Woodborough’s Heritage

An ancient Sherwood Forest village, recorded in Domesday

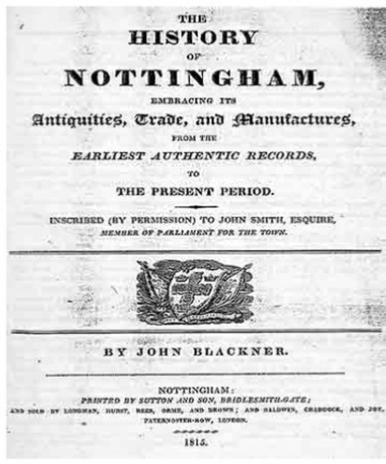

Framework-Knitting Branch by John Blackner

Indeed, so much is this town [Nottingham] dependent upon the engine, known by the name of the stocking frame, and its appendant machines, that, if it stood still, all of the businesses must stand still also. The town may in fact be compared to one vast engine, whose every part is kept in motion by this masterpiece in the mechanic arts.

The inventor of this curious and complicated piece of machinery, which, in many instances, consists of more than six thousand parts, was one William Lee, M.A. of St John’s College, Cambridge, and was heir to a small freehold estate in Woodborough, the place of his nativity, which lies about seven miles from Nottingham. Mr Lee being deeply smitten with the charms of a captivating young woman of this village, he paid his addresses to her in an honourable way; but, whenever he waited upon her she seemed much more intent upon knitting stockings and instructing pupils in the art thereof, than upon the caresses and assiduities of her suitor: he therefore determined, if possible, to mar the prospect of her knitting, under an idea, no doubt, of thereby inducing her to change that for one more congenial with his views. The former part of his project Mr Lee accomplished in the year 1589, by the invention of an engine or frame for the knitting of stockings, which possesses six times the speed of the original mode, and which has admitted of an almost endless variety of substantial and fancy articles being wrought upon it.

After the accomplishment of so great an undertaking, it seems other notions than those of gaining the fair and fickle object of his former pursuit attached themselves to the mind of Mr Lee, ambitious of being

The following article is reprinted in full from: The History of Nottingham embracing its Antiquities, Trade, and Manufacturers published 1815 - Framework-knitting Branch (Pages 213 to 219 inclusive)

the inventor of so useful a machine, he immediately adopted measures which appeared to him the most likely to secure wealth and future fame. ¹

Note ¹: Tradition informs us, that the first frame was almost wholly made of wood − that it was a twelve gauge − that there were no lead sinkers: and that the needles were stuck in bits of wood. We are likewise told, that the difficulty Lee met with in the formation of the stitch for want of needle eyes, had nearly prevented the accomplishment of his object, which difficulty was at length removed by his forming eyes to his needles with a three-square file. We have information too, handed in direct succession from father to son, that it was not till late in the seventeenth century than one man could manage the working of a frame: the man who was considered the workman, employed a labourer who stood behind the frame to work the slur and pressing motions; but the application of treadles and of the feet, rendered the labourer unnecessary.

The known partiality of Queen Elizabeth for knitted silk stockings, which she had worn since the year 1560, would naturally induce Mr Lee to think that the production of an article so superior in quality, and wrought with such superior facility, could not fail to procure the royal patronage as a reward for his invention: an idea which every speculative genius is justified in fostering; but which many have fostered in vain. Flushed with this honourable expectation, Mr Lee hastened to London, presented his frame to the Queen, and worked in it in her presence. But, whether she was too much engaged in enjoying her triumph over the Spanish Armada, or in dalliance with, and in cajoling her different admirers, cannot now be determined; this, however is certain − she treated Mr Lee and his invention with neglect, if not with contempt. Stung with the ingratitude of his sovereign, and meeting with no better treatment from his countrymen in general, he therefore sought encouragement at Roan [Rouen] in Normandy, under the protection of the celebrated Henry the Fourth of France. Here, with nine frames and so many workmen that accompanied his fortunes, he met with the encouragement of an enlightened monarch and an applauding nation; but misfortune, the usual attendant on merit, was determined to haunt him through all his earthly pursuits. The stroke of an assassin, which brought the good King Henry to the grave, made way for the mis-rule of Louis the Thirteenth, whose bigotry and persecution swallowed up every virtue which beamed in the court of Henry, and, consequently, every encouragement which the latter had given to mechanic arts. Mr Lee, finding himself neglected at Roan, applied at the foot of the royal fountain in Paris; but the streams of that fountain were stopped when merit applied for aid; therefore he met nothing in his application but disappointment and chagrin. Finding his merits thus neglected both at home and abroad, he gave up his mind to the empire of grief, which soon gave him rest from his sufferings in the grave. Seven of his workmen, with their frames, returned to England, leaving two behind at Roan with theirs. Thus England owes the return of this useful art, to the hand of an assassin and the ignorance of the French king, after her ingratitude had driven it away.

