticated potato and sugar beet lifters were devised to separate the haulms in the case of potatoes and an elevator to load them onto a side trailer, and in the case of sugar beet a topping knife removed the tops from the beet before they were lifted and then elevated onto the side trailer. This superseded the hand-cutting of tops and the loading of beet by hand onto carts or trailers.

Child Labour in the 1930’s/40’s – plant setting and strawberry getting and tenting - In order to grow the vast quantities of cauliflowers and cabbages the Woodborough farmers and market gardeners took to Nottingham (Mannie Foster packing 60 dozen on the lorry) the young seedlings and plants were grown in seed beds at the farmstead or market garden until they reached about 8 to 9 inches tall. They were then lifted, put into skeps and taken to the area to be planted where the soil had been harrowed and rolled to create a fine tilth.

Planting was all done by hand, usually after school until it was dusk, the man making a slit in the soil using a spade, the boy dropping the plant in the slit and the man firming it in with his foot. For this the boys would be paid about 1½d to 2d an hour, back breaking work and often the boys school work suffered as a result on the following day.

In the school log book for July 3rd 1928 the entry is “I find several scholars are not fit to do their usual school lessons. They are often setting plants until 9 p.m. and are gathering strawberries during the early hours of the morning”. Another job the boys had was ‘tenting’ i.e. scaring the birds away from the strawberries night and morning. Other entries from the school logbook reveal:

- November 3rd 1916 several of the Upper Standard boys have been absent this week potato picking.

- September 19th 1917 school closed for a week to enable the scholars to help with the potato harvest and in 1918 the same thing was written for September 27th.

The strong Woodborough land appears good for growing cereals, especially wheat. During the summer of 2010 one only had to look towards Park Farm and Spindle Lane from Potter’s Drive at the top of Bank Hill, or from Hungerhill Lane towards Bank Hill to see the amount of wheat being grown in the Woodborough area. For some reason the Manor, according to Mannie Foster’s notes, traded its corn with Newark Egg Packers. In 1950 and 1951 they received cheques for wheat for £119, £275, £208 and £164 and purchased barley seed from them in May 1951 for £46 16s.

Transport - How was this produce taken to market? The farmers took their own produce by horse and cart and later by lorry to the Wholesale Market in Sneinton where the various greengrocers would come and choose the items they needed for their shops. Those without transport, pre-1925, had their produce taken to Nottingham by the carriers, North, Dunthorne and Leafe. Mr Leafe had two carrier’s carts, one pulled by a single horse and a two-horse cart. The produce was either taken to the greengrocers or to the Central Market between Glasshouse Street and Huntingdon Street near the centre of Nottingham, built in 1928 when the market in the Old Market Square finally closed. Some Woodborough market gardeners had stalls which they rented on Wednesdays and Saturdays in the Central Market, people such as Mannie Foster’s aunt Kate from the Old Post Office and the Bradley family who lived opposite what is now Cottage Farm, at one time the Old Cock & Falcon Inn.

After 1925 when Barton’s Buses started to run from Woodborough to Nottingham, it is said that when the bus passed Mr Leafe’s carrier’s cart, those on board the bus, who used Mr Leafe to take their produce to market would duck down in case Mr Leafe saw them and might in future refuse to carry their goods. Some of the market gardeners had a horse, e.g. Mr Arthur Snodin and Mr Edwin Spencer, the latter’s horse was killed by a stray bomb in the fields against Ploughman Wood during World War II. On occasions a horse was shared or borrowed, but after 1945 the little grey Ferguson tractors came on the scene and were readily adapted by the more go-ahead market gardeners. In the days before 1961 when the village started to expand, many people had an orchard with stone fruit e.g. plums and damsons, as well as varieties of apples which would be sent or taken to market. Robert Lowe, in his 1798 Treatise on Agriculture in Nottinghamshire mentioned Woodborough being noted for its stoned fruit. After 1961, as the older market gardeners retired and orchards were sold off for building plots, market gardening in the village gradually declined.

A later addition was a revolving cage after the share to riddle out the earth. Early horse-drawn potato spinners had a rotating wheel (40) to which were attached a number of hanging metal tines. Already in use by 1875 it removed the potatoes from the soil too quickly, damaging the skins, rendering them useless for storing in clamps. By 1910 the spinning type (see illustration right) had been improved and was in general use, although the elevator lifting type was still used.

The two World Wars and Dig for Victory campaigns saw an enormous increase in the growing of potatoes in gardens, and the need on farms for extra hands to harvest them. Schoolchildren were given time off school to help with the

Left: Leafe’s lorry on Main Street 1931. Right: Hallam’s of Hall Farm 1945.

Both photos are Woodborough scenes.

The Effect of two World Wars in Woodborough - Earlier events that had a great effect on Woodborough’s agriculture were the end of the feudal system, the Woodborough Inclosure Award, the Nottingham Inclosure Award of 1835, which opened up Mapperley Plains and the Nottingham markets, and the decline of our village’s framework knitting industry.

The two World Wars also had their effects; one was the ploughing up of permanent pasture to arable in order to grow more food. The Big Faley (Far Ley) was ploughed up from grassland in World War I, and owing to the steepness of the slope and the heavy clay soil a multi-furrow plough worked by cable from stationary steam engines was used (see below left). By the time the permanent pastures of the Cockleshell and the Bracken field (wind pump), with all their wild flowers, corncrakes and grey partridges were ploughed during the Second World War, tractors had appeared on the scene.

|

Wood Farm. |

Woodborough Park Farm. |

Stoup Hill Farm. |

Bank Farm. |

|

Below other farms in the Woodborough Parish. |

|||

|

Moor Farm. |

Grimesmoor Farm. |

Shelt Hill Farm. |

Wood Barn Farm. |

Drying harvested hemp.

Harvesting hemp.

Flax stems being pulled.

O.S. Map revised in 1993, shows the positions of most of the Woodborough farms, the

exception being Stoup Hill farm which is to the west of Woodborough Park or Park Farm.

Below four farms that lie to the west of Woodborough in the Woodborough Valley.

The shire horses, used for a source of power for almost all agricultural purposes/implements in Woodborough until the middle or late 1930’s were replaced by the Fordson tractor and later by the little grey Ferguson with it hydraulic take-off (see above right), a boon to smallholders and farmers alike.

The Middle Manor had at least four working horses for two plough teams which, when not needed for ploughing, were used for general work. The tractors, together with the combine harvester, reduced the number of farm workers needed. Whereas a good ploughman might plough an acre a day with a pair of horses, this could be multiplied many times by a tractor pulling a multi-furrow plough. When the cutting of the corn with a horse-drawn binder, the stooking of the sheaves and carting and stacking of the corn would involve many workers for several days, not to mention the thrashing of the corn, a combine harvester needed just one man and a tractor driver for all these operations. It is interesting to see in Mannie Foster’s account that the Ministry of Food, during and immediately after World War II, paid for work done by Land Girls and prisoners-of-war.

To sum up - The major influences on Woodborough’s agriculture would have been the Black Death (circa 1348); the plagues in the 17th century; the Enclosure of Woodborough in 1795, with the improvement in farming techniques; the Industrial Revolution with the improvements in horse-drawn machinery; the demise of the framework knitting industry leading to the surge in market gardening; the First World War with its emphasis on home-grown produce; the Second World War with the use of the tractor and its ancillary equipment and the introduction of the combine harvester.

ooOOoo

Acknowledgement:

- From a talk researched and given by Peter Saunders to

Woodborough Local History Group in 2010.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

|

|

|

Links to paragraphs :- |

|

|