Woodborough’s Heritage

Woodborough, a Sherwood Forest Village, recorded in Domesday

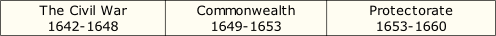

This period saw a considerable deterioration in the Parish Registers. Because preachers, often semi-literate and un ordained, were appointed to parishes in the place of the former clergy, and the Registers were given to laymen registrars, we find that from 1644 until as late as 1668 the Woodborough Registers are poorly written, incomplete, and with atrocious punctuation and spelling. Because of the non-payment of salaries there were a number of different preachers during the period and gaps in between them, which did not help the accuracy and continuity of the Registers.

There are no marriage entries between January 1644/5 and 16th July 1655, more than a ten year gap. There are two later insertions of marriages referring to 1651 and 1653 both of these relating to marriages of Mr Nathanial Foster to Sarah Scrimshaw and Martha Baker. As Nathanial of the Nether Hall was one of the village gentry he obviously had enough influence to have his or their marriages inserted at a later date.

Although the Barebones Parliament, which only lasted for five months, had imposed what was known as the Fourpenny Bribe to prevent baptisms being performed or registered, the entries for baptisms in Woodborough are fairly good, although in a number of cases the entry reads ‘was borne’ as opposed to ‘was baptised’.

Recusants (17th County Records): A recusant (especially a Roman Catholic) was a person who refused to attend the Church of England when it was legally compulsory a dissenter. In Woodborough the following were presented as Popish Recusants during the reigns of James I and Charles I, 1603-1649.

Lady Bould – spinster, Christopher Clarke Senior, husbandman, Christopher Clarke Junior, a Yeoman; Margaret Clarke, Richard Low and his wife; and Michael Lees and his wife.

In the period 1637-1840 several people were interred as opposed to buried, presumably Recusants, either Roman Catholics or dissenters. (Francis Leek, in the Prebend’s account of 1676 said that in Woodborough there were no Popish Recusants but eight Dissenters).

Population: There are several recognised methods of obtaining the population from information supplied by the Parish Registers.

The Reverend W.E. Buckland chose the one provided by the number of burials (deaths) per year over a 10-year average. His estimate was that in the years from 1591-1700 the population of Woodborough was about 280. He says that by 1800 the population of the village was about 430, but a Woodborough population table at the Nottinghamshire Archives gives a figure of 527.

The population grew rapidly from 1800 and by 1871 had reached a peak of 898, an increase of about 50 each decade during the 70-year period. There are various reasons for the increase. Perhaps the Enclosure Award increased food production from its former inefficient Open Field farming and also there was an increase in the hand framework knitting numbers operating in the village.

From 1881 there was a steady decline in the population as hand knitting was overtaken by factory production and by 1931 it had dropped to 661, an average decline of 45 a decade over the 50-year period.

Size of the village: Of course, in most of the period from 1538 to 1750, before the Enclosure Award, the village was very confined in extent, the Upper Hall being the western end with no properties on Bank Hill or Calverton Lane, no properties up Roe Lane and in Lingwood Lane beyond the church, only the school, built in 1736.

The Old Manor, where Old Manor Close now is, was the eastern end of the village with no properties beyond it and none on Shelt Hill (Dark Lane). If you take an average of a minimum of 4 as a family, with a population varying between 240 and 280, there would only be about 60 to 70 families, and the same number of properties.

Mobility of the population: Even before the Enclosure of 1795 when the trackways round the village were often in a shocking condition, there was some movement of the population. Travelling was restricted to going on foot or on horseback. There is naturally little evidence of this in the baptism records, although Thomas Martin in April 1576 ‘for lacke of a prieste he was baptised at Lambley’. It was local people who had their children baptised in the village but in the marriages, marriage licences (and burials) we find husbands, and it was usually husbands, coming from Warsop 1609, Flawborough and Clipstone 1624, Aslockton 1663, Coddington 1668, Cotgrave and Whatton 1678, Codnor 1687, Scarrington 1693, Greasley 1712, and Scriveton 1745, so obviously in spite of difficulty people managed to get around.