One Aston, of Thoroton in this county [Nottinghamshire] having been taught the art of framework-knitting by Mr Lee, before the latter left this country, and being a person of considerable genius, had retained a tolerably correct knowledge of the frame, notwithstanding he had followed the business of a miller during the time his fellow workmen had been in France; and, still having a desire to further the invention, he joined the workmen on their return; and they, in conjunction, soon restored the disorganized frames to a working state. But whether they carried on the business in Nottingham, or in what other part of the county thereof, is uncertain: probably, after they had brought the frames to a tolerable state of perfection, they sought different directions, according to their several inclinations and views. It appears certain however, from the information handed to us by Deering, that there were but two stocking frames in Nottingham in 1641; nor was the increase very great during the next hundred years, as appears from the following state of the trade in 1939:−

Framework-knitters - 14

Frame-smiths - 12

Needle makers - 8

Setters-up - 5

Sinker makers 50

At this period we find none ranked in the profession of a hosier; consequently we have a right to conclude that the business of a hosier had not then assumed a distinct shape; and also that every framework-knitters disposed of his own goods in the best manner he could. This will account for the slowness of the progress made by the trade during the period alluded to; for it is very unlikely that any serious number of workmen would be able to furnish themselves with frames to work in, and then have to depend upon the precariousness of a sale for subsistence for their families.

For a considerable time after the revival of this important art in England, its principal nursery was London, which was partly occasioned by a want of country hosiers, and partly by the rage in those days for what was called fashion work: the custom then being to wear stockings of the same colour as the other outward garments, which caused a continual demand for small and immediate orders. But when this custom declined, and country hosiers began to exert themselves, the London dealers found their account in depending upon the country manufacturers for supplies. Hence it is that, within the last sixty years, the manufacturing of stockings in London has been on the decline, while those places more congenial to the interests of the trade, it has been more rapidly on the increase. So that, at the present time, a few fancy frames and those used as decoy ducks in retail shops, are nearly all which the metropolis can boast of.

Shortly after the return of Mr Lee’s workmen from France, the Venetian ambassador in London engaged one Henry Mead, for five hundred pounds to go to Venice and take a frame with him, for the purpose of establishing a framework-knitting art in that country; but it appears that Mead had not merit equal to the expectations of his employer, for the project failed for want of mechanics to keep the frame in a working state; in consequence of which it was sent back to England for sale, along with some wretched Venetian imitations. An attempt was also made by one Abraham Jones to carry the invention to Holland; and, the ingenuity of the adventurer, in all probability, would have enabled him to carry his scheme into execution, and not the plague, which then raged with violence in the Low Countries, hurried him and his connections to the grave. His frame was afterwards sent to London for sale.

In the hope of preventing a recurrence of these dangers to the country’s interests, in this now much – sought-after business, and likewise to guarantee it against the mischief arising from persons being engaged in it that had not served an apprenticeship to the trade, and thereby, for the want of experience, introducing badly wrought articles into the market, to the manifest discredit of the rest, the framework-knitters in London petitioned Oliver Cromwell, as protector of the commonwealth of England, to grant them a charter and to constitute them a legal company. This petition was complied with, but, whether the granted instrument was thought insufficient, in its regulating and guaranteeing powers, or whether the company thus constituted, thought a charter from Cromwell improper to be acted upon after the restoration, we are not informed; be this however as is may, the company petitioned Charles the Second, soon after he obtained the diadem, for a constituting charter, which was granted them in 1664, and which incorporated them under the name of “The Worshipful Company of Framework-knitters;” to the governed by a master, wardens, and assistants, who are directed to be chosen annually on 24th June. These officers had powers vested in them by virtue of the charter, to make by-laws from time to time for the government of the trade, as, in their estimation, its interests might require; which by-laws, if signed by the Lord Chancellor, the Lord Chief Justice of the court of Kings Bench, and the Chief Justice of the court of Common Pleas, are valid in point of law, if not in direct opposition to the statute law of the land, or when they run counter to the interests of the country; the latter question being left to the decision of a jury. ²

Note ²: It is the duty of these great law officers to give notice to chartered companies, if an act of parliament be in agitation inimical to their interests. Deering says that Cromwell refused to grant a charter to the framework-knitters; but here our antiquary is mistaken, for I have a printed document by me which proves to the contrary.

The body of by-laws now in existence was framed in 1745, and was signed by Philip, Lord Harwick, Lord Chancellor, by Sir William Lee, Knight, Lord Chief Justice, and Sir John Willes, Knight, Chief Justice of the Common Pleas.

Deering, when speaking of the framework-knitters’ company, has the following remarks:− “In process of time, when the trade spread further into the country, they also in proportion stretched their authority, and established commissioners in the several principal towns in the country where this trade was exercised; there they held courts at which they obliged the country framework-knitters to bind and make free, &c. whereby they for many years drew great sums of money, till some person of more spirit than others in Nottingham brought their authority in question, and a trial ensuing, the company was cast, since which time the stocking manufacture has continued entirely open in this country”.

The want of a date, and the disingenuous manner in which the above paragraph is written, have left the readers’ mind in doubt, as to the nature and consequences of that trial, particularly when he considers the subsequent conduct of the company. It would be fair however to conclude, from our author’s statement, that no circumstance had taken place from the time of the trial to that in which he wrote, by which the validity of the charter had been ascertained. But, by recurring to recorded facts the truth will best appear. In an old printed document, referred to in the last note, entitled, “Case of the Framework-knitters”, we find the following:− “Some short time before the year 1734, a dispute arose between the members of the company in London and some manufacturers in Nottingham, which occasioned a law suit; but the merits of the question in that suit were not fully tried; the company being non-suited for want of legal form in the by-laws produced at the trial, which appeared to be confirmed by the Chancellor and Judges, but could not be proved to be the act of the company, which was the reason the court did not try the merits. The result of this dispute was, that the artists in the country were for having the by-laws amended, and till that was done, would not comply therewith; not could the company get any deputies to act for them in the country”.

Here then we see that the merits of the charter were not tried; and that it was the incongruity of the by-laws, which brought on the dispute. Notwithstanding this however, as a new code of by-laws was not formed till 1745, it is no wonder if so long a lapse of time brought the charter into disuse in the country; though the sanction of those by-laws by the three greatest law authorities in the nation, about twelve years after the trial, proves that the validity of the charter was then considered as unshaken.

We are now arrived at a period in the history of these affairs in which the company and the trade at large may be considered in different points of view − the company may be compared to a man in the decline of life that principally depends upon the toil of others for support, and whose every effort serves to betray his own weakness; while the trade may be likened to a blooming youth that has just learnt the value of his own strengths, and who considers every farthing drawn from his toil, under pretence of supporting him, as an unjust tax upon his industry. The company now endeavoured to enforce payment from the country workmen, finding that persuasion and low cunning had lost their effect; and the trade threatened them with annihilation if they persevered. In 1751, the company commenced actions against two workmen at Godalming for not paying their quarterage; and the trade threatened, if they proceeded in the actions, to apply to parliament for an act to unshackle it from the company’s trammels and break up their body − the company took the hint, and let the matter drop; and the trade found its advantage in their imbecility.

Various attempts have been made since that time to restore to the charter its pristine authority, under the idea of stopping colts³ from working at the business, who, it is contended, have been the cause of many goods being introduced into the market of an inferior quality, from their not possessing a competent knowledge of the art. Without entering into the merits of this question, which in truth do not belong to history, the reader may rest assured that the charter as far as respects the prosperity of the trade, is forever laid to rest.

Note ³: A name given to persons that work at the business who have not served a regular apprenticeship to it.

In 1805, a most extensive association was formed among the framework-knitters of Nottingham, Derby, and Leicester, and their respective counties, where the business is principally carried on, for the purpose of raising money to enable the company to prosecute a man of the name of Payne, of Burbage, in Leicestershire, for following the business and learning others without his having served an apprenticeship, on the issue of which prosecution the future prospects of thousands, similarly circumstanced, depended. Payne was supported by the Leicester and Leicestershire hosiers, who being the principal manufacturers of coarse and inferior goods, felt themselves peculiarly interested in pushing the trade among those workmen that, from their little knowledge of the art, were the least likely to content for regular prices, and for properly fashioning goods. After a world of litigation and expense on both sides, the matter was brought to a final hearing in Westminster-hall, in February, 1809, when, though the charter was admitted to be as good in law as other charters of a like description, it was forbidden to be put in force, any further than as relates to the internal government of the company, such as choosing masters, wardens, &c.; and for the purpose of spending the money which the members of the company may think well to contribute; providing such money is not applied to purposes contrary to the statute law of the land.*

Note* As a proof of the folly of working men being persuaded by attorneys to expend their money on such occasion, I will relate the following circumstances:- Being in London on some public business, along with Mr German Waterfall, shortly after the above question was decided, we called on Mr Laudington, the company’s solicitor, to make some enquiries about the business, when he complimented the people of Nottingham for their superior penetration and understanding, in consequence of their backwardness in paying contributions in supporting the company on this occasion, because, considering the altered state of trade from the time the charter was granted, the cause was hopeless; notwithstanding this very man had used his influence to persuade them to contribute while the trial was pending, from an opinion given on his part that they would be ultimately successful. Mr Laudington received about £300!!

As a proof that the legislature has brought the framework-knitting business of some importance in its own abstract merits, we have only to mention the act passed in the 7th and 8th of William and Mary, which inflicts a penalty of forty pounds, with the loss of frame, upon any person caught in the act of sending one to a foreign country. In 1766, an act, commonly called the Tewkesbury act, was passed, the object of which was to prevent the fraudulent marking of framework-knitted goods; a practice having been long persuaded by some hosiers of ordering their workmen to mark the goods with more oilet-holes than corresponded with the number of threads in the material of which such goods were made, except those wrought of silk; and except such goods were wrought of a material of less than three threads. But the salutary provisions of this act are now rendered nugatory by flaxen stockings being nearly disused, and by the invention of machinery to spin cotton and worsted yarn, which, generally speaking, renders more than two threads unnecessary. In the 28th [year] of his present majesty, an act was passed which constituted it felony to break or wilfully injure a stocking frame; and it likewise directs that the holder of a frame shall give it up to the owner after he has received from the latter “the customary and usual notice”; which customary and usual notice, from long established practice, consists of fourteen days. In consequence of the crime of frame-breaking being so extensively pursued in 1811, an act was passed which made it death to break or wilfully injure a stocking or lace frame, or the machines thereunto appended; but this was shortly superseded by another, which placed stocking, lace, and other frames under one common protection, and reduced the crime of breaking them to the punishment of transportation, according to the act of the 28th of the king.

It is unnecessary to enter into a particular description of the various and numerous parts which constitute a stocking frame, since it is not like those productions of fancy, whose existence may be measured by a month, and a description of whose components parts might gratify idle curiosity during an hour. No, the frame is the offspring of profound genius and nice discrimination has been brought to its present high state of perfection by the united talents of many; and this become a staple article in the complex system of our national manufactories, as well as a great supporter of our prosperity and fame; nor will it ever be laid aside so long as stockings, and a great variety of other articles of dress, are considered necessary to the customs of society. But with respect to a description of the various additions to the stocking frame, the case is otherwise, some of which are nearly forgotten, and other may share the same fate; therefore of them a more particular description should be given. Deering states, that, in his time, no essential article has been added to the original machine; the last sixty years, however, have made ample amends for the lack of early invention. And, it is worthy of remark that almost every improvement which this complicated piece of workmanship has received, has owed its birth to the genius of Nottingham or its neighbourhood. To be able to do justice to the memory of everyone that has made discoveries or applied them to the stocking frame, would be highly gratifying; but this is impossible, since almost every invention has had several claimants. Where the claim stands supported, however, by fair testimony, the name of the inventor shall be duly honoured.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

| Navigate this site |

| 001 Timeline |

| 100 - 114 St Swithuns Church - Index |

| 115 - 121 Churchyard & Cemetery - Index |

| 122 - 128 Methodist Church - Index |

| 129 - 131 Baptist Chapel - Index |

| 132 - 132.4 Institute - Index |

| 129 - A History of the Chapel |

| 130 - Baptist Chapel School (Lilly's School) |

| 131 - Baptist Chapel internment |

| 132 - The Institute from 1826 |

| 132.1 Institute Minutes |

| 132.2 Iinstitute Deeds 1895 |

| 132.3 Institute Deeds 1950 |

| 132.4 Institute letters and bills |

| 134 - 138 Woodborough Hall - Index |

| 139 - 142 The Manor House Index |

| 143 - Nether Hall |

| 139 - Middle Manor from 1066 |

| 140 - The Wood Family |

| 141 - Manor Farm & Stables |

| 142 - Robert Howett & Mundens Hall |

| 200 - Buckland by Peter Saunders |

| 201 - Buckland - Introduction & Obituary |

| 202 - Buckland Title & Preface |

| 203 - Buckland Chapter List & Summaries of Content |

| 224 - 19th Century Woodborough |

| 225 - Community Study 1967 |

| 226 - Community Study 1974 |

| 227 - Community Study 1990 |

| 400 - 402 Drains & Dykes - Index |

| 403 - 412 Flooding - Index |

| 413 - 420 Woodlands - Index |

| 421 - 437 Enclosure 1795 - Index |

| 440 - 451 Land Misc - Index |

| 400 - Introduction |

| 401 - Woodborough Dykes at Enclosure 1795 |

| 402 - A Study of Land Drainage & Farming Practices |

| People A to H 600+ |

| People L to W 629 |

| 640 - Sundry deaths |

| 650 - Bish Family |

| 651 - Ward Family |

| 652 - Alveys of Woodborough |

| 653 - Alvey marriages |

| 654 - Alvey Burials |

| 800 - Footpaths Introduction |

| 801 - Lapwing Trail |

| 802 - WI Trail |