People who didn’t live in the village were occasionally buried here; perhaps relatives of inhabitants, or former inhabitants, wishing to be buried in or near the family grave. There are examples from Lambley 1622, Edingley 1701, Nottingham parishes in 1701 and 1721 and Epperstone 1724.

Some movement of people through the area is shown by the following entries of burials:-

- Elizabeth Dison, the daughter of John Dison, a travelling man, April 1600.

- Richard Rayneburrowe – a poor traveller, November 1611.

- Gabriell Cliff of Ruddington – slain with an axe, October 1621.

- A traveller (no name), February 1727/8.

- There is also a baptism - Sarah, daughter of Christopher Mackdonald – traveller, March 1757.

These so called Travellers may well have been returning to their place of ‘settlement’, perhaps they were ill, disabled, or couldn’t find employment in the town or village where they had been living.

Settlement: ‘Settlement’ needs some explanation. If a person or family left the village, perhaps to pursue work, the village for which they had settlement would provide them with a certificate, so that if for any reason they became chargeable through illness or disability, their village of settlement would take them back and provide for them.

Likewise if a person came to Woodborough and then became chargeable the Overseers of the Poor in Woodborough could send him or her or the family back to their place of settlement after issuing a Removal Order to the Overseers of the Poor of their original parish.

Settlement Certificates had to be signed by a Justice of the Peace as well as the Overseers of the Poor and often Churchwardens.

One example is William Rose, his wife and child, and John Cutts, his wife and daughter. William Rose married his wife Frances Hardstaffe on 1st May 1704 and their son John was born less than three weeks later on 17th and was baptised at Woodborough church on 11th June. They decided to move to Calverton and the Woodborough Overseers let the Calverton Overseers have a Settlement Certificate to say that if they became chargeable to Calverton parish, Woodborough would have them back.

A Removal Order of 1834 refers to Hannah Booth, whose husband Thomas is absent, and her four children, John 7, William 5, Hannah 3 and Thomas 1. It orders the Overseers of Mansfield, to remove and convey the family back to Mansfield presumably they had become chargeable to Woodborough Parish when husband Thomas absconded.

Protectionism: Protectionism is not new burial in wool was brought in to protect the English wool trade. This was enforced by two Acts of Parliament, the first in 1667 and the second, to enforce it more rigidly, in 1678. The Acts said that no burial was to take place in which the body was wrapped in shirt, shift, sheet or shroud containing any flax, hemp, linen, silk, gold or silver, other than cloth of sheep’s wool.

There was a penalty of £5 on the estate of the deceased for burial in anything other than wool and it was no good stipulating that they were to be buried in any other material as anyone connected with the burial, presumably priest, family, mourners, churchwardens etc. could all be fined £5 each (a lot of money in the 1600’s).

Although the law eventually fell into disuse, it was not finally repealed until 1814. Burials in wool must have occurred in Woodborough, they are specified in some Parish Registers, but burial records in Woodborough are very brief and there is no mention of them.

Plague: The number of burials each year in the Parish Register show not only the population, but also identify years or periods when there was above normal mortality. The word plague was then used for any illness, either bubonic plague or pneumonic plague and what would now be called flu, and typhus and smallpox. Plague would now be an epidemic or pandemic. As the Parish Registers had not been instituted at the time of the Black Death in 1348/9 and its subsequent outbreaks, we cannot know how our village fared, although an indication may be the unfinished blocks of stone in the church at the springs of the aisle arches.

In the years 1603/4 plague was severe in London, and locally at East Bridgford, Holme Pierrepont, Nottingham and Newark. Woodborough too suffered with thirteen deaths in 1603 when the average for the village was 3 to 5. There were high numbers of deaths in the years 1611/12, 1669-1671, 1681/2, 1694, 1728 and 1762-4. In the 3 year period 1669-71, thirty nine people died out of a population of about 250 that is more than one in every 7. In the 3-year period from 1762-4, 42 people were buried out of a population of about 305, about one in 7. However the highest number of deaths here in a two-year period was 34 in the years 1616/17 when according to a recognised formula it could have been due to bubonic plague. With 34 dying out of a population of about 230 that is about one in 7 or 8. The village in 1616/17 must have been devastated, with motherless or fatherless families and maybe a number of orphans.

Woodborough never suffered to the extent that East Stoke on the Fosse Way, near Newark did. In their Parish Register in 1646 there are seven consecutive pages of deaths from the plague after which was written, ‘Here died the town of East Stoke, of eight score and ten persons whereof seven score and nineteen died’. In other words, out of 170 inhabitants 159 died, only 11 surviving the plague. In East Bridgford there were 90 deaths in 1637.

Why did Woodborough escape lightly when places such as East Stoke and East Bridgford were so badly affected?

- Woodborough was not on a main road or direct route between towns. This would mean fewer travellers and wagons passing through that could have been infected or carrying infected goods.

- The River Trent acted as a barrier from travellers journeying North from London up the Fosse Way. There were only fords, (Shelford and East Bridgford), and ferries, between the bridges at Nottingham and Newark.

- Plague often followed food shortages when people would be more susceptible to infection. Woodborough people would probably have enough land and orchard round their homesteads and stock to see them through the winter.

- Overcrowding would have assisted the spread of infection. The citizens of Nottingham confined by town walls and crowded buildings would have been more prone to infection.

- The main occupation of Woodborough’s inhabitants would have been agriculture, working on their strips of land in the Open Fields, and leading an open air life and being more isolated would have made them more resistant to infection.

Occupations: People’s occupations were rarely mentioned in the early Parish Registers although from local wills and inventories for Woodborough it is clear that there were yeoman farmers, husbandmen, cottagers and labourers with a sprinkling of tradesmen such as framework knitters, websters (weavers), carpenters, butchers, blacksmiths, dyers, maltsters and cordwainers (shoemakers and repairers).

In the burial records there is a yeoman, 7 husbandmen, 8 cottagers and 2 labourers. In the period 1637/8 the baptism records show one gentleman, one yeoman, two husbandmen, five labourers and a mason, (one of the dynasty by the name of Sellers). Of the eight described as cottagers in 1616-1620, inventories of their goods at the time of death show one as a labourer, one as a blacksmith and one as a weaver, giving the impression that tradesmen such as blacksmiths and weavers also depended on their smallholdings surrounding their cottages for food and sustenance.

From 1741, with Maurice Pugh as curate, and up to 1785, occupations are given at baptism, marriage and burial.

An analysis for the occupations for the heads of family at baptisms in those years are as follows:- 1 vicar, 1 schoolmaster, 4 millers, 10 shoemakers 5 of whom were members of family groups, 5 wheelwrights, 1 basket maker, 38 labourers, 1 shopkeeper/grocer, 2 soap boilers and a tallow chandler, 2 weavers, 27 framework knitters, 27 farmers, 1 butcher, 2 brickmakers, 4 blacksmiths, 4 tailors and 5 carpenters.

Child Mortality: It is only when Maurice Pugh arrived as curate in 1740 that satisfactory information on child mortality can be accurately obtained. He not only gave the mother’s and father’s Christian name at each baptism but also the father’s occupation and his occupation when his wife or children were buried.

However in the case of the Sleight family, there was only one Sleight family in the village, although they were before Maurice Pugh’s time. Ellen had 11 children in 16 years, of whom six survived, but she seemed determined that one of the girls should be named Ellen after her. Many parents at that time did this. They buried two Ellen’s and the third Ellen was born in 1702, the year the family’s name disappeared from the Registers so she may have survived. Their two girls named Margaret also died and of the two named William one died and the other lived until at least the age of three. In 1699 John, the father is classed as a pauper when William the second was baptised.

As an example of Maurice Pugh’s work we find the following entry – James son of Samuel and Millicent Morley, frame worker, baptised 4 January 1746/7. The Morleys like the Sleights were in-comers, presumably moving into the village framework knitting community, and the first reference to them is the burial of their daughter Rebeccah in 1744. We can’t tell how many children they had in total as many of them appear only in the burials and must have been born before the family came to Woodborough, namely Rebeccah, Joseph, Hannah, Samuel and Elizabeth. Those that were baptised in Woodborough were James, Millicent, John, Sarah and Jane. Of the 10 children we know about, either through baptisms and burials, only John survived. Millicent, the mother herself, died in 1758 having buried nine children in her short stay of about 14-15 years in Woodborough, probably worn out and with a broken heart.

Thomas Donnelly was an interesting character. He too, was a stockinger and came from Arnold. He married Hannah in 1766 and they had two children, Hannah, named after her mother in 1768 and a son Mark in 1772, but later in that year Hannah, the mother, died. Thomas then had an affair with Ann Rimmington the following year and she had an illegitimate child by him. The next year he married Elizabeth Terry and in the next ten years Elizabeth presented Thomas with eight more children. Three out of the four girls died and were all buried in a 3-week period in March 1785.

It was not only the children of labourers and stockingers who failed to survive. William and Mary Bainbridge of the Upper Hall (Woodborough Hall) had either 11 or 12 children, the only one to survive to adulthood being Elizabeth of Fromerty Feast fame and a considerable philanthropist with her generous donation to the Nottingham General Hospital.

Unusual information with the Parish Registers: Parish Registers often include additional information. Notes were often made on the flyleaves or endpapers. Terriers or lists of goods belonging to the church and the charges, tithes etc. may also be found with the Registers.

There are also Royal Briefs which were supposedly to raise money for good causes, but the money is reputed to have been used to supplement the Royal coffers. These Briefs were made with increasing frequency until eventually the public refused to subscribe to them. A Brief, issued in 1660, reads as follows:- On September 23rd. 1660 he (the Minister) collected at the Parish Church and among the inhabitants of Woodborough for and towards the relief of the distressed inhabitants of Willenhall, in the County of Staffordshire being commended hither by the King’s Majesty’s Letters Patents under Court Seal for and towards the loss by fire the sum of 4 shillings and 10 pence – Witness John Allott, Minister and James Jebb and Henry Moorelaw [Morley]. Churchwardens.

It is doubtful whether there ever was a fire at Willenhall and with no newspapers, radio or television the Woodborough inhabitants would never have been able to prove or disprove it.

One item was a personal note by Maurice Pugh saying that a baptism record was so poorly written in 1716 on a damaged page in the Register that he had re-written it in 1742. Incidentally the particular baptism was that of Elizabeth Bainbridge, referred to earlier, which suggests that she was about 82 when she died. There are also notes in the sale of the medieval church window glass, on the re-hanging of the bells, and of the Date Stone and Tower Cross on the 1878 school and who laid them.

Acknowledgement:

- Revised talk by Peter Saunders 24th August 2010

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Life in Woodborough 1538-1810 - The Parish Registers

Parish Registers are not just lists of names but show the joys and sadness, hopes and fears and tragedies of local people and are a source of information on the life of the times.

They were instituted by Archbishop Cromwell under Henry VIII in 1538 who ordered that the incumbent, in the case of Woodborough, the Curate, had to write every Christening, marriage and burial in a book or register in the presence of one or both churchwardens. But as the entries were usually made on loose sheets of parchment which were often lost, in 1603 new regulations were made for a parchment book to be used and kept in a chest with three locks, the minister and churchwardens to each have a key so that all three had to be present for the chest to be opened.

Woodborough baptisms are recorded from 14th November 1547, then a gap from 1554/5 until 1575 and intermittent gaps during the Commonwealth period. Since then they have continued without gaps to the present day. The marriages start on 28th January 1573/4 and the burials start on 4th May 1572, with 34 years lost. With all dates before 1752 the year began on 25th March and dates from 1st January to 25th March are recorded as 1612/13.

Who wrote the Parish Register? The vicar or curate usually, because apart from the gentry and a very few parishioners they were the only ones who could read and write in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. William the Conqueror and his wife Matilda were both illiterate.

When the Parish Registers were originally written the vicar had to supply the Bishop with a copy within twelve months of any entry. These are known as Bishop’s Transcripts and are also available on microfiche at the Nottinghamshire Archives. The Bishop’s Transcripts for Woodborough are poor with long gaps but they do sometimes contain additional names or occupations which can be helpful to a researcher.

Our Parish Registers give us information about the important families living in the three manors and help to confirm the periods they were in occupation. Not always, because a family had to have a baptism, marriage or burial before they were entered in the Parish Register but it at least gives us an approximate date of residence. The important personages are usually denoted by the title, Esquire, Gentleman or Mister – ordinary village inhabitants were just given their Christian and surnames. The important ladies were usually given the title of mistress, but occasionally gentlewoman.

In the burials it is usually mentioned if a woman was a widow and occasionally the term single woman, the words spinster and bachelor were only used for marriages e.g.

- Baptisms

Mary, daughter of Henry Strelley, gent (1549)

John, son of Mr Henry Chaworth and Mistress Mary Chaworth (1625)

- Marriages

Robert Howes, gent and Jane Strelley, gentlewoman (1577)

Mr Lawrence Byrne and Mistress Martha Foster (1716)

- Burials

Mistress Catherine, the wife of Mr John Wood, Esquire (1633)

Jane Bould, wife of John Bould, gentleman (1615)

Titles were not always strictly adhered to; it often depended on the view of the curate. There are a very few examples, usually concerning the gentry, where the information concerning a marriage or a burial is in Latin.

Names: Although one would expect curates to be literate, some were not. They didn’t all live in the village and would not always know how surnames were spelt and names might have been spelt differently if they had moved from one curacy to another. In the 16th to 19th centuries the majority of the inhabitants of the village could neither read nor write, were not even able to write their own name. Spelling of names depended on the literacy or imagination of a curate or vicar.

In Woodborough registers the name Sheppard has at least 15 variations between 1584 and 1660, and Alvey has 8 variations between 1596 and 1670. Alice was a very common Christian name and is spelt in at least 8 different ways between 1547 and 1656. If the curate was not familiar with the person concerned he would spell their name phonetically as it was spoken by them leading to some peculiar variations.

In a period of about 5½ years round about 1660 the mothers’ names were given at baptisms. Out of 43 entries were Mary 10, Elizabeth 9, Ann 4 and 2 each for Sara, Martha and Catherine. Round about 1715 (50 years later), out of 34 entries, 17 of the mothers were named Elizabeth, and 9 were called Mary, only 3 were called Anne. But 40 years later out of 32 entries the number of Anne’s had risen to 11, Elizabeth was down to 8, Mary 5 and there were two each of Sarah’s and Martha’s.

| Navigate this site |

| 001 Timeline |

| 100 - 114 St Swithuns Church - Index |

| 115 - 121 Churchyard & Cemetery - Index |

| 122 - 128 Methodist Church - Index |

| 129 - 131 Baptist Chapel - Index |

| 132 - 132.4 Institute - Index |

| 129 - A History of the Chapel |

| 130 - Baptist Chapel School (Lilly's School) |

| 131 - Baptist Chapel internment |

| 132 - The Institute from 1826 |

| 132.1 Institute Minutes |

| 132.2 Iinstitute Deeds 1895 |

| 132.3 Institute Deeds 1950 |

| 132.4 Institute letters and bills |

| 134 - 138 Woodborough Hall - Index |

| 139 - 142 The Manor House Index |

| 143 - Nether Hall |

| 139 - Middle Manor from 1066 |

| 140 - The Wood Family |

| 141 - Manor Farm & Stables |

| 142 - Robert Howett & Mundens Hall |

| 200 - Buckland by Peter Saunders |

| 201 - Buckland - Introduction & Obituary |

| 202 - Buckland Title & Preface |

| 203 - Buckland Chapter List & Summaries of Content |

| 224 - 19th Century Woodborough |

| 225 - Community Study 1967 |

| 226 - Community Study 1974 |

| 227 - Community Study 1990 |

| 400 - 402 Drains & Dykes - Index |

| 403 - 412 Flooding - Index |

| 413 - 420 Woodlands - Index |

| 421 - 437 Enclosure 1795 - Index |

| 440 - 451 Land Misc - Index |

| 400 - Introduction |

| 401 - Woodborough Dykes at Enclosure 1795 |

| 402 - A Study of Land Drainage & Farming Practices |

| People A to H 600+ |

| People L to W 629 |

| 640 - Sundry deaths |

| 650 - Bish Family |

| 651 - Ward Family |

| 652 - Alveys of Woodborough |

| 653 - Alvey marriages |

| 654 - Alvey Burials |

| 800 - Footpaths Introduction |

| 801 - Lapwing Trail |

| 802 - WI Trail